by Shaun Chamberlin | Jul 11, 2008 | All Posts, Climate Change, Cultural stories, Favourite posts, Philosophy

Those of you who know me personally will be aware that the indescribable exhilaration of physical movement to music (more commonly termed 'dancing') is my greatest release and joy.

Over the past couple of weeks I have been much enjoying the latest issue of Resurgence magazine, which focuses on the theme 'Music for transformation'.

I have learnt, to my delight, that one of the founders of quantum mechanics, Werner Heisenberg, told his students that they should see the world as made of music, not of matter (by which, as far as I understand it, he meant to emphasise that reality is process, not form).

But in particular, a section of Mark Kidel's article Conversation & Crossroads set me tingling, and ultimately led me to consider how climate change challenges the very basis of Western thought. He writes:

"Some of the most powerful - and healing - forms of music combine strict 'ways' of doing things with free expression and the possibilities of interpretation or improvisation... Wisdom and experience have suggested, in every corner of the world, that excessive self-expression is self-defeating and just as destructive as an over-zealous observance of rules and regulations. There is a need for a middle way which balances 'hot' and 'cool: the release of deep emotion with the articulacy and sophistication of formal aesthetic structures.

Rock music, which has always been about partying and letting go and the realm of the Dionysiac, has fostered excess. This is in large part a 'return of the repressed' as the psychoanalytical tradition would put it; a reaction against the tight-arsed pleasure-denying credo of Protestantism, the dominant religious philosophy of the two main cultures, British and North American, that generated rock out of a complex marriage of black and white musical traditions.

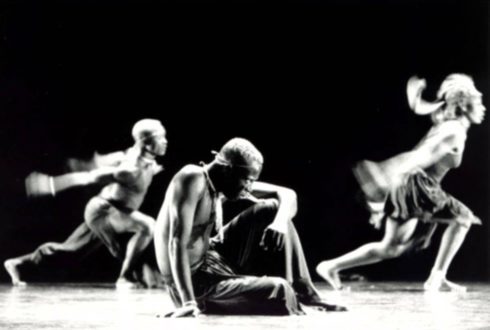

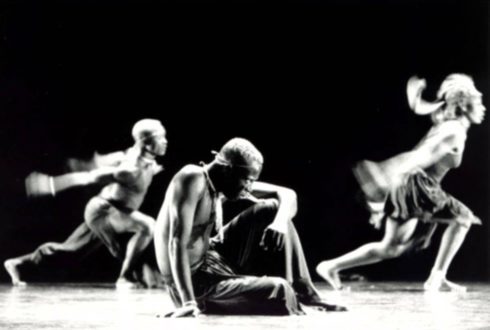

Whereas the enjoyment of pleasure was never frowned upon in the African context, it was set within a deeply rooted sense of ethical and aesthetic 'right behaviour' (as well as a strongly hierarchical community structure which held potential excess in check, and understood, in a highly sophisticated way, the need to balance creative self-expression with collective interaction and mutual support). In the African and African-American context, the dancer who goes into trance is always being controlled in some sense by a divinity or spirits, so there is an element of ritual theatre which contains the fragility of the individual ego. Similarly, at celebrations, no dancer hogs the floor for longer than a minute or two, reaching a brief climax, but not prolonging the transcendent thrill of near-ecstatic movement and expression beyond what is in some way 'safe' or acceptable in terms of strictly personal as opposed to collective expression."

This I find fascinating on a number of levels. Firstly, with direct reference to my own experience of dancing, I immediately recognise the distinction between the relief of cathartic individual expression and the wonder of contributing to, and subsuming oneself to, coordinated collective communication in the language of movement.

But what I had never appreciated before was the way in which a community can hold an artist safe while he or she explores the wilder reaches of individual expression. As Kidel goes on to argue, the absence of this protective tradition around Western rock music can clearly be seen in the likes of Jimi Hendrix and Jim Morrison who, in the context of a culture entranced by individualism, found their lives overwhelmed and consumed by the awesome powers unrestrained artistic expression can unleash.

But these ideas also have a wider application. Rock music has merely reflected Western philosophy and culture in its deification of the individual. When existentialism announced that 'existence precedes essence' - that we simply exist, and that any meaning we might then attribute to this 'blank slate' existence is solely created by ourselves and our own choices - we assumed that the 'we' in question must be our individual selves.

Our culture moves further and further away from any sense of the collective, let alone concepts like oneness with Nature, or with all of creation, or even (Science forbid) God.

This I find fascinating on a number of levels. Firstly, with direct reference to my own experience of dancing, I immediately recognise the distinction between the relief of cathartic individual expression and the wonder of contributing to, and subsuming oneself to, coordinated collective communication in the language of movement.

But what I had never appreciated before was the way in which a community can hold an artist safe while he or she explores the wilder reaches of individual expression. As Kidel goes on to argue, the absence of this protective tradition around Western rock music can clearly be seen in the likes of Jimi Hendrix and Jim Morrison who, in the context of a culture entranced by individualism, found their lives overwhelmed and consumed by the awesome powers unrestrained artistic expression can unleash.

But these ideas also have a wider application. Rock music has merely reflected Western philosophy and culture in its deification of the individual. When existentialism announced that 'existence precedes essence' - that we simply exist, and that any meaning we might then attribute to this 'blank slate' existence is solely created by ourselves and our own choices - we assumed that the 'we' in question must be our individual selves.

Our culture moves further and further away from any sense of the collective, let alone concepts like oneness with Nature, or with all of creation, or even (Science forbid) God.

And it is this philosophy of individualist existentialism - deeply embedded in our culture - that leads to the pervasive story that while some might find their meaning and fulfilment in trying to assure the future of endangered species, or disadvantaged humans, or even life itself, others may equally find theirs in greed, gluttony and destructiveness. For the true believer there is no contradiction here because there is no underlying meaning to seek - only individual constructs.

Within the tenets of Western philosophy it appears a logically unassailable position - if everything is fundamentally meaningless and the freedom of the individual is simply self-evident, what possible reason could there be to cease doing whatever I may fancy?

There seem to me to be two key answers to this question. The first is consequences. What I fancy now may not produce what I fancy tomorrow. If I choose to attach meaning or desirability to a reliable electricity supply, or food supply, then there are certain things I should really pay attention to.

And it is this philosophy of individualist existentialism - deeply embedded in our culture - that leads to the pervasive story that while some might find their meaning and fulfilment in trying to assure the future of endangered species, or disadvantaged humans, or even life itself, others may equally find theirs in greed, gluttony and destructiveness. For the true believer there is no contradiction here because there is no underlying meaning to seek - only individual constructs.

Within the tenets of Western philosophy it appears a logically unassailable position - if everything is fundamentally meaningless and the freedom of the individual is simply self-evident, what possible reason could there be to cease doing whatever I may fancy?

There seem to me to be two key answers to this question. The first is consequences. What I fancy now may not produce what I fancy tomorrow. If I choose to attach meaning or desirability to a reliable electricity supply, or food supply, then there are certain things I should really pay attention to.

But the second is empathy. While we may feel less empathy with beings more different or distant from ourselves, few of us would claim to feel no empathy at all. There is perhaps a sliding scale from total individualism to the sense of oneness with everything which is described in many of the Eastern mystical traditions, as well as among earlier representatives of the Abrahamic religions like Christianity. It is no coincidence that we tend to find individualists despoiling our common environment, and those at the holistic end of the scale defending it.

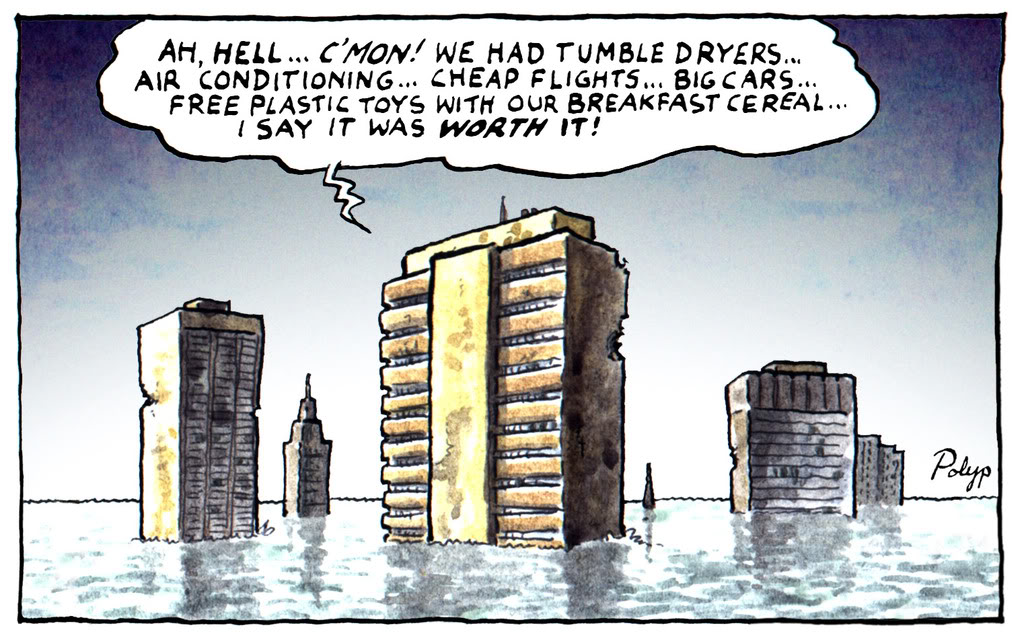

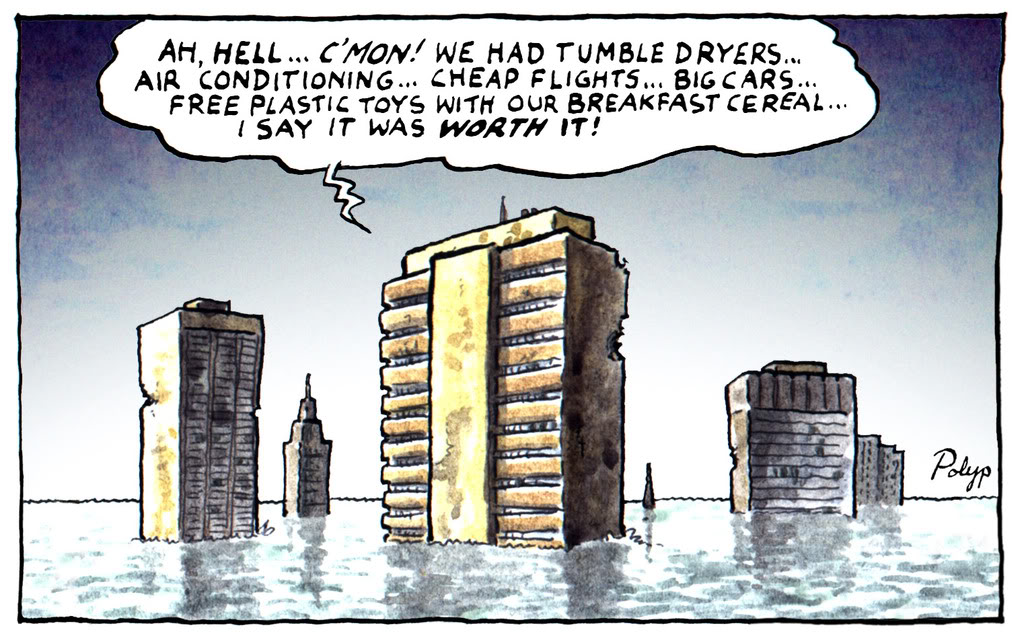

Existentialist individualism argues that one's position on this scale is a fundamentally meaningless personal decision. Our innate sense of empathy might whisper otherwise, but our scientific understanding of collective consequences like climate change forces us to recognise that even if individual freedom is our sole aim, we still have to change course, as the consequences of our actions will seriously curtail the future choices facing both ourself and the rest of life on Earth.

Viewed from this perspective, climate change represents the death of passive individualism as a coherent philosophy. If we don't realise that soon it will also bring the deaths of all the coherent philosophers!

So when Kidel speaks of the highly sophisticated understanding African cultures have of "the need to balance creative self-expression with collective interaction and mutual support", he is not just talking about a better way to dance, he is talking about the very wisdom we need to chart a sustainable future for life on Earth.

But the second is empathy. While we may feel less empathy with beings more different or distant from ourselves, few of us would claim to feel no empathy at all. There is perhaps a sliding scale from total individualism to the sense of oneness with everything which is described in many of the Eastern mystical traditions, as well as among earlier representatives of the Abrahamic religions like Christianity. It is no coincidence that we tend to find individualists despoiling our common environment, and those at the holistic end of the scale defending it.

Existentialist individualism argues that one's position on this scale is a fundamentally meaningless personal decision. Our innate sense of empathy might whisper otherwise, but our scientific understanding of collective consequences like climate change forces us to recognise that even if individual freedom is our sole aim, we still have to change course, as the consequences of our actions will seriously curtail the future choices facing both ourself and the rest of life on Earth.

Viewed from this perspective, climate change represents the death of passive individualism as a coherent philosophy. If we don't realise that soon it will also bring the deaths of all the coherent philosophers!

So when Kidel speaks of the highly sophisticated understanding African cultures have of "the need to balance creative self-expression with collective interaction and mutual support", he is not just talking about a better way to dance, he is talking about the very wisdom we need to chart a sustainable future for life on Earth.

by Shaun Chamberlin | Jun 29, 2008 | All Posts, Climate Change, Cultural stories, Favourite posts, Peak Oil, Philosophy, Reviews and recommendations, TEQs (Tradable Energy Quotas), Transition Movement

As George Carlin once said, "they call it the American dream because you have to be asleep to believe in it".

At the risk of this blog becoming 'review corner', that seems the perfect introduction to the book I just finished reading - Dmitry Orlov's brilliantly enjoyable Reinventing Collapse. This is a true work of dark optimism, with a fair dash of dark humour to boot.

In it, Orlov draws on his experiences of the collapse of the Soviet Union to explore the future American residents like him are likely to face as the effects of the USA's disastrous economic, energy and foreign policies take hold.

Orlov highlights that economic collapse is not, in fact, the unthinkable end of the world, but rather simply a new set of historical circumstances within which to exist. This is a critically important and inherently dark subject, yet the book is suffused with subtle humour, to the extent that at times you are not quite sure when Orlov is serious and when he's joking. The answer, invariably, is both.

This deep humour is an apt way to stimulate further thought in the reader, and after the initial laughter I regularly found myself drawn into a contemplation that led me to Orlov's insights laying beneath.

One subtext particularly intrigued me. While Orlov argues that the collapse of the US economy is inevitable (I would agree), and will surely be extremely difficult for most of those living through it, various asides implied to me that it could be considered in some respects desirable.

This interests me in the context of the desperate urgency of the global climate change situation. As Dr. James Hansen chillingly put it in his recent paper, it is simply becoming a question of whether "humanity wishes to preserve a planet similar to that on which civilization developed and to which life on Earth is adapted". On his reading of the science (and I trust him) we now have less than seven years to decide.

Bearing these stakes in mind, it is interesting to note that Chris Vernon of The Oil Drum quotes the statistic that Russia's carbon emissions fell 31% in the 5 years from the end of the Soviet Union in 1991. Ignoring for a moment all the other effects of that economic collapse, and considering that the weight of evidence tends to suggest that a 'great turning' of the global paradigm may not be likely to take place in time, I am led to ponder whether economic collapse is actually what we should be hoping for - does it represent our best bet for reducing emissions sufficiently quickly to retain a habitable climate on our planet?

I have written before about my belief that while climate change and peak oil represent the greatest direct threat facing humanity today, they are really only symptoms of a deeper problem. Humanity’s obsession with growth means that if we could wish away the excess CO2 in our atmosphere and generate unlimited oil we would still quickly find our unsustainable way of life pressing up against the next environmental limit, be it food shortages, air pollution, species extinctions or whatever.

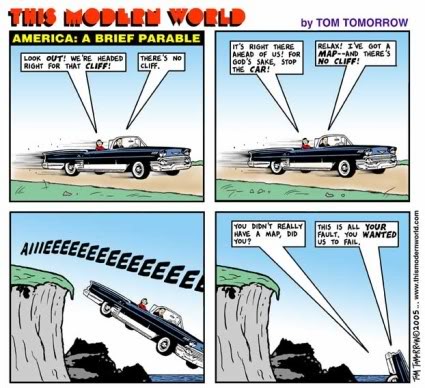

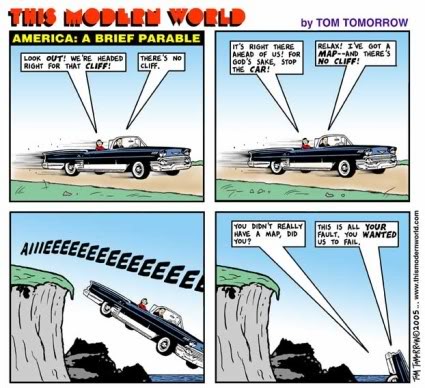

And in turn this growth obsession is a symptom of the underlying cultural stories and philosophies we use to make sense of our lives and find meaning. Our cultural stories define us and strongly impact our behaviours. An example of a dominant story in our present culture is that of “progress” - the story that we currently live in one of the most advanced civilisations the world has ever known, and that we are advancing further and faster all the time. The definition of 'advancement' is vague – though tied in with concepts like scientific and technological progress – but the story is powerfully held. And if we hold to this cultural story then 'business as usual' is an attractive prospect – a continuation of this astonishing advancement. Similarly the cultural story that “fundamental change is impossible” makes it seem inevitable.

Yet even UK Prime Minister Gordon Brown admitted last week that,

“The fact is that a low carbon society will not emerge from thinking of business as usual”

The problem with stories comes when they shape our thinking in ways that do not reflect reality. The evidence might support the view that this 'advanced' culture is not making us happy and is rapidly destroying our environment's ability to support us, it might show that dramatic change is both common and inevitable, but dominant cultural stories are powerful magics, and those who challenge them tend to meet resistance and even ridicule.

Nonetheless, my work now focuses on changing these dominant cultural stories - and thus changing our patterns of thought and behaviour - as I see this as the key to equipping our society to deal with the pressing challenges of climate change and peak oil. TEQs, the Transition movement and the various other initiatives listed on my links page (as well as this blog of course!) seem to me to provide the best possibilities for starting to shift our cultural paradigm.

But perhaps this effort is too little too late? And perhaps by trying to move our society a little closer to long-term sustainability we are in fact just prolonging its existence, and thus prolonging its ability to pump emissions into our atmosphere...

I have written before about my belief that while climate change and peak oil represent the greatest direct threat facing humanity today, they are really only symptoms of a deeper problem. Humanity’s obsession with growth means that if we could wish away the excess CO2 in our atmosphere and generate unlimited oil we would still quickly find our unsustainable way of life pressing up against the next environmental limit, be it food shortages, air pollution, species extinctions or whatever.

And in turn this growth obsession is a symptom of the underlying cultural stories and philosophies we use to make sense of our lives and find meaning. Our cultural stories define us and strongly impact our behaviours. An example of a dominant story in our present culture is that of “progress” - the story that we currently live in one of the most advanced civilisations the world has ever known, and that we are advancing further and faster all the time. The definition of 'advancement' is vague – though tied in with concepts like scientific and technological progress – but the story is powerfully held. And if we hold to this cultural story then 'business as usual' is an attractive prospect – a continuation of this astonishing advancement. Similarly the cultural story that “fundamental change is impossible” makes it seem inevitable.

Yet even UK Prime Minister Gordon Brown admitted last week that,

“The fact is that a low carbon society will not emerge from thinking of business as usual”

The problem with stories comes when they shape our thinking in ways that do not reflect reality. The evidence might support the view that this 'advanced' culture is not making us happy and is rapidly destroying our environment's ability to support us, it might show that dramatic change is both common and inevitable, but dominant cultural stories are powerful magics, and those who challenge them tend to meet resistance and even ridicule.

Nonetheless, my work now focuses on changing these dominant cultural stories - and thus changing our patterns of thought and behaviour - as I see this as the key to equipping our society to deal with the pressing challenges of climate change and peak oil. TEQs, the Transition movement and the various other initiatives listed on my links page (as well as this blog of course!) seem to me to provide the best possibilities for starting to shift our cultural paradigm.

But perhaps this effort is too little too late? And perhaps by trying to move our society a little closer to long-term sustainability we are in fact just prolonging its existence, and thus prolonging its ability to pump emissions into our atmosphere...

Does our need for a relatively benign climate logically dictate that we should be striving to bring about economic collapse sooner rather than later?

It is an interesting question, and one that we may need to revisit, but my answer is still no. The human suffering caused by such a sudden collapse is overwhelming, and I believe that kinder options are still open to us.

Personally, I believe we still have a chance. I still believe, firstly, that a long-term future for humanity is possible, and secondly that we have a shot at developing a society that responds in a humane way to the crises we face. And I will fight for that possibility for as long as I believe in it and still see a chance that it exists, even as the window of possibility continues to shrink.

When it comes down to it, at the deepest level it doesn’t really matter to me whether or not it is probable that we succeed. As Tom Atlee has written,

“Probabilities are abstractions. Possibilities are the stuff of life, visions to act upon, doors to walk through.”

I will walk through the doors that inspire me.

Of course, there is a side of me that asks "but what if we do reach a time when the evidence is clear - when there is no longer any chance of avoiding the devastation of our climate". If we were on the Titanic and we had already hit the iceberg there would be little point in trying to patch the hole as the waters raged in - so what then?

Well, the trite answer would be that there's quite enough to worry about now without concerning myself with that. The more interesting answer comes back to what we believe life is fundamentally about, but that will have to wait for a future post.

Oh, and just what does Dmitry Orlov suggest in terms of personally adapting to an economic collapse? Well, you'll have to read his book for that!

Does our need for a relatively benign climate logically dictate that we should be striving to bring about economic collapse sooner rather than later?

It is an interesting question, and one that we may need to revisit, but my answer is still no. The human suffering caused by such a sudden collapse is overwhelming, and I believe that kinder options are still open to us.

Personally, I believe we still have a chance. I still believe, firstly, that a long-term future for humanity is possible, and secondly that we have a shot at developing a society that responds in a humane way to the crises we face. And I will fight for that possibility for as long as I believe in it and still see a chance that it exists, even as the window of possibility continues to shrink.

When it comes down to it, at the deepest level it doesn’t really matter to me whether or not it is probable that we succeed. As Tom Atlee has written,

“Probabilities are abstractions. Possibilities are the stuff of life, visions to act upon, doors to walk through.”

I will walk through the doors that inspire me.

Of course, there is a side of me that asks "but what if we do reach a time when the evidence is clear - when there is no longer any chance of avoiding the devastation of our climate". If we were on the Titanic and we had already hit the iceberg there would be little point in trying to patch the hole as the waters raged in - so what then?

Well, the trite answer would be that there's quite enough to worry about now without concerning myself with that. The more interesting answer comes back to what we believe life is fundamentally about, but that will have to wait for a future post.

Oh, and just what does Dmitry Orlov suggest in terms of personally adapting to an economic collapse? Well, you'll have to read his book for that!

by Shaun Chamberlin | Jun 22, 2008 | All Posts, Favourite posts, Peak Oil, Politics

I find myself wondering if our current political system (like so much else in our modern culture) might be partially a product of the bonanza of abundant cheap energy we have been enjoying for the last century or two. Have we been so comfortable that the pressure has been off for our decision makers?

Now I am certainly no student of politics, and my musings should be taken with that proviso, but it has always seemed a little strange that there is such a widespread perception of our politicians as incompetent and immoral, and yet they continue to be entrusted with the ultimate decision-making role for our society. There is widespread disinterest among the young people I know, and perhaps part of the reason is that people have 'learnt' that it really doesn't matter how ineffective politicians may be - there still always seems to be water in the tap and food on the table, so surely they must be doing something right?

Equally it hasn't seemed to matter much to many people whether we had a Conservative or a Labour government - we just sort of swing back and forth based on something like national mood. According to political commentators, the reasons for these electoral shifts seem to be sentiments like "they've had long enough" or, more recently, "finances are a bit tight".

Yet it's an odd thing to swing to the current opposition because of our economic difficulties. If we really believed there was much of a difference between the two wouldn't we make a decision and stick with it? Does anyone truly believe that the UK budget would be vastly better off had the Conservatives been in power for the past few years?

The depletion of the North Sea (oil production there peaked at around 2.9m barrels/day in 1999 and is now at around half those levels) is marginally impacted by political decisions, but is essentially a geological fact, and importing just 0.2m barrels per day at the current price of around $135/barrel adds $10 billion a year to our trade deficit. Could the Conservatives have turned back time on depletion, resolved the global credit crunch, or prevented the upsurge in the globally traded price of food, or of oil for that matter?

I would venture that either party would have done just about as bad a job as the other. It's not about whether Gordon Brown or David Cameron is in the hotseat, there is something much more fundamental going on than that. As Voltaire said, "men argue, Nature acts".

Worryingly, there seem to be only two recognised political parties in the UK who understand the kind of future we are facing - the Green Party and the British National Party, both of whom show a firm awareness of the reality of energy resource depletion. Needless to say they advocate very different responses.

As Rob Hopkins pointed out some time ago, an interesting aspect of peak oil is that everyone seems to see its potential to usher in the kind of world they want to see. While the Greens see the potential to move to a more ecologically-friendly way of life in response to the need for lower energy consumption, the BNP recognise that in times of hardship extreme right wing groups have traditionally done very well.

The reality is that there are many possible futures, but we get to choose which of them come to pass. To put it another way, we will get the future we deserve.

This is why when I speak to my friends who refuse to vote on the basis of their disgust with the major parties I urge them to vote Green. There are alternatives, and it is hard to sustain the argument that a Green vote is a wasted vote when the alternative you are considering is not to vote at all.

I would venture that either party would have done just about as bad a job as the other. It's not about whether Gordon Brown or David Cameron is in the hotseat, there is something much more fundamental going on than that. As Voltaire said, "men argue, Nature acts".

Worryingly, there seem to be only two recognised political parties in the UK who understand the kind of future we are facing - the Green Party and the British National Party, both of whom show a firm awareness of the reality of energy resource depletion. Needless to say they advocate very different responses.

As Rob Hopkins pointed out some time ago, an interesting aspect of peak oil is that everyone seems to see its potential to usher in the kind of world they want to see. While the Greens see the potential to move to a more ecologically-friendly way of life in response to the need for lower energy consumption, the BNP recognise that in times of hardship extreme right wing groups have traditionally done very well.

The reality is that there are many possible futures, but we get to choose which of them come to pass. To put it another way, we will get the future we deserve.

This is why when I speak to my friends who refuse to vote on the basis of their disgust with the major parties I urge them to vote Green. There are alternatives, and it is hard to sustain the argument that a Green vote is a wasted vote when the alternative you are considering is not to vote at all.

by Shaun Chamberlin | May 19, 2008 | All Posts, Climate Change, Peak Oil, Politics

As I mentioned in my earlier post, last week I met Polly Higgins, The Lazy Environmentalist. She specialises in CSP, and informed me that we may now be seeing serious political movement towards an EU-MENA supergrid bringing CSP-generated electricity to Europe from the...

I have

I have  Does our need for a relatively benign climate logically dictate that we should be striving to bring about economic collapse sooner rather than later?

It is an interesting question, and one that we may need to revisit, but my answer is still no. The human suffering caused by such a sudden collapse is overwhelming, and I believe that kinder options are still open to us.

Personally, I believe we still have a chance. I still believe, firstly, that a long-term future for humanity is possible, and secondly that we have a shot at developing a society that responds in a humane way to the crises we face. And I will fight for that possibility for as long as I believe in it and still see a chance that it exists, even as the window of possibility continues to shrink.

When it comes down to it, at the deepest level it doesn’t really matter to me whether or not it is probable that we succeed. As Tom Atlee has written,

“Probabilities are abstractions. Possibilities are the stuff of life, visions to act upon, doors to walk through.”

I will walk through the doors that inspire me.

Of course, there is a side of me that asks "but what if we do reach a time when the evidence is clear - when there is no longer any chance of avoiding the devastation of our climate". If we were on the Titanic and we had already hit the iceberg there would be little point in trying to patch the hole as the waters raged in - so what then?

Well, the trite answer would be that there's quite enough to worry about now without concerning myself with that. The more interesting answer comes back to what we believe life is fundamentally about, but that will have to wait for a future post.

Oh, and just what does Dmitry Orlov suggest in terms of personally adapting to an economic collapse? Well, you'll have to

Does our need for a relatively benign climate logically dictate that we should be striving to bring about economic collapse sooner rather than later?

It is an interesting question, and one that we may need to revisit, but my answer is still no. The human suffering caused by such a sudden collapse is overwhelming, and I believe that kinder options are still open to us.

Personally, I believe we still have a chance. I still believe, firstly, that a long-term future for humanity is possible, and secondly that we have a shot at developing a society that responds in a humane way to the crises we face. And I will fight for that possibility for as long as I believe in it and still see a chance that it exists, even as the window of possibility continues to shrink.

When it comes down to it, at the deepest level it doesn’t really matter to me whether or not it is probable that we succeed. As Tom Atlee has written,

“Probabilities are abstractions. Possibilities are the stuff of life, visions to act upon, doors to walk through.”

I will walk through the doors that inspire me.

Of course, there is a side of me that asks "but what if we do reach a time when the evidence is clear - when there is no longer any chance of avoiding the devastation of our climate". If we were on the Titanic and we had already hit the iceberg there would be little point in trying to patch the hole as the waters raged in - so what then?

Well, the trite answer would be that there's quite enough to worry about now without concerning myself with that. The more interesting answer comes back to what we believe life is fundamentally about, but that will have to wait for a future post.

Oh, and just what does Dmitry Orlov suggest in terms of personally adapting to an economic collapse? Well, you'll have to

I would venture that either party would have done just about as bad a job as the other. It's not about whether Gordon Brown or David Cameron is in the hotseat, there is something much more fundamental going on than that. As Voltaire said, "men argue, Nature acts".

Worryingly, there seem to be only two recognised political parties in the UK who understand the kind of future we are facing - the

I would venture that either party would have done just about as bad a job as the other. It's not about whether Gordon Brown or David Cameron is in the hotseat, there is something much more fundamental going on than that. As Voltaire said, "men argue, Nature acts".

Worryingly, there seem to be only two recognised political parties in the UK who understand the kind of future we are facing - the

Recent Comments