by Shaun Chamberlin | Nov 29, 2016 | All Posts, David Fleming, Lean Logic, Surviving the Future

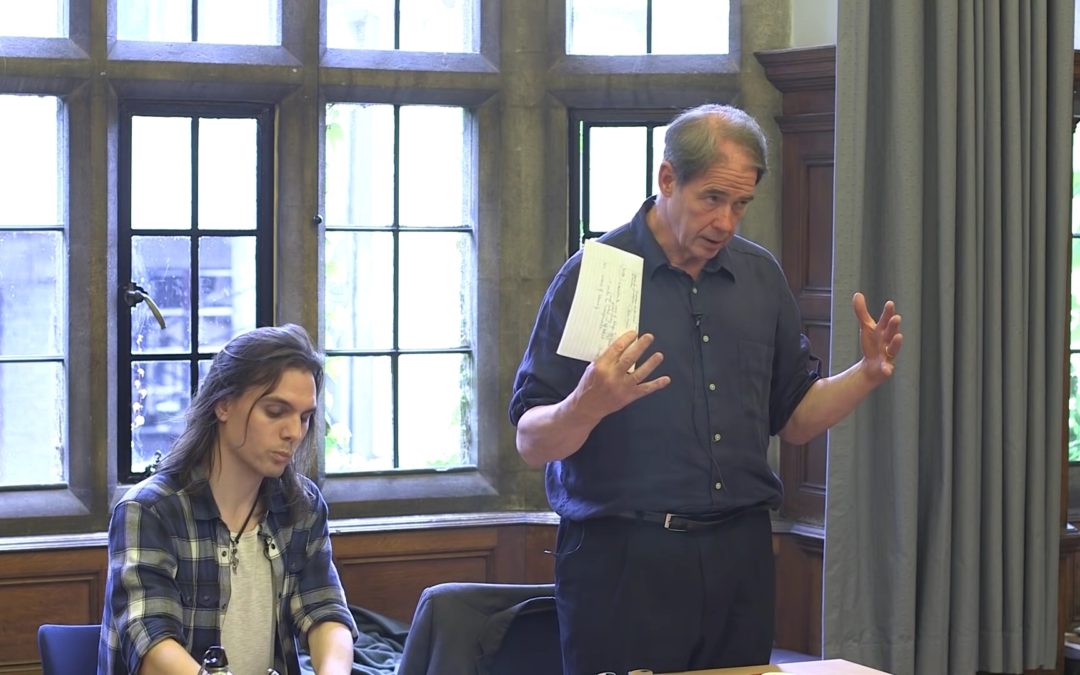

A personal post this, on the sixth anniversary of my dear friend David Fleming’s death. A mournful day, but also one of great satisfaction, as his incredible books finally spread their wings and find the audience his genius always deserved. Ten years on from our...

by Shaun Chamberlin | May 29, 2015 | All Posts, Climate Change, Cultural stories, Economics, Out and about, Politics, TEQs (Tradable Energy Quotas), Transition Movement

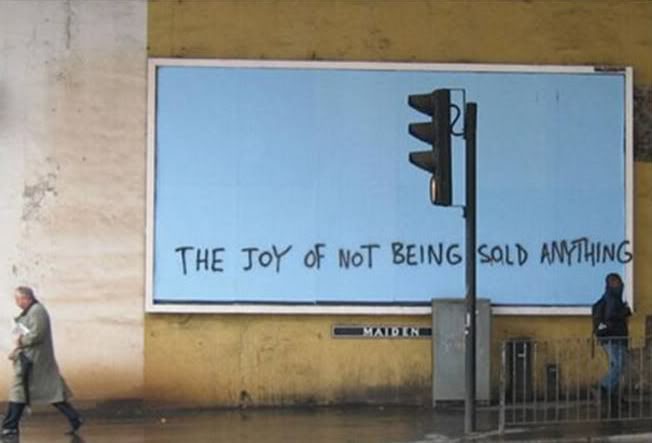

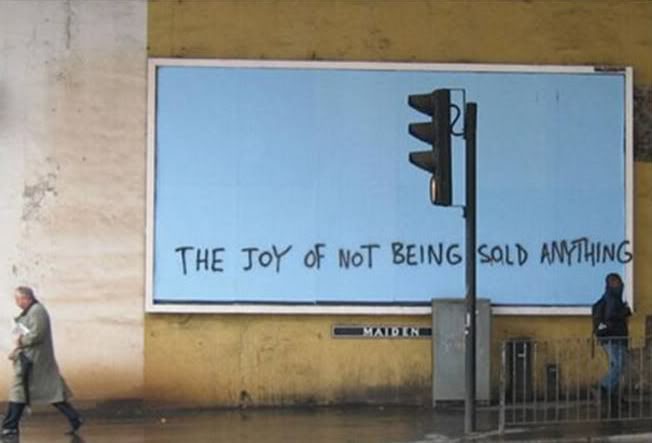

Lately we’ve seen the president of the World Bank and ‘business leaders from the very carbon-intensive industries’ pushing for carbon pricing (taxes or ‘carbon trading’ schemes). This is intended to demonstrate their deep change of heart...

by Shaun Chamberlin | May 19, 2014 | All Posts, Cultural stories, Economics, Philosophy, Transition Movement

This post was originally written by me as a guest post for Rob Hopkins’ Transition Culture blog, but I have kindly given myself permission to reproduce it here ? A response to a recent post by Rob Hopkins ‘The impact of Transition. In numbers.’....

by Shaun Chamberlin | Sep 20, 2012 | All Posts, Cultural stories, Economics, Politics, Reviews and recommendations, TEQs (Tradable Energy Quotas), Transition Movement

Out today from Pluto Press is What We Are Fighting For: A Radical Collective Manifesto – a book to which I was delighted to contribute. My chapter, “The Struggle for Meaning”, wraps up the section on ‘New Economics’ and addresses our...

by Shaun Chamberlin | May 17, 2012 | All Posts, Cultural stories, David Fleming, Economics, Favourite posts, Politics, The Transition Timeline, Transition Movement

Last month I was one of forty or so attendees of the Transition ‘Peak Money’ day. It was a fascinating collection of people, from theorists to activists, and a potent opportunity to reflect on the challenges facing us all as the glaring errors at the heart...

Recent Comments