by Shaun Chamberlin | Jan 20, 2013 | All Posts, Climate Change, Cultural stories, Favourite posts, Featured, Philosophy

When environmentalists argue amongst themselves, whether at some formal debate or late at night over a few drinks, I confidently predict that the argument will go like this.

One will say (in one form or another):

"There's no time to wait for radical change or revolution; the crisis is overwhelmingly urgent, we simply have to act within the frameworks we have now".

by Shaun Chamberlin | May 17, 2012 | All Posts, Cultural stories, David Fleming, Economics, Favourite posts, Politics, The Transition Timeline, Transition Movement

Last month I was one of forty or so attendees of the Transition ‘Peak Money’ day. It was a fascinating collection of people, from theorists to activists, and a potent opportunity to reflect on the challenges facing us all as the glaring errors at the heart...

by Shaun Chamberlin | Dec 21, 2011 | 21st December, All Posts, Cultural stories, Reviews and recommendations

David Buckland, text Amy Balkin, ‘Going to hell on a handcart.’, Ice Art “Untitled, 2010” was written by artist Maria Elvorith for The Future We Deserve, a book project about collaboratively creating the future we deserve, set for publication in January...

by Shaun Chamberlin | Jun 15, 2011 | All Posts, Climate Change, Cultural stories, Favourite posts, Philosophy, Transition Movement

Last night I went to the première screening of an excellent new film called Just Do It. It’s a record of the direct action climate movement — Climate Camp, Plane Stupid et al. — made with the full cooperation of the activists, and it’s worth checking out,...

by Shaun Chamberlin | Jan 23, 2011 | All Posts, Climate Change, Cultural stories, Economics, Peak Oil, Politics, Reviews and recommendations, TEQs (Tradable Energy Quotas), Transition Movement

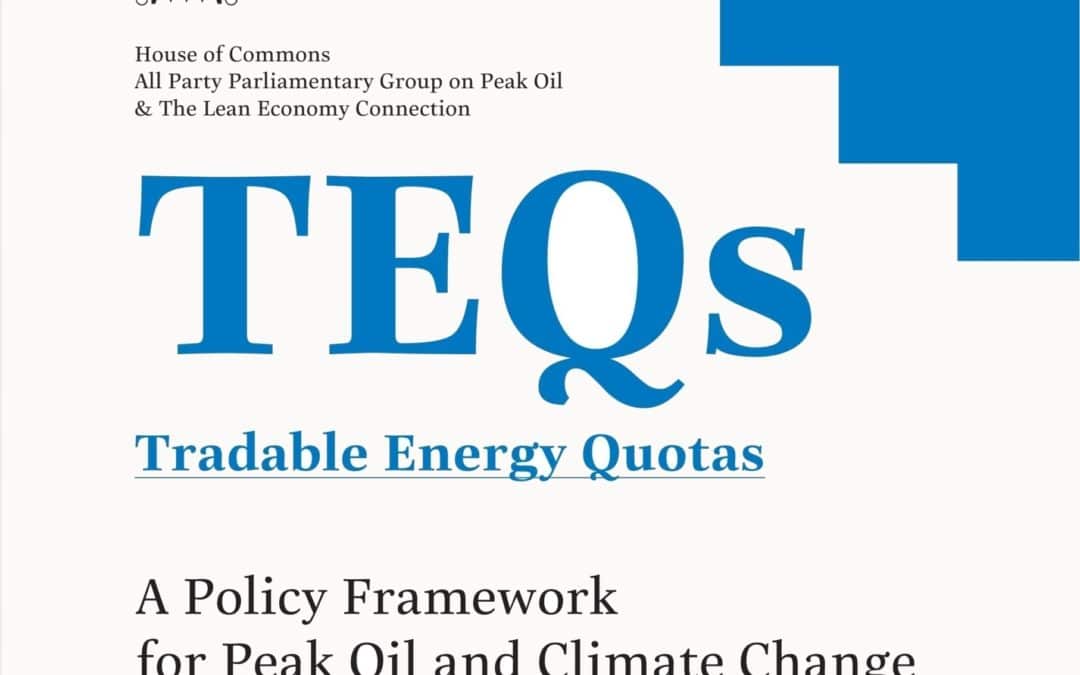

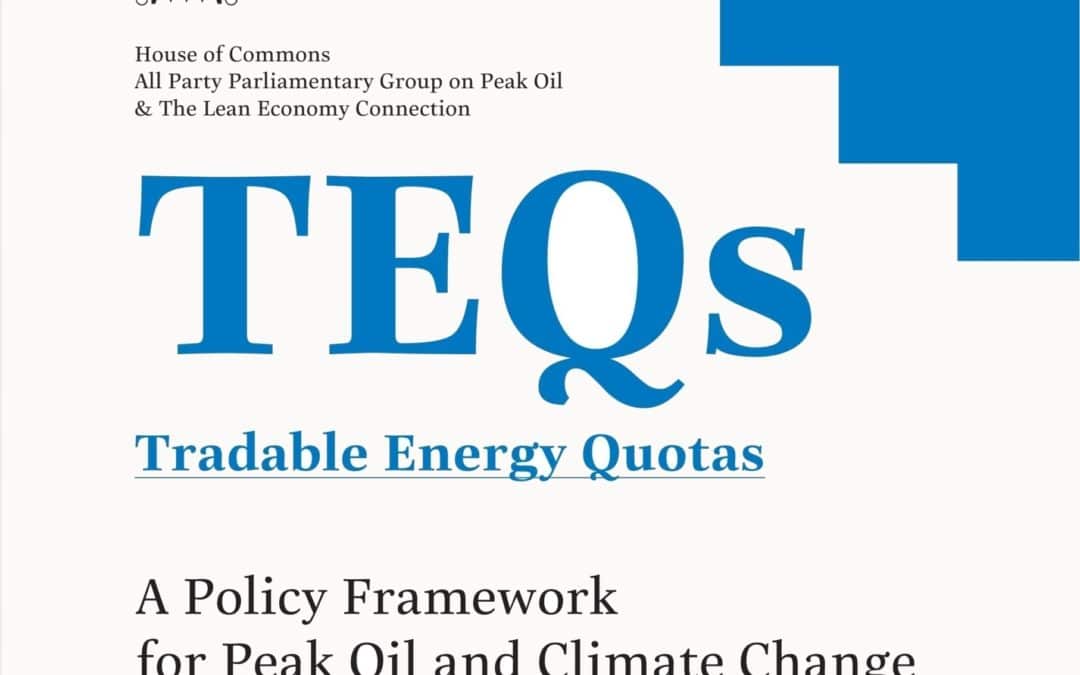

What a week – Tuesday’s launch of the All Party Parliamentary Group on Peak Oil’s report into TEQs was a tremendous success, with excellent media coverage, including Time magazine, The Sunday Times, Bloomberg News, the BBC, the Financial Times and...

Recent Comments