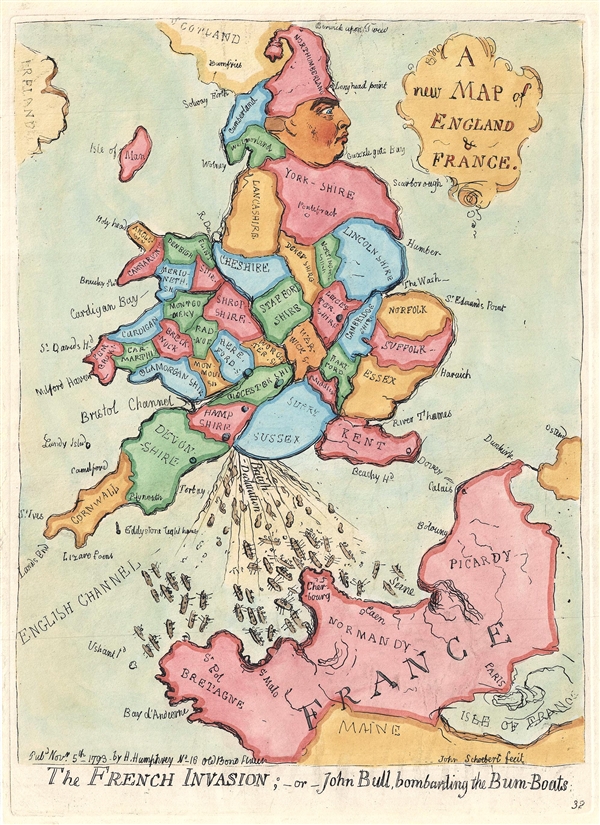

by Shaun Chamberlin | Aug 21, 2016 | All Posts, David Fleming, Economics, Lean Logic, Reviews and recommendations, Surviving the Future, TEQs (Tradable Energy Quotas)

Last week the wonderful Brianne Goodspeed of Chelsea Green Publishing interviewed me on my late mentor David Fleming and the astonishing gift he left to the world.

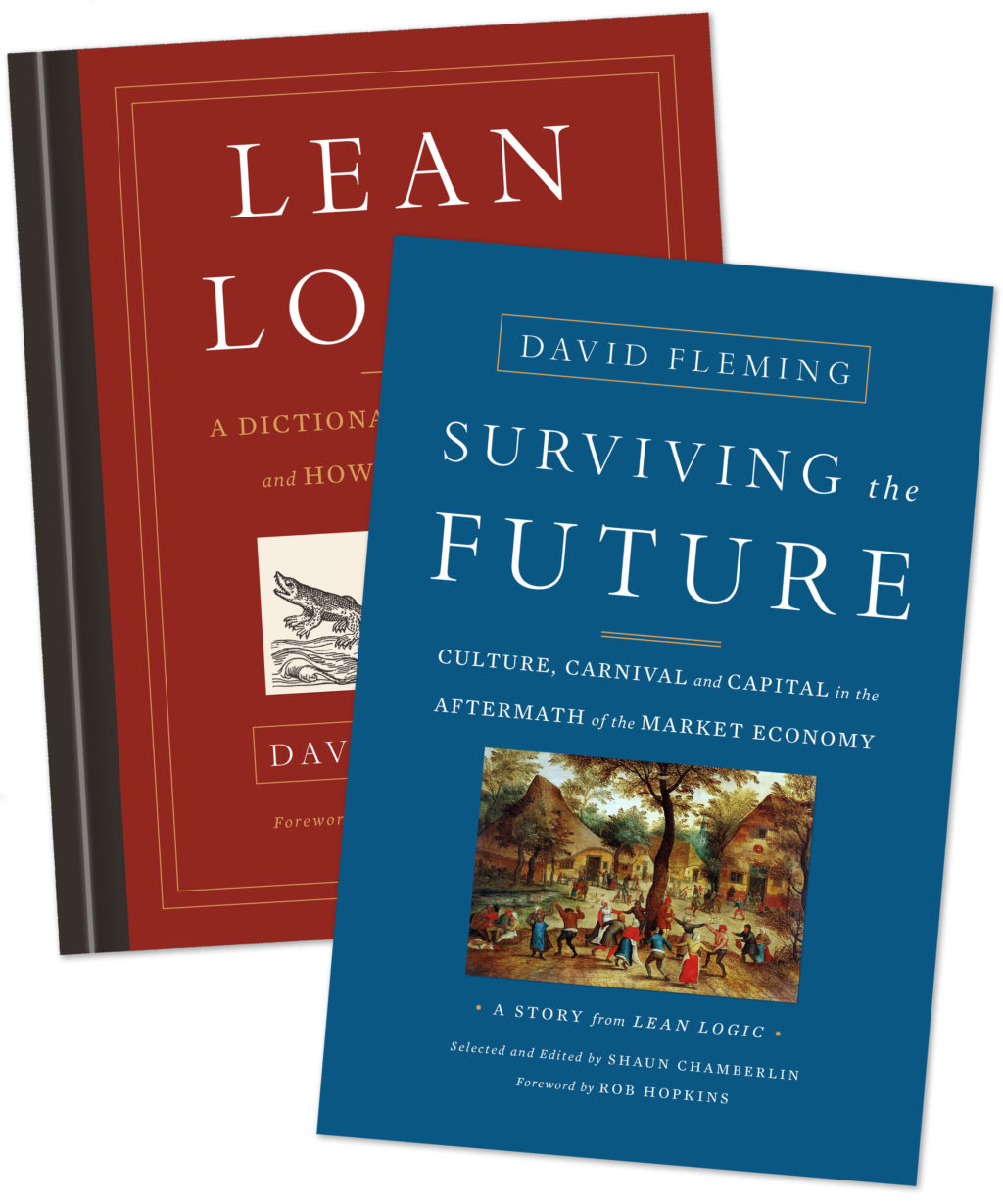

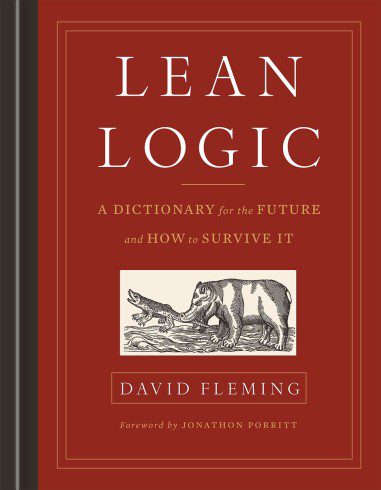

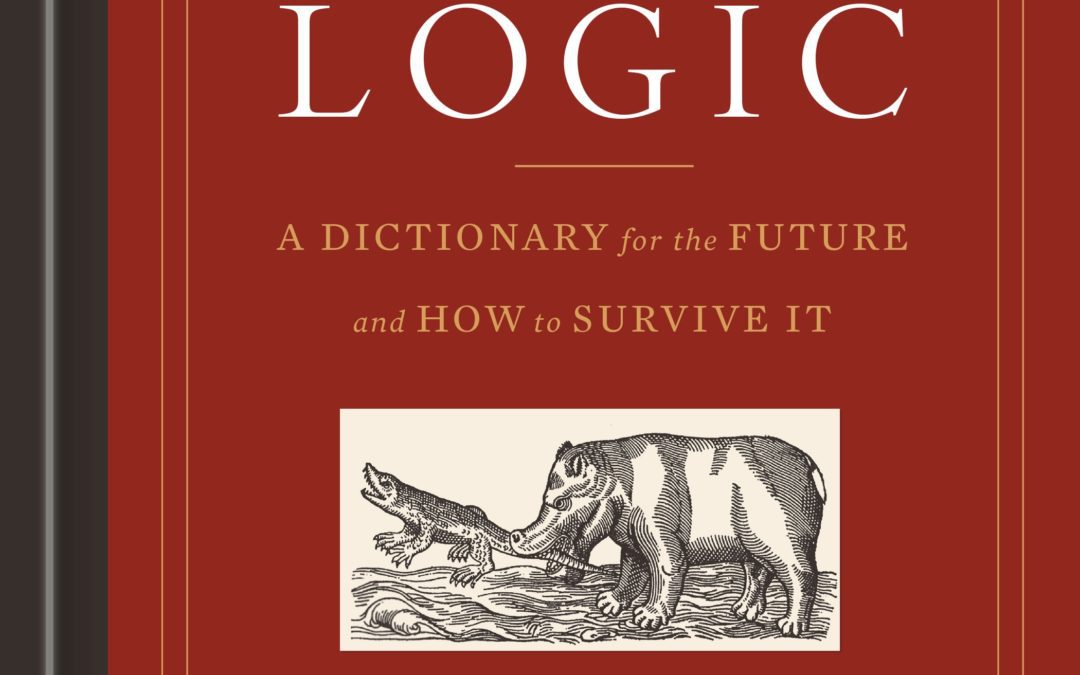

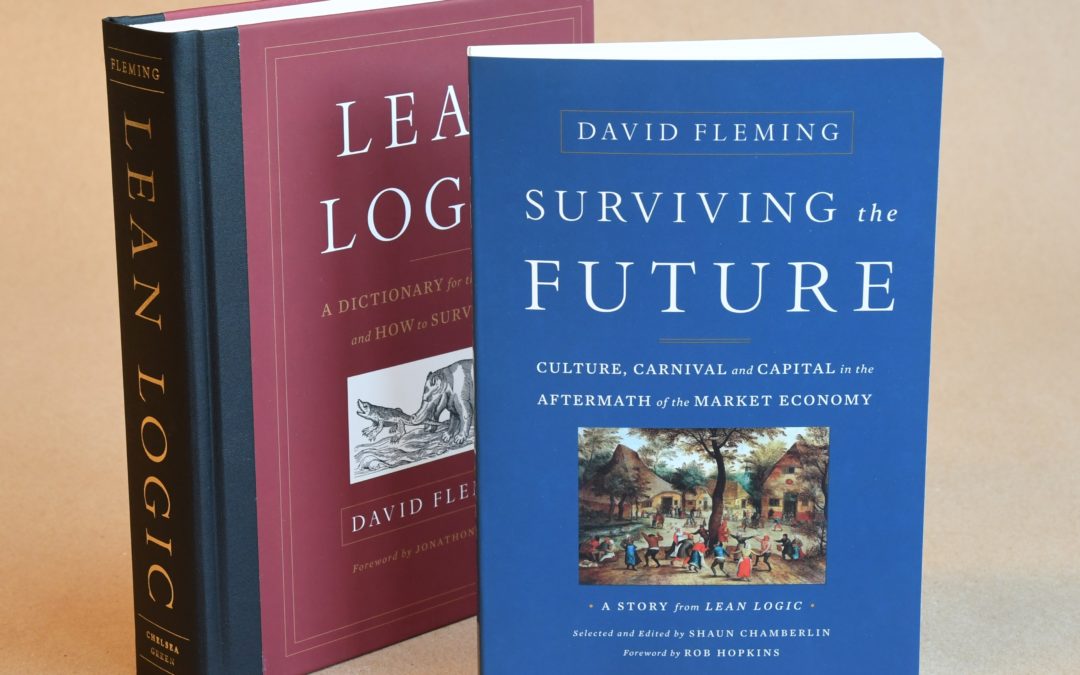

His sudden death in 2010 left behind his great unpublished work—Lean Logic: A Dictionary for the Future and How to Survive It—a masterpiece more than thirty years in the making.

In it, Fleming examines the consequences of an economy that destroys the very foundations—ecological, economic, and cultural—upon which it is built. But his core focus is on what could follow its inevitable demise: his compelling, grounded vision for a cohesive society that provides a satisfying, culturally-rich context for lives well lived, in an economy not reliant on the impossible promise of eternal economic growth. A society worth living in. Worth fighting for. Worth contributing to.

And since his death, I have edited out a paperback version—Surviving the Future: Culture, Carnival and Capital in the Aftermath of the Market Economy—to concisely present his rare insights and uniquely enjoyable writing style in a more conventional read-it-front-to-back format. Chelsea Green are simultaneously launching both on September 8th, but since I have just received my first copies, I believe some bookshops may have them already...

For more about the man, the books, and the hippo, read on!

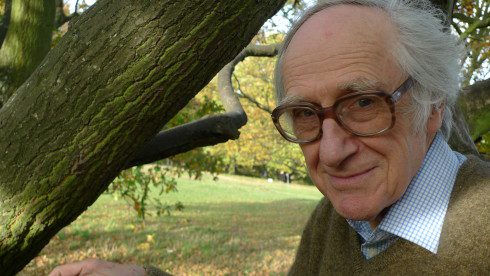

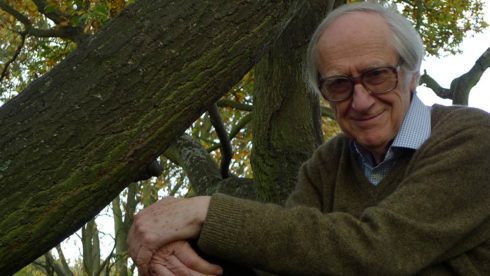

Q: Who was David Fleming?

For me, a life-changer. I first met him ten years ago, when I was struggling to find a way to engage with the great ecological crises of our time, and he showed me how to build a life following my passion. He was teaching at Schumacher College—a sort of elder of the UK green movement who had been involved with the origins of the Green Party here, and of the New Economics Foundation, designed a carbon rationing system under active investigation by the government, and was just in the process of shaping the birth of the Transition movement.

But above all, he was one of the most generous and insightful people I ever met, and conversations with him rank among the most startling and refreshing experiences of my life. I think that really shines through in his writing.

Q: What was David’s involvement with the Transition movement?

Rob Hopkins once told me—rather too humbly, I’d say—that creating Transition was simply a process of taking Heinberg’s insights into peak oil, Holmgren on permaculture and Fleming on community resilience, rolling them together and making the whole thing comprehensible! In his foreword to Surviving the Future, Rob talks a lot more about David’s important influence and direct involvement, and his role as a great friend of the early Transition groups in London. At Transition Town Kingston, which I cofounded, the talk David gave us on carnival remains legendary!

Q: Lean Logic is described as his life's work. How so? And why did he choose a dictionary format as its conveyance?

Ha—no one who knew him would ask such a question! I rarely saw him without the manuscript in close reach, and perpetually scribbling, editing and re-editing. I’m reliably informed that the same was true for the preceding couple of decades. During interesting conversations, he would often proclaim that the insights gleaned would lead to a rewrite of the relevant section, and he meant it!

We used to joke that I would end up publishing the book posthumously, and of course that’s exactly how it turned out. In truth, after putting so much of his heart and soul into it, I think he was a little afraid to release it; partly because his perfectionism said that it was never quite finished, but perhaps more because it would have broken his heart if nobody read it. Fortunately, early indications are that it’s proving very popular indeed.

The dictionary format is, I think, a unique expression of a unique mind. One of the most striking things about conversations with David was the utterly unexpected connections he would draw, suddenly quoting poetry by heart to break the rational mindset, or enlightening a conversation about complexity with a reference to antelopes, or bringing The Wind in the Willows into an earnest chat about local identity. The dictionary format translates that onto the page, with an unexpected asterisk leading the mystified reader from “Frankness” to “Carnival”, or from “Local Wisdom” to “Insult”, with that intrigue often resolving into laughter shortly after!

For the reader, it also overcomes one of the frustrations that can often exist when encountering a writer who marshals such a range of influences. Rather than opening each entry with a long introduction giving all the ideas he wants to draw upon, Fleming can get straight to the heart of what he wants to say, leaving the option with the reader as to whether they want to follow up the links for more context.

It also gives a wonderfully free ‘choose your own adventure’ feel to exploring the book as you pursue the threads of your fascination. And being divided into convenient chunks makes it ideal for dipping in and out, even if it can be tantalisingly tricky to put down!

Q: What is its relationship to Surviving the Future?

Well, of course David never had a sniff that Surviving the Future would exist! Lean Logic was the legacy he left to the world, but there’s no getting away from the fact that it’s a very big book and a very unconventional one. Nothing wrong with that, but the first potential posthumous publishers I spoke with were worried that people might find it a bit daunting.

Never afraid of a good daunt, myself and a couple of David’s friends took this as an invitation to produce something a bit more accessible, which ended up, a few years later, emerging as the manuscript for Surviving the Future. Essentially we picked one of those potential paths through Lean Logic, and then I edited that narrative into a conventional read-it-front-to-back paperback.

For me the core of David’s work—the part I find most unique and inspiring, and the part that everything else in Lean Logic hangs off—is his revolutionary economics. Drawing on his education in modern history, he explains that economics before the market economy was rooted wholeheartedly in culture; and that the ongoing loss of community and culture that so many bemoan today is because they have become merely decorative—an optional extra—rather than the essence of our economic lives. And his work shows how much more beautiful life could be—not to mention how much more able to be sustained—if we rediscover and rebuild that.

I’m sure others will disagree that this is the core of Lean Logic—David’s own introduction lists 14 key questions that the book addresses, of which this is only one—but that is probably the key thread that I pulled out for the paperback. I won’t pretend it wasn’t painful to leave out treasures such as “Nanotechnology”, “Spirit”, “Humility”, “Climate Change”, “Imagination”, “Anarchism” and “Resilience”, but that’s what the full dictionary’s for!

Overall, I couldn’t be happier with the result as a sort of friendly gateway to Fleming’s masterpiece; not least because once Chelsea Green Publishing saw it, they didn’t hesitate to sign up the books!

Q: What was your relationship to David?

As I mentioned, we first met at Schumacher College back in 2006. He was teaching on a two-week course there called “Life After Oil”, alongside Richard Heinberg, Rob Hopkins, Michael Meacher and others. At that point I was deeply concerned about environmental issues such as climate change and oil depletion, and looking for a meaningful way to engage with that, and Fleming’s talk really energised me. When he mentioned that he felt he was somewhat lacking in allies, I took my chance and somewhat cheekily suggested that I had some ideas for editing his recent “Energy and the Common Purpose” booklet that I felt could improve it.

An English gentleman through and through, he was a little taken back by the impertinence of this young man, and I well remember him looking me down and up before eventually suggesting that I should join him for lunch that day. After that, he extended the same invitation the following day, and at the end of that second lunch he proffered his card, with an invitation to visit his Hampstead flat when I returned to London. Incidentally, on that same course my fellow student Ben Brangwyn met Rob Hopkins, and they went off and founded the Transition Network together.

As it turned out, David very much liked what I did with his booklet, and from then on we were pretty well inseparable, working closely together on various projects until his sudden death in 2010. He placed only one firm condition on the arrangement—ever a fan of the informal, he insisted that we share a drink in the local pub at least once a week, to avoid things getting too stuffy!

That suited me just fine, and I will treasure those drinks and wide-ranging conversations for the rest of my life. He was a storehouse of fascination as well as a remarkably attentive listener, and for me it was incredible to have a mentor who seemed to know everyone—if I mentioned some book or article I had read, his usual response was along the lines of “oh, I’ll give the author a call, we’ll have coffee”!

For someone who up ‘til then had largely been researching things alone on the internet, it was a godsend. And from his point of view it was a delight to find a firm ally with remarkably similar interests and perspective. The partnership worked beautifully, and we often edited each other’s work, which fortunately left me with a strong “internal David” to consult for my work on these books.

Curiously, I saw David on the London Underground last week—well, ok, someone who looked and moved exactly like him from where I was standing. I take it that he’d stopped by the mortal plane to check out his new books! ‘Seeing’ him brought back to me quite viscerally just what a pleasure it was to be in his company and brought to mind the words of a fellow Transitioner remembering his first meeting with David—“I was left thinking that this was the sort of man I would aspire to be.” Quite.

Q: One of the wonderful things about Fleming’s work is that while, yes, he deals with peak oil and climate change and all the difficulties that go with living beyond our planetary means, one of the things he mourns the loss of most in our current globalized market economy is the space for play, and carnival, and culture. And he envisions a future when that will once again have an important place in our lives. Can you describe his vision?

A few months before he died, David did an interview up an oak tree—don’t ask!—in which he was asked to describe his book . . .

“I think the book is all really about getting on with life and crucially getting on in life in the things that really matter. And what really matters is music . . .

Interviewer: music. . . ?

David: . . . and humour and conversation and painting, the arts, things like that, and having fun, play and farting about and generally enjoying life. That’s what really, really matters, I mean everything else is . . . well, the needle hiss, we used to say in the old days. Gramophone records . . . oh you are probably too young to know that expression anyway [laughing]”

And what becomes ever clearer as you read is that he is by no means advocating turning away from the difficulties you describe and finding distraction in entertainment. Rather he argues convincingly that this rebuilding and enjoying of culture is the only viable basis of a non-ecocidal culture—the only human system that has ever worked. Play is, as he says, what really matters. Unfortunately, these days, the hiss has taken over our lives.

Fleming’s vision is of a culture built around what we love, and entries such as “Carnival” explain beautifully how essential such pleasures are to a healthy society, and how misguided the early stirrings of capitalism were in relentlessly crushing such indiscipline. His definition of wisdom is telling, I think: “Intelligence drenched in culture”.

I will never forget his response when one earnest Transitioner asked what one thing he should do to improve the resilience of his local community: “join the choir”.

Q: David Fleming was, among other things, an economist—a very unorthodox one. And he pioneered a carbon trading system called TEQs (Tradable Energy Quotas) that was taken seriously at the highest level of British government. Can you explain TEQs and where the idea stands now?

Sure, TEQs is basically carbon rationing. That’s an idea that many environmentalists talk about these days, but David was the one who first figured out the practicalities of how it would actually work. And it’s a system based on his great faith in the small-scale, in a diversity of local solutions. As he wrote, “Large-scale problems do not require large-scale solutions—they require small-scale solutions within a large-scale framework.”

So TEQs is the national-scale framework he devised to encourage and harness local-scale solutions like the Transition Towns, and join them up into a guaranteed cap on emissions and a strong sense of national common purpose. It is the missing link that allows the local to address a global challenge like climate change.

And unfortunately it is still missing. As David wrote, “At present, we have a policy-response shaped by sophisticated climate science, brilliant technology and pop behaviourism, based on simple assumptions about carrot-and-stick incentives.”

David first published on TEQs back in 1996, as an alternative to carbon taxation, of which he was a strong critic. By 2004 a Private Member’s Bill was passed by eleven Members of Parliament expressing interest in the TEQs system. This led to extensive research and popular writing into the idea and in 2006 our then-Secretary of State for the Environment, David Miliband, announced a government-funded feasibility study. In 2008, this study reported that TEQs would be progressive, that there were no technical obstacles to implementation and that public acceptability was better than for alternatives such as carbon taxes.

However, future Prime Minister Gordon Brown’s Treasury stomped on the idea, in my opinion because they feared that an effective system to limit carbon emissions might also limit economic growth. Several high-profile MPs and other political figures continued to advocate for the idea— indeed an All-Party Parliamentary Group commissioned David and me to coauthor a report, which came out in early 2011 to international headlines, weeks after his death; and TEQs remains policy for the Green Party here—but in the absence of active government support it has been kicked into the long grass.

Having seen the whole story first-hand, myself and two colleagues published an academic paper on TEQs last year, which is already the most-read paper in the history of the Carbon Management journal. But it seems that the rift between political reality and the physical reality of climate change remains too wide for any policy to bridge at this point.

Q: What would David Fleming’s reaction to Brexit have been?

Hm, a good question, and one I have been pondering myself. It isn’t an area we ever really discussed, but there are certainly clues in his writing; above all in Lean Logic’s entry “Nation”, where he writes that “there is a reduced chance—in a centralised setting such as that being developed by the European Union—of rebuilding a stabilised society from the bottom-up”.

So while I voted to “remain”, just, I suspect David would have voted with the majority. And watching the stunned aftermath of Brexit, I’ve been reflecting on that a lot. Among green lefties there seems to have been a sense that anyone who voted for Brexit must have been either a deluded idiot or a racist, but I think David’s work articulates beautifully the far more positive, reasonable motives that many will have had for their vote—a desire for more accountable control, closer to home; recognition of the economic truth that unlimited movement of both people and capital does indeed drive down wages for the working class; and above all a desire to reclaim a clear identity—something that David describes as “the root condition for rational judgement”. If you don’t know who you are then how can you know what to do?

A nation, after all, is a powerful root for identity, built through long association with a particular place and culture, which many generations have shaped and defended. As David writes, “if defeated, the nation often manages, eventually, to come back into being, with a sense of renewal and justice. It exists in the mind of its people.” And it gives an identifiable meaning to the sense of “we”, to a “national interest”. This, perhaps, is what the European Union was seen to be threatening—our sense of who we are—and why so many rejected it. Of course there are plenty in America who still feel the same way about the United States.

But more than a route to understanding Brexit’s causes, I see Fleming’s work as a progressive, practical vision of what it could look like. If Brexit is the path we are taking, then we need to reclaim it from the xenophobes and racists who see the “Leave” vote as a vindication.

Globalisation and neoliberalism are destroying our collective future, but they have also all-but-destroyed the present for many, as the neofeudalism termed ‘austerity’ continues to bite. The one common factor behind unexpected election results like Brexit, Trump and Corbyn may be desperate rejection of the establishment and the status quo—all the major parties supported “Remain” after all.

It is important to remember that fascists like Mussolini and Hitler didn’t only consolidate power on the basis of lies and fear—they also raised wages, addressed unemployment and greatly improved working conditions. So if we are to avoid the slow drift into real fascism, we need to present an alternative politico-economic vision that can restore identity, pride and economic well-being. We need to tell a beautiful story of how we will make the future better for the desperate, rather than a fearful one.

This is the story that Fleming’s books tell, and what inspired me to devote my past few years to bringing them to publication. His startling seven-point protocol for an economics based in trust, loyalty and local diversity is, quite simply, the only realistic, grounded alternative I have seen to a future I have no desire to live through.

Q: Although he was eager to see the end of the market economy as we know it, David Fleming also had considerable fondness for it. Can you explain why?

I’m not sure that fondness is quite the word, but yes, you’re right. Again David said it well himself in that interview with Henrik Dahle up a tree on Hampstead Heath:

“I am a capitalist and I am a bit of a right winger, to most people’s horror and shock, and I think in many ways the system we have got at the moment is really not a bad system. I think capitalism is a good thing. The only problem with capitalism is that it destroys the planet, and that it’s based on growth. I mean apart from those two little details it’s got a lot to be said in its favour.

. . . It’s not necessarily against a system that it collapses, because most systems do collapse in the end. That’s a part of the wheel of life—systems do collapse. So I’m to some extent slightly inclined to forgive capitalism for being about to collapse. I mean there are lots of fine things, lots of love affairs and the like which have come to a sticky end. On the other hand, it is quite an accusation—quite hard for it to live down—that not only is it based on the ludicrous idea that growth can continue indefinitely, but it’s going to destroy the entire planet with it.”

So he could see both sides: addressing those actively eager to see the collapse of the growth-based economy and the comfort, simplicity and social order that it enables for many, he quoted “War is sweet to those who know it not.” Yet on the other hand he decried the devastation that the market economy has wrought on culture, community and cohesion, and the way that it “has infantilised a grown-up civilisation and is well on the way to destroying it”.

For David there was no point in working to bring down the market economy—that will come quite soon enough, faster than we might wish—so the only approach that makes sense is to rebuild the cultural roots of the ‘informal economy’, the economy on which we will find ourselves utterly reliant again in the aftermath of the collapse.

Q: Fleming was so creative and whimsical and had a great command of English language. Can you give us a few examples of your favourite “Fleming-isms”?

Off the top of my head, one that everyone seems to remember is his succinct reminder to those quick to make accusations of hypocrisy: “If an argument is a good one, dissonant deeds do nothing to contradict it. In fact, the hypocrite may have something to be said for him; it would be worrying if his ideals were not better than the way he lives.”

Then there’s the one that Rob Hopkins never tires of quoting: “Localisation stands, at best, at the limits of practical possibility. But it has the decisive argument in its favour that there will be no alternative.”

And my own personal favourite, skewering the myth of perpetual economic growth: “Every civilisation has had its irrational but reassuring myth. Previous civilisations have used their culture to sing about it and tell stories about it. Ours has used its mathematics to prove it.”

This was just the way he spoke though; the list goes on and on . . .

Q: What is the story of this bizarre hippopotamus woodcut on the cover of Lean Logic?

Well, it was engraved by Conrad Gesner back in 1551, so you’d have to ask him! But in Lean Logic the image’s very inexplicability is sort of the point—as David explains in the “Hippopotamus” entry such magnificent animals stand as an important reminder of the limits to the ability of logic to make sense of things, in the presence of the big facts of nature. A symbolic reminder, then, that our civilisation stands on the brink of some hard lessons in humility.

In that entry he quotes David Hume: “Nature will always maintain her rights, and prevail in the end over any abstract reasoning whatsoever.”

--

Full details of Shaun's extensive tour in support of the books available here.

Latest info on the books, reviews etc, including the audiobook/film versions, available here.

--

Full details of Shaun's extensive tour in support of the books available here.

Latest info on the books, reviews etc, including the audiobook/film versions, available here.

by Shaun Chamberlin | Dec 21, 2015 | All Posts, Climate Change, Economics, Politics, TEQs (Tradable Energy Quotas)

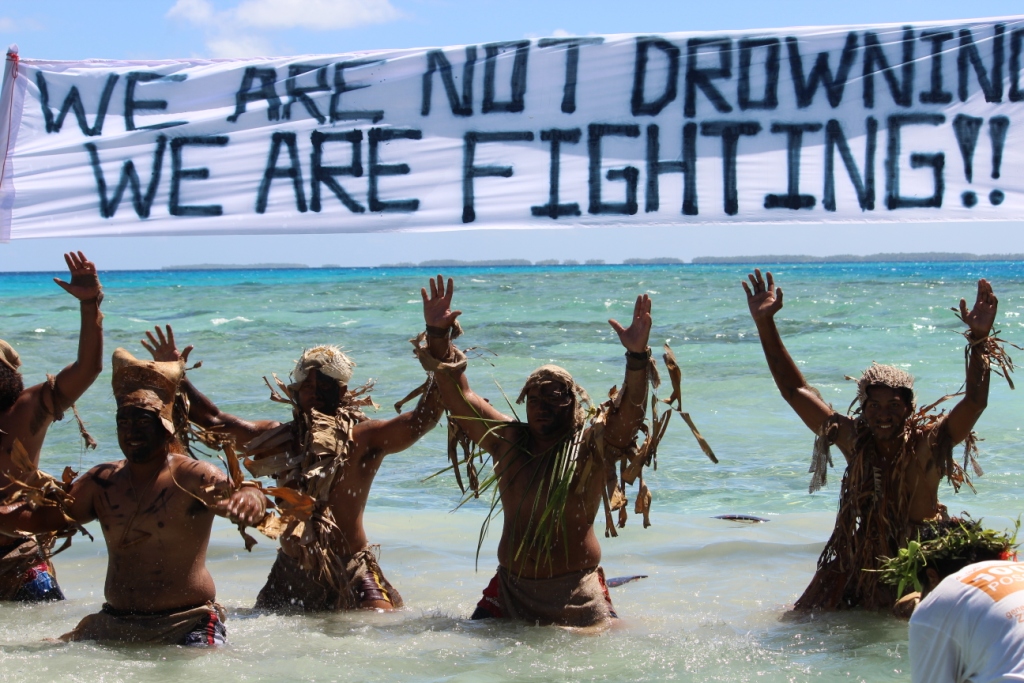

We just sent out our Fleming Policy Centre newsletter, with reflections on the Paris climate summit. Bottom line: it's not good. In the words of the author Naomi Klein, "Our leaders have shown themselves willing to set our world on fire."

Meanwhile, the mainstream media seem to be doing their best to put the world to sleep again. One excitable front-page headline I noticed in The Observer proclaimed:

"World leaders hail Paris climate deal as ‘major leap for mankind’: Almost 200 countries sign historic pledge to hold global temperatures to a maximum rise of 1.5C above pre-industrial levels".

The same article concluded on p9, with a quiet mention that: "there will be no legal obligation for countries to cut emissions".

In truth, the good news is found elsewhere, with the ever-swelling numbers of ordinary people realising that our future is being destroyed in our name. In the print edition of the paper though, one tiny voice of sanity did sneak in to a sidebox, as climate scientist James Hansen commented on the agreement: “It’s a fraud really, a fake”.

But if we are so dismissive of what global politics is producing, then it is perhaps fair to ask what we wish to see instead. Hansen, a long-time hero of mine, argues for Fee & Dividend - a tax on carbon whose revenue is paid out to the population of the nation implementing it. And the recent peer-reviewed paper that I lead-authored on this topic (now the most read in the history of Carbon Management) instead advocates TEQs - a carbon rationing system with free rations for the population of the nation implementing it.

Jim and I have in fact been discussing these alternatives via very occasional emails since I first wrote to him on it in 2008 (and Citizens' Climate Lobby UK opened the same discussion on Facebook earlier this year), but it feels the right time to broaden out the conversation.

My hope is that we can either agree that one approach or the other is preferable or - perhaps more realistically - at least identify the circumstances/aims for which one or the other is preferable, so that we know when to reach for one tool, and when to use the other.

So, below are the similarities and differences between the two approaches, for your delectation and deliberation. I will again be sending the link to Hansen and the Citizens' Climate Lobby for comments, and may edit it based on comments received, especially if any inaccuracies come to light.

So how are they similar?

Let's start with why both TEQs and F&D are excellent ideas that would represent a radical break from the status quo.

Both are ways of ensuring that society finally gets serious about addressing our climate challenge, neither is open to the extensive corporate windfalls that characterise existing 'Cap and Trade' schemes (which have no effective cap, and thus are really just 'Trade' schemes), and both look to protect the poorest in society as energy prices rise to take account of the impact of the carbon therein (although I have a concern that dividends - delivered after energy purchases - may come too late for folk priced out of the fuel they need. TEQs, by contrast, delivers entitlements to energy up front, ahead of time).

Both are also grassroots alternatives to the UN process of which the Paris COP21 summit is the latest expression. Instead of seeking global agreement on a global deal, both TEQs and F&D allow adoption by individual countries or groups of countries. Any countries doing so will necessarily introduce import tariffs alongside, to ensure that their manufacturers are not disadvantaged relative to international competitors (discussed here). And since these tariffs will generate revenue for the 'adopter countries' when they import goods, this will in turn provide a strong incentive for the exporting countries to themselves implement similar policies, so that they can collect this revenue, instead of letting it flow overseas. In this way, effective climate policy could spread around the world, without the necessity for the apparent impossibility of global agreement.

Importantly though, both are also vulnerable to a lack of political ambition. Both require adoption at government level, and thus require defence against being corrupted and compromised by lobbying interests as they move towards implementation. And if F&D was adopted with too low a carbon price, or TEQs was adopted with too high an emissions cap, either could provide merely a useful means to inadequate ends.

Let's start with why both TEQs and F&D are excellent ideas that would represent a radical break from the status quo.

Both are ways of ensuring that society finally gets serious about addressing our climate challenge, neither is open to the extensive corporate windfalls that characterise existing 'Cap and Trade' schemes (which have no effective cap, and thus are really just 'Trade' schemes), and both look to protect the poorest in society as energy prices rise to take account of the impact of the carbon therein (although I have a concern that dividends - delivered after energy purchases - may come too late for folk priced out of the fuel they need. TEQs, by contrast, delivers entitlements to energy up front, ahead of time).

Both are also grassroots alternatives to the UN process of which the Paris COP21 summit is the latest expression. Instead of seeking global agreement on a global deal, both TEQs and F&D allow adoption by individual countries or groups of countries. Any countries doing so will necessarily introduce import tariffs alongside, to ensure that their manufacturers are not disadvantaged relative to international competitors (discussed here). And since these tariffs will generate revenue for the 'adopter countries' when they import goods, this will in turn provide a strong incentive for the exporting countries to themselves implement similar policies, so that they can collect this revenue, instead of letting it flow overseas. In this way, effective climate policy could spread around the world, without the necessity for the apparent impossibility of global agreement.

Importantly though, both are also vulnerable to a lack of political ambition. Both require adoption at government level, and thus require defence against being corrupted and compromised by lobbying interests as they move towards implementation. And if F&D was adopted with too low a carbon price, or TEQs was adopted with too high an emissions cap, either could provide merely a useful means to inadequate ends.

And what are the essential differences?

Now let's look at where they differ. There are two fundamental design decisions here - the choice between a price-based framework and a quantity-based one, and the choice between an 'upstream' framework and a 'downstream' one.

The essential difference between price-based frameworks and quantity-based frameworks, then, is which of two variables is adjusted.

Price-based policy frameworks (e.g. F&D) act to raise the price of carbon-rich purchases in the belief/hope that consequent emissions reductions will be sufficient to avoid climate catastrophe, while quantity-based frameworks (e.g. TEQs) act to place a cap on emissions in the belief/hope that the price rises this is likely to cause will not cause economic catastrophe.

The second difference is between ‘upstream’ and ‘downstream’ approaches. These widely-used terms draw an analogy between the flow of water in a stream and the flow of energy/carbon through an economy.

‘Upstream’ advocates (e.g. F&D) want to regulate the few dozen fuel and energy companies that bring carbon into the economy, arguing that this is cheaper and simpler than addressing the behaviour of tens of millions of ‘downstream’ consumers. 'Downstream' advocates argue that such engagement with the general populace is essential if we are to meet the climate challenge, with TEQs providing a way to deliver that without the need for downstream monitoring.

Now let's look at where they differ. There are two fundamental design decisions here - the choice between a price-based framework and a quantity-based one, and the choice between an 'upstream' framework and a 'downstream' one.

The essential difference between price-based frameworks and quantity-based frameworks, then, is which of two variables is adjusted.

Price-based policy frameworks (e.g. F&D) act to raise the price of carbon-rich purchases in the belief/hope that consequent emissions reductions will be sufficient to avoid climate catastrophe, while quantity-based frameworks (e.g. TEQs) act to place a cap on emissions in the belief/hope that the price rises this is likely to cause will not cause economic catastrophe.

The second difference is between ‘upstream’ and ‘downstream’ approaches. These widely-used terms draw an analogy between the flow of water in a stream and the flow of energy/carbon through an economy.

‘Upstream’ advocates (e.g. F&D) want to regulate the few dozen fuel and energy companies that bring carbon into the economy, arguing that this is cheaper and simpler than addressing the behaviour of tens of millions of ‘downstream’ consumers. 'Downstream' advocates argue that such engagement with the general populace is essential if we are to meet the climate challenge, with TEQs providing a way to deliver that without the need for downstream monitoring.

Tentative conclusions

It is undoubtedly true that current politics favours the price-based and upstream approaches, which present far less of a challenge to today's dominant thinking. Certainly in the U.S. political context, Jim Hansen has argued that TEQs are just too radical an option for the American public to swallow. I am not an expert on the U.S. political scene, so he may well be right.

However, I do worry that a more radical shift in society *is* needed here. There is a rift between political reality and scientific reality, and they must be reconciled. To my mind, upstream price signals are not going to be enough, though a scheme like F&D would certainly be a step closer to sanity than current policy. To really achieve the change required, we will need TEQs.

And since I believe that the economy is fully dependent on a functioning ecology, for me a hard cap on emissions must be primary, and the price of goods and services has to be secondary, which is why I favour a quantity-based approach. I also don’t believe a long-term emissions trajectory can be set effectively through a tax/fee alone.

I do think that Fee & Dividend would be far cheaper and more effective than current carbon policy, but while upstream frameworks are clearly cheaper (and politically easier) to implement, I believe that this is partly because they don't bring about the fundamental changes that are needed in society. Of course it is more straightforward to pass laws that only affect energy suppliers, but Big Energy Companies alone are not going to be able to resolve climate change, even if they wholeheartedly wanted to. They supply what we demand, and this challenge requires that we all engage with the need to change the way we live, work and play.

TEQs, accordingly, is built on the latest work in social psychology, and provides visibility to the intrinsic incentives that exist for businesses, government, communities and individuals to collaborate in working towards the shared long-term desires to retain both a benign climate and secure access to essential energy services.

Upstream schemes can only provide an extrinsic (price) signal to encourage low-carbon behaviour. In the words of the UK Environmental Audit Committee (the UK government’s oversight body on the environment):

It is undoubtedly true that current politics favours the price-based and upstream approaches, which present far less of a challenge to today's dominant thinking. Certainly in the U.S. political context, Jim Hansen has argued that TEQs are just too radical an option for the American public to swallow. I am not an expert on the U.S. political scene, so he may well be right.

However, I do worry that a more radical shift in society *is* needed here. There is a rift between political reality and scientific reality, and they must be reconciled. To my mind, upstream price signals are not going to be enough, though a scheme like F&D would certainly be a step closer to sanity than current policy. To really achieve the change required, we will need TEQs.

And since I believe that the economy is fully dependent on a functioning ecology, for me a hard cap on emissions must be primary, and the price of goods and services has to be secondary, which is why I favour a quantity-based approach. I also don’t believe a long-term emissions trajectory can be set effectively through a tax/fee alone.

I do think that Fee & Dividend would be far cheaper and more effective than current carbon policy, but while upstream frameworks are clearly cheaper (and politically easier) to implement, I believe that this is partly because they don't bring about the fundamental changes that are needed in society. Of course it is more straightforward to pass laws that only affect energy suppliers, but Big Energy Companies alone are not going to be able to resolve climate change, even if they wholeheartedly wanted to. They supply what we demand, and this challenge requires that we all engage with the need to change the way we live, work and play.

TEQs, accordingly, is built on the latest work in social psychology, and provides visibility to the intrinsic incentives that exist for businesses, government, communities and individuals to collaborate in working towards the shared long-term desires to retain both a benign climate and secure access to essential energy services.

Upstream schemes can only provide an extrinsic (price) signal to encourage low-carbon behaviour. In the words of the UK Environmental Audit Committee (the UK government’s oversight body on the environment):

“We remain to be convinced that price signals alone, especially when offset by the [additional income from the dividend], would encourage significant behavioural change comparable with that resulting from a carbon allowance … A meaningful reduction in emissions will only be achieved, and maintained, with significant and urgent behavioural change.”

In summary then, in addition to their shared benefits, I see the relative advantages of the two schemes as:

Fee & Dividend: Cheaper and faster to implement; less challenging to politics/markets; carbon price set by the Department of Energy.

TEQs: Deeper engagement with the whole population based on principles drawn from social psychology; consistent, cohesive integration of a long-term perspective; stimulation of cross-sector collaboration in reducing emissions; a carbon cap set in accordance with climate science.

~~~

As ever, it comes down to that rift between scientific reality and political reality. To my eyes, Fee & Dividend represents the less challenging political path to policy change, and that is certainly attractive. However, while it is tempting to think of adoption of a carbon fee or cap as a solution in itself, the true political challenge is quickly getting and keeping the fee high enough (or cap low enough) to avoid destabilising our climate. Which in turn means the transformation of our society so that it can thrive within such a limit. Without such a fundamental transition to low-carbon living, society (and particularly the poorest) will hurt badly as any effective policy makes high-carbon energy less accessible. Such suffering is both inherently distressing and likely to lead to irresistible political pressure to loosen or abandon any such policy.

Why then does that point me towards TEQs? Well, the full arguments and evidence are set out in the peer-reviewed paper I recently lead-authored. I believe it's worth a look - it has proved popular, perhaps due to the extensive efforts I made to keep it more readable than academia usually manages! But in short, I believe that TEQs is far better placed to support and facilitate the depth of decarbonisation required - and thus defend its long-term political feasibility - than an increase in the price of carbon ever could.

This is because it has been shown to be more popular with the public (due to its fairness and effectiveness); because it most effectively protects the most vulnerable; because it destroys at a stroke the impossible political tension between needing to keep energy prices low and carbon prices high; and because it does not treat all emissions as equal (in recognition that while some are within people's discretion, others are not, and that these decisions should be left with the people in question), nor require the inherently uncertain and faintly absurd estimation of an 'appropriate carbon price'.

Of course, with the current direction of politics, the catastrophic destabilisation of our climate looks far more likely than either alternative, but if we are to fight, it is important that we clearly identify the alternative course or courses worth fighting for.

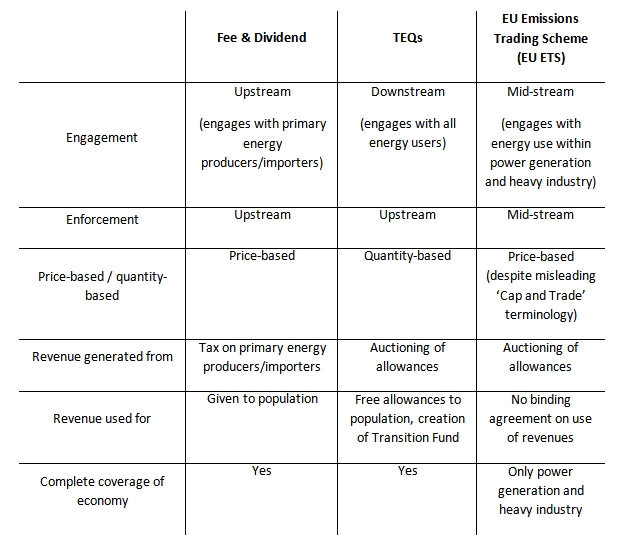

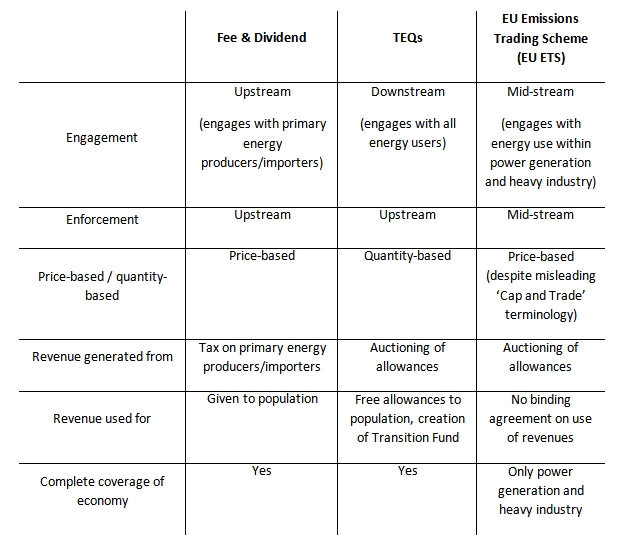

Finally, for those who prefer a more visual layout, here is a quick comparison table (also including the existing EU Emissions Trading Scheme), with thanks to Nicola Terry for the idea and initial work:

Finally, for those who prefer a more visual layout, here is a quick comparison table (also including the existing EU Emissions Trading Scheme), with thanks to Nicola Terry for the idea and initial work:

I look forward to hearing what you think, in the comments below.

---

Long-time readers may note some similarities with this 2008 post on TEQs and Cap and Dividend (an older variant - a quantity-based, upstream system), or my summer piece on the dangers of carbon pricing.

I do believe that carbon pricing is an inherently flawed approach, and that the World Bank/IMF/Big Oil's reasons for pushing it are not what they pretend - see this brilliantly straightforward explanation on that - but nonetheless, Fee & Dividend is certainly worthy of respect and discussion as the gold standard representative of that path.

I look forward to hearing what you think, in the comments below.

---

Long-time readers may note some similarities with this 2008 post on TEQs and Cap and Dividend (an older variant - a quantity-based, upstream system), or my summer piece on the dangers of carbon pricing.

I do believe that carbon pricing is an inherently flawed approach, and that the World Bank/IMF/Big Oil's reasons for pushing it are not what they pretend - see this brilliantly straightforward explanation on that - but nonetheless, Fee & Dividend is certainly worthy of respect and discussion as the gold standard representative of that path.

by Shaun Chamberlin | Nov 29, 2015 | All Posts, Cultural stories, David Fleming, Economics, Lean Logic, Reviews and recommendations

I am pleased and proud to be able to mark the 5th anniversary of my friend David Fleming's death with the news that his life's work is approaching publication.

I believe that a beautiful way to honour those we love after their death is to keep alive in the world that which was best in them. In David's case, there was no clearer way to do so than to see his masterwork Lean Logic: A Dictionary for the Future and How to Survive It reach the audience that deserves it.

As Rob Hopkins and Jonathon Porritt explain in their forewords (yet to be released), it is a book that has been hugely influential even before its publication!

The copy-edited manuscript is now with the publishers ahead of its summer release, but I thought I would mark today by sharing the new cover design (I love it!) and my introductory preface:

~~~

Editor's Preface

David Fleming was one of my closest friends; a mentor, and an inspiration. His sudden death in late 2010 came as a complete shock. At the time we were in the midst of final preparations ahead of the publication of a jointly-authored parliamentary report on his influential TEQs scheme (see the entry in this Dictionary), so getting that launched as he would have wanted was the immediate priority. It received international headlines but, for me, in the wake of the flurry of interest came the emotion, and the realisation that this book – his great work, his legacy to the world – remained unpublished.

There is no question that part of my motivation for undertaking the work on this book has been my deep love and gratitude for David, but I am driven far more by the sense that this is a genuinely important work, with a significant audience out there who deserve to read it.

For me, and for many others, it has been a touch-stone. When engaging in activities not tied to the logic of the market economy, we are forever told that our efforts are quaint and obsolete. It can be wearing, but Lean Logic is the antidote – a reminder of the deeper culture that such work is grounded in; that older ways of relating are no mirage, but rather the very foundation that society is built on; that our efforts matter more than we know. Indeed, if not for the weight, I might be tempted to carry a copy to gift to such critics!

This is, without any shadow of a doubt, a unique book. Conversations with David rank among the most startling and refreshing experiences of my life, and this book is the truest testament imaginable to the character and ingenuity of the man. The very structure of the book reflects his genius for drawing unconventional and revealing connections where they were never suspected, and it is all too easy to spend hours exploring his web of entertaining dictionary entries. And then astonishing to discover how they build, almost without being noticed, into a comprehensive vision of a radically different future. But I shall not say too much else about Lean Logic itself here, and let you experience it for yourself.

Instead, I have been asked to write a little about the past five years, and the process from the final manuscript on David’s home computer to the book you now hold in your hands.

Some of you will have come to this book after reading the paperback Surviving the Future: Culture, Carnival and Capital in the Aftermath of the Market Economy. I produced that book from this one, so your journey has been the opposite to my own, but I have had you in mind throughout, and I trust that you will find it a natural process to discover how the material from that book fits within David Fleming’s wider vision. You will encounter content that you recognise, but it will be interwoven with other material (perhaps four-fifths of this book) that will be new to you.

The rest of you are on a path more similar to mine. Although David and I worked closely in his small Hampstead flat, until only a few weeks before his death he would not let me look at Lean Logic. He said that we were too close, and the project too dear to his heart, so that we would likely fall out if I were critical! So when I found his final manuscript for this book in the weeks after his death, it was an invitation to one last glorious conversation.

Shortly afterwards, a group of David’s closest friends and family decided to self-publish 500 copies of his manuscript, as soon as possible and just as he had left it, for those who knew him and his work. Then, in 2011, we started talking with publishers about a full publication; the feedback was that a more conventional version might be necessary, as a ‘way in’ to the full work, so with advice and support from many of David’s friends – Roger Bentley and Biff Vernon especially – I tentatively started work on what would become Surviving the Future.

As that process was coming to an end, the Dark Mountain journal put out a call for submissions to their fourth book, on the theme of “post-cautionary tales”. In shock at encountering a category of any kind that Lean Logic actually seemed to fit perfectly, I felt obliged to submit some extracts. Despite being overwhelmed with submissions, the Dark Mountain team were so enamoured of the curious dictionary entries that they asked for an additional set, for their fifth book.

And that is where Michael Weaver of Chelsea Green Publishing happened across them, and so made contact to ask whether they could help in any way with publishing or distributing David’s work. Having worked with Chelsea Green before on my own Transition book, I was enthusiastic at the possibility. Initially, we discussed the publication of Surviving the Future, but quickly came to the realisation that it was most appropriate to bring the two books out concurrently, allowing readers to explore both or either, according to their taste. That brings our story up to Autumn 2014, with much of my time since spent pulling both books together into their final published form. Writing this preface is one of my final tasks; in many ways the book in your hands has been both the starting-point and the finish-line for me.

So, you can imagine how much pleasure it gives me to invite you to step into the world of Lean Logic. David bestowed the subtitle A Dictionary for the Future and How to Survive It, but, if only for want of competition, it can surely claim to be The Dictionary for the Future and How to Survive It.

But where to start with such a book? Well, one genuine answer would be “anywhere you like” – the index contains a complete list of entries to pique your interest – but if you would like some suggestions...

For full details of Lean Logic, and the chance to pre-order a copy, see the book's dedicated webpage.

For full details of Lean Logic, and the chance to pre-order a copy, see the book's dedicated webpage.

by Shaun Chamberlin | May 29, 2015 | All Posts, Climate Change, Cultural stories, Economics, Out and about, Politics, TEQs (Tradable Energy Quotas), Transition Movement

Lately we've seen the president of the World Bank and 'business leaders from the very carbon-intensive industries' pushing for carbon pricing (taxes or 'carbon trading' schemes). This is intended to demonstrate their deep change of heart and determination to start seriously addressing climate change, but to my eyes it is a deeply cynical, pernicious attempt to channel the passion of those deeply-committed to action on climate change into mechanisms that will only maintain the suicidal status quo.

Which is why I poured all my experience of ten years' work on the topic into this peer-reviewed academic paper, which I believe demolishes the case for carbon taxes or carbon trading schemes as the way forward, and shows a clear, well-researched alternative (though it took almost as much effort as writing my book!).

The paper, co-authored with Drs. Larch Maxey and Victoria Hurth, focuses on the TEQs scheme devised by the late David Fleming, the radical economist whose work was a core inspiration for the Transition Towns movement. Since meeting David in 2006 I have been rather inspired by his design for a policy framework for a society that really wanted to decarbonise. We may not live in that society yet, but it's nonetheless a rather important tool to have in the box.

Over the years that inspiration has led me to write and speak widely on TEQs (to audiences ranging from community groups, Climate Camps and Occupations to the UK Committee on Climate Change, the London School of Economics, the UK and Scottish Parliaments and the European Commission), as well as advising the UK government on their feasibility study into the scheme.

After David Fleming's sudden death in 2010, it fell to me to keep the fruits of his genius on the table, and so I created The Fleming Policy Centre to continue advocacy in light of the extensive media interest the scheme was attracting.

This new piece in the Carbon Management journal has emerged from all of that as the definitive paper on TEQs, covering its design, history and importance, and directly contrasting its hard cap on emissions with the ‘carbon pricing’ approach that has undermined public engagement with, and support for, climate policy.

I have written before about the shortcomings of global-scale action on global-scale problems, but local-scale action has its inherent problems too. Without a supportive economic/political framework in place, it is always swimming against the tide, and this can be exhausting and disheartening. As explained in the paper, TEQs provides the key framework to join up local and global scale efforts into an effective solution, making it clear to everyone - across all sectors - how to act on our intrinsic shared desires to sustain affordable access to energy and preserve a benign climate (see section on "Integration – cross-sector engagement, motivation and collaboration", pp. 8-10).

Not to mention leading to support and investment for human-scale, community-level initiatives and enterprises and local economies, making for more integrated, happier, resilient communities and a stronger sense of common purpose across society. I really believe that TEQs could catalyse a turning point towards a happier world and, more importantly, the extensive research done to date backs that up. Also, as discussed in the paper, unlike many other beautiful ideas, it actually has a hope of being implemented!

Rather than seeing our most committed people channelled into building inherently flawed 'carbon pricing' mechanisms, let's focus our energies on something genuinely radical that creates a fairer, more equitable world, and which enjoys greater public support.

I look forward to hearing what you make of our work, in the comments below or elsewhere.

~ UPDATE - This was my first venture into scientific academic writing (and likely last, after such an arduous process!), but I strove to ensure that academic-speak was kept to a minimum, and that the message is clear.

So it is gratifying to see that only a month after publication it is already in the Top 10 most-read pieces that have been published in the Carbon Management journal and, according to Altmetric, in the top 5% most discussed articles among the 4 million or so that they track! That said, it will have to have one hell of an impact to tempt me into academia ever again ;) ~

~ SECOND UPDATE - 23rd Sept 2015 - Tom Burke has published an exceptional blog post giving far more insight into the devious motivations of Big Oil in promoting carbon pricing.

And in the meantime, our paper has become the most read in the history of the Carbon Management journal, and in the top 3% most discussed on Altmetric. Despite Big Oil's best efforts, word's getting out... ~

In the meantime, I have been 'offsetting' the pain of academic writing by indulging in some deeply nourishing artivist agnosticism with Reverend Billy and his glorious Stop Shopping Choir (spot me flyering around the 1m30 mark).

A little analysis and deep thinking is important - after all “action for action's sake is the last resort of mentally and morally exhausted men” - but too much makes Jack a dull boy... I must confess, I'm rather tempted to run away and join the church. My mother would be truly horrified!

I'll have to content myself with heading to the Reclaim The Power direct action camp this weekend :) See you there?

This new piece in the Carbon Management journal has emerged from all of that as the definitive paper on TEQs, covering its design, history and importance, and directly contrasting its hard cap on emissions with the ‘carbon pricing’ approach that has undermined public engagement with, and support for, climate policy.

I have written before about the shortcomings of global-scale action on global-scale problems, but local-scale action has its inherent problems too. Without a supportive economic/political framework in place, it is always swimming against the tide, and this can be exhausting and disheartening. As explained in the paper, TEQs provides the key framework to join up local and global scale efforts into an effective solution, making it clear to everyone - across all sectors - how to act on our intrinsic shared desires to sustain affordable access to energy and preserve a benign climate (see section on "Integration – cross-sector engagement, motivation and collaboration", pp. 8-10).

Not to mention leading to support and investment for human-scale, community-level initiatives and enterprises and local economies, making for more integrated, happier, resilient communities and a stronger sense of common purpose across society. I really believe that TEQs could catalyse a turning point towards a happier world and, more importantly, the extensive research done to date backs that up. Also, as discussed in the paper, unlike many other beautiful ideas, it actually has a hope of being implemented!

Rather than seeing our most committed people channelled into building inherently flawed 'carbon pricing' mechanisms, let's focus our energies on something genuinely radical that creates a fairer, more equitable world, and which enjoys greater public support.

I look forward to hearing what you make of our work, in the comments below or elsewhere.

~ UPDATE - This was my first venture into scientific academic writing (and likely last, after such an arduous process!), but I strove to ensure that academic-speak was kept to a minimum, and that the message is clear.

So it is gratifying to see that only a month after publication it is already in the Top 10 most-read pieces that have been published in the Carbon Management journal and, according to Altmetric, in the top 5% most discussed articles among the 4 million or so that they track! That said, it will have to have one hell of an impact to tempt me into academia ever again ;) ~

~ SECOND UPDATE - 23rd Sept 2015 - Tom Burke has published an exceptional blog post giving far more insight into the devious motivations of Big Oil in promoting carbon pricing.

And in the meantime, our paper has become the most read in the history of the Carbon Management journal, and in the top 3% most discussed on Altmetric. Despite Big Oil's best efforts, word's getting out... ~

In the meantime, I have been 'offsetting' the pain of academic writing by indulging in some deeply nourishing artivist agnosticism with Reverend Billy and his glorious Stop Shopping Choir (spot me flyering around the 1m30 mark).

A little analysis and deep thinking is important - after all “action for action's sake is the last resort of mentally and morally exhausted men” - but too much makes Jack a dull boy... I must confess, I'm rather tempted to run away and join the church. My mother would be truly horrified!

I'll have to content myself with heading to the Reclaim The Power direct action camp this weekend :) See you there?

by Shaun Chamberlin | May 19, 2014 | All Posts, Cultural stories, Economics, Philosophy, Transition Movement

This post was originally written by me as a guest post for Rob Hopkins' Transition Culture blog, but I have kindly given myself permission to reproduce it here ;)

by Shaun Chamberlin | Nov 20, 2012 | All Posts, Cultural stories, Economics, Favourite posts, Politics, The right to land

The right to access land matters, in a fundamental way. It is a place to live, a source for food, for water, for fuel, and for sustenance of almost every kind. And land management also has profound impacts on our ecosystems and environment, and thus on our well-being and our collective future. So it matters deeply that while UK supermarkets and housing estates find permission to build easy to come by, those who wish to use land to explore truly sustainable living are blocked and frustrated at every turn.

It is this sorry state of affairs that has given birth to the "Reclaim the Fields" movement and activist groups like Grow Heathrow and the Diggers 2012. Inspired by the example of Gerrard Winstanley's 17th Century Diggers, these peaceful, practical radicals have moved onto disused UK land in order to cultivate it, build dwellings and live in common "by the sweat of our brow".

In other words, they have asserted their right to simply exist on nature's bounty, seeking neither permission from anyone nor dominion over anyone; a right that they believe people should still share with the other animals. A right, indeed, that was enshrined in UK law in the 1217 Charter of the Forest. More recently, however, the strange young notion of owning exclusive rights to land has pushed back hard (as this excellent article documents). Thus, as they fully expected - and as happened to their forebears - the Diggers 2012's crops have been torn up and they themselves have been hassled, moved on and in some cases arrested.

It might seem, then, that the efforts of these determined folk are being successfully repelled by 'the system', were it not for two crucial considerations - that they have history on their side, and that there is an enormous army surging at their backs.

As we look around the world, we see them, from the likes of the 1.5m strong Landless Workers' Movement in Brazil and the vast international peasant's movement La Via Campesina, to the tens of thousands of Greek families deserting the cities to return to any land they can access and the immense - and successful - land rights march across India earlier this year.

Meanwhile, closer to home, I see increasing numbers of my friends disillusioned and marginalised from the mainstream economy - ripped off by the banks, burdened with huge debts and struggling to find decent employment. As the inherently unsustainable financial economy continues to unravel, the people of England are not yet reaping the desperate consequences to the extent that those of Greece or India are, but it is growing even here, and it will come heavily home to this dark heart of the financial empire soon enough. For many, 'austerity' is already biting hard.

Naturally, in such circumstances, we seek alternatives. Yet while some might wish to follow the example of those Greek families and earn a simple, honest life "by the sweat of our brow", rather than working frantically to earn 'a living' while paying off the debts incurred by a corrupt financial system, they are simply not being permitted to do so.

New laws are being passed absurdly criminalising the likes of squatting and trespass (even against the wishes of the police forces), meaning that the police are being forced to step in on behalf of landowners. Meanwhile, planning policy reform makes it ever easier for corporations - and harder for families - to control land, leaving the courts obliged to prosecute those who wish to work to heal disused, neglected land instead of relying on state handouts to survive the vagaries of the employment market. The glaring injustice that has mobilised mass movements in the likes of Brazil and India is becoming ever more apparent here.

Thus I see the tide of history at the backs of the Diggers 2012, with their direct action the vanguard of an inevitable UK movement to reclaim the land under our feet from the 1% - or 0.06% - who would call it theirs.

Meanwhile, closer to home, I see increasing numbers of my friends disillusioned and marginalised from the mainstream economy - ripped off by the banks, burdened with huge debts and struggling to find decent employment. As the inherently unsustainable financial economy continues to unravel, the people of England are not yet reaping the desperate consequences to the extent that those of Greece or India are, but it is growing even here, and it will come heavily home to this dark heart of the financial empire soon enough. For many, 'austerity' is already biting hard.

Naturally, in such circumstances, we seek alternatives. Yet while some might wish to follow the example of those Greek families and earn a simple, honest life "by the sweat of our brow", rather than working frantically to earn 'a living' while paying off the debts incurred by a corrupt financial system, they are simply not being permitted to do so.

New laws are being passed absurdly criminalising the likes of squatting and trespass (even against the wishes of the police forces), meaning that the police are being forced to step in on behalf of landowners. Meanwhile, planning policy reform makes it ever easier for corporations - and harder for families - to control land, leaving the courts obliged to prosecute those who wish to work to heal disused, neglected land instead of relying on state handouts to survive the vagaries of the employment market. The glaring injustice that has mobilised mass movements in the likes of Brazil and India is becoming ever more apparent here.

Thus I see the tide of history at the backs of the Diggers 2012, with their direct action the vanguard of an inevitable UK movement to reclaim the land under our feet from the 1% - or 0.06% - who would call it theirs.

Yet, as with all influential movements for change in society, the activists cannot achieve much alone. Their direct action and willingness to put their bodies on the line powerfully expresses and demonstrates the ever-swelling public pressure, but if that pressure is to lead to a better society, rather than simply widespread frustration and anger, we also need positive lifestyle examples for law-abiding citizens to follow, complemented by the slow work of developing alternative legal and organisational forms that allow land to meet the pressing needs of the people.

This is why this year I agreed to become a director of an organisation called the Ecological Land Co-operative, which exists to overcome the two great barriers to land for those wishing to establish ecological businesses and smallholdings - soaring land prices and simple legal permission.

We are now on the brink of making our first area of land available, and my article in the latest edition of Permaculture Magazine (out now and highly recommended) explains how that has been done, as well as outlining the seven year journey to reach this point - with assistance from some of the leading experts on land reform - and our plans for the future. The photo at the top of this blog post shows that very piece of land; twenty-two acres in South-West England.

Crowdfunding and community financing have also allowed us to work on a pair of research reports. The first - Small Is Successful - examined existing land-based businesses of 10 acres or less and evidenced the economically viable and highly sustainable nature of the livelihoods they provide, without any need for the subsidies on which large farms so often rely. The Research Council UK showcased this as one of a hundred pieces of UK research ‘that will have a profound effect on our future’, and we have also presented our message at the House of Commons, to the All Party Parliamentary Group for Agroecology.

Yet, as with all influential movements for change in society, the activists cannot achieve much alone. Their direct action and willingness to put their bodies on the line powerfully expresses and demonstrates the ever-swelling public pressure, but if that pressure is to lead to a better society, rather than simply widespread frustration and anger, we also need positive lifestyle examples for law-abiding citizens to follow, complemented by the slow work of developing alternative legal and organisational forms that allow land to meet the pressing needs of the people.

This is why this year I agreed to become a director of an organisation called the Ecological Land Co-operative, which exists to overcome the two great barriers to land for those wishing to establish ecological businesses and smallholdings - soaring land prices and simple legal permission.

We are now on the brink of making our first area of land available, and my article in the latest edition of Permaculture Magazine (out now and highly recommended) explains how that has been done, as well as outlining the seven year journey to reach this point - with assistance from some of the leading experts on land reform - and our plans for the future. The photo at the top of this blog post shows that very piece of land; twenty-two acres in South-West England.

Crowdfunding and community financing have also allowed us to work on a pair of research reports. The first - Small Is Successful - examined existing land-based businesses of 10 acres or less and evidenced the economically viable and highly sustainable nature of the livelihoods they provide, without any need for the subsidies on which large farms so often rely. The Research Council UK showcased this as one of a hundred pieces of UK research ‘that will have a profound effect on our future’, and we have also presented our message at the House of Commons, to the All Party Parliamentary Group for Agroecology.

Our second research project has just begun; we are collaborating with others to produce a resource establishing both the current state of ecological farming in the UK - providing a single point of information on who is doing what and where, what acreages, to what markets, etc - and the current state of research into such agriculture.

I see this work as supporting and strengthening the wider movement to reclaim land from the ecologically destructive, market-driven mainstream of conventional land use. Or, if that sounds a little grand, perhaps I can borrow from one who speaks more plainly? In the words of a U.S. farmer quoted in Colin Tudge's So Shall We Reap:

"I just want to farm well. I don't want to compete with anybody."

In this world of frantic capitalism, there is a radical thought if ever I heard one.

It is a thought that inspires me. I feel more and more that the people the world needs most right now are not campaigners or activists, but such people who simply wish to live in relationship with a piece of land in a healing, productive and ecologically nurturing way. There is no shortage of them, and we should be making it as easy as possible for them to access land, without forcing them to launch political campaigns or planning permission battles in order to do so.

Perhaps that vast and diverse movement - from La Via Campesina and the Diggers 2012 to the Eco Land Co-op - in truth has but one simple aim. To safeguard the quiet dignity of that farmer, and the billions like him.

Our second research project has just begun; we are collaborating with others to produce a resource establishing both the current state of ecological farming in the UK - providing a single point of information on who is doing what and where, what acreages, to what markets, etc - and the current state of research into such agriculture.

I see this work as supporting and strengthening the wider movement to reclaim land from the ecologically destructive, market-driven mainstream of conventional land use. Or, if that sounds a little grand, perhaps I can borrow from one who speaks more plainly? In the words of a U.S. farmer quoted in Colin Tudge's So Shall We Reap:

"I just want to farm well. I don't want to compete with anybody."

In this world of frantic capitalism, there is a radical thought if ever I heard one.

It is a thought that inspires me. I feel more and more that the people the world needs most right now are not campaigners or activists, but such people who simply wish to live in relationship with a piece of land in a healing, productive and ecologically nurturing way. There is no shortage of them, and we should be making it as easy as possible for them to access land, without forcing them to launch political campaigns or planning permission battles in order to do so.

Perhaps that vast and diverse movement - from La Via Campesina and the Diggers 2012 to the Eco Land Co-op - in truth has but one simple aim. To safeguard the quiet dignity of that farmer, and the billions like him.

From the manifesto of The Land magazine:

"...Rarely will you hear someone with access to a microphone mouth the word "land".

That is because economists define wealth and justice in terms of access to the market. Politicians echo the economists because the more dependent that people become upon the market, the more securely they can be roped into the fiscal and political hierarchy. Access to land is not simply a threat to landowning élites — it is a threat to the religion of unlimited economic growth and the power structure that depends upon it.

The market (however attractive it may appear) is built on promises: the only source of wealth is the earth. Anyone who has land has access to energy, water, nourishment, shelter, healing, wisdom, ancestors and a grave.

...Yet the earth is more than a tool cupboard, for although the earth gives, it dictates its terms; and its terms alter from place to place. So it is that agriculture begets human culture; and cultural diversity, like biological diversity, flowers in obedience to the conditions that the earth imposes. The first and inevitable effect of the global market is to uproot and destroy land-based human cultures. The final and inevitable achievement of a rootless global market will be to destroy itself.

In a shrunken world, taxed to keep the wheels of industry accelerating, land and its resources are increasingly contested. Seven billion people compete to acquire land for a variety of conflicting uses: land for food, for water, for energy, for timber, for carbon sinks, for housing, for wildlife, for recreation, for investment. The politics of land — who owns it, who controls it and who has access to it — is more important than ever, though you might not think so from a superficial reading of government policy and the media.

...Rome fell; the Soviet Empire collapsed; the stars and stripes are fading in the west. Nothing is forever in history, except geography. Capitalism is a confidence trick, a dazzling edifice built on paper promises. It may stand longer than some of us anticipate, but when it crumbles, the land will remain."

--

Full details of Shaun's extensive tour in support of the books available here.

Latest info on the books, reviews etc, including the audiobook/film versions, available here.

--

Full details of Shaun's extensive tour in support of the books available here.

Latest info on the books, reviews etc, including the audiobook/film versions, available here.

Yet, as with all influential movements for change in society, the activists cannot achieve much alone. Their direct action and willingness to put their bodies on the line powerfully expresses and demonstrates the ever-swelling public pressure, but if that pressure is to lead to a better society, rather than simply widespread frustration and anger, we also need

Yet, as with all influential movements for change in society, the activists cannot achieve much alone. Their direct action and willingness to put their bodies on the line powerfully expresses and demonstrates the ever-swelling public pressure, but if that pressure is to lead to a better society, rather than simply widespread frustration and anger, we also need

Recent Comments