by Shaun Chamberlin | May 17, 2012 | All Posts, Cultural stories, David Fleming, Economics, Favourite posts, Politics, The Transition Timeline, Transition Movement

Last month I was one of forty or so attendees of the Transition ‘Peak Money’ day. It was a fascinating collection of people, from theorists to activists, and a potent opportunity to reflect on the challenges facing us all as the glaring errors at the heart...

by Shaun Chamberlin | Jul 23, 2011 | All Posts, Cultural stories, Reviews and recommendations, The Transition Timeline, Transition Movement

As regular readers will know, I am an admirer of the Dark Mountain Project – fellow adventurers in uncovering and reshaping the cultural stories that define us and guide our behaviour. Their manifesto is well worth a read. So I have accepted this contribution...

by Shaun Chamberlin | Feb 11, 2011 | All Posts, Cultural stories, Reviews and recommendations, The Transition Timeline, Transition Movement

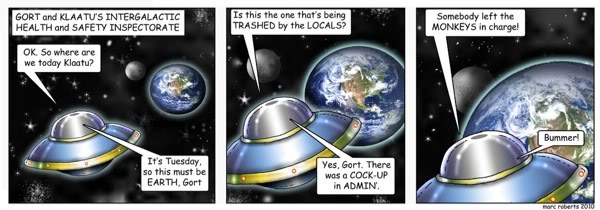

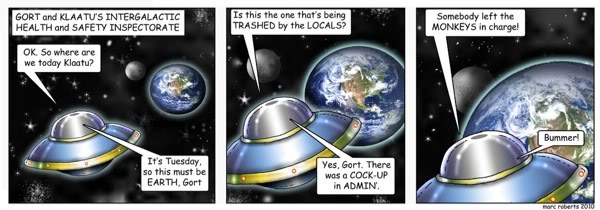

The brilliant cartoonist Marc Roberts (whose work will be familiar to regular Dark Optimism readers) got in touch with the Transition Network last year offering to produce a strip exploring the Transition concept. The time has come for the results to be unleashed on...

by Shaun Chamberlin | Jun 9, 2010 | All Posts, Climate Change, Cultural stories, Favourite posts, Peak Oil, TEQs (Tradable Energy Quotas), The Transition Timeline, Transition Movement

https://www.darkoptimism.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/10-03-26-Radio-EcoShock_Chamberlin_LoFi.mp3 Christopher Fraser of London Transition has kindly transcribed the above popular interview with Canada’s Radio Ecoshock that I posted a couple of months back....

by Shaun Chamberlin | Mar 28, 2010 | All Posts, Climate Change, Cultural stories, Peak Oil, TEQs (Tradable Energy Quotas), The Transition Timeline, Transition Movement

https://www.darkoptimism.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/10-03-26-Radio-EcoShock_Chamberlin_LoFi.mp3 Above is a 24 minute interview I did last week with Canada’s excellent Radio Ecoshock. The full 60 minute show can be heard here. Dark Optimism readers may also...

by Shaun Chamberlin | Feb 23, 2010 | All Posts, Cultural stories, Favourite posts, Peak Oil, Philosophy, The Transition Timeline

Below the cut is the text of my latest article for the highly-recommended Resurgence magazine. They asked me to tell the story of my own personal journey thus far, and how I ended up doing what I do. Thanks to Resurgence for permission to reproduce it here (and on my...

Recent Comments