by Shaun Chamberlin | Dec 13, 2008 | All Posts, Cultural stories, Philosophy, The Transition Timeline, Transition Movement

“A person will worship something, have no doubt about that. We may think our tribute is paid in secret in the dark recesses of our hearts, but it will out. That which dominates our imaginations and our thoughts will determine our lives, and our character....

by Shaun Chamberlin | Jul 27, 2008 | All Posts, Climate Change, Cultural stories, Favourite posts, Philosophy, Politics

Since my earlier review of Burn Up I have discovered a comment on the film posted yesterday by Jeremy Leggett, one of the few with any media profile to openly discuss the interplay of peak oil and climate change. In his piece Leggett asks: “Why do the...

by Shaun Chamberlin | Jul 11, 2008 | All Posts, Climate Change, Cultural stories, Favourite posts, Philosophy

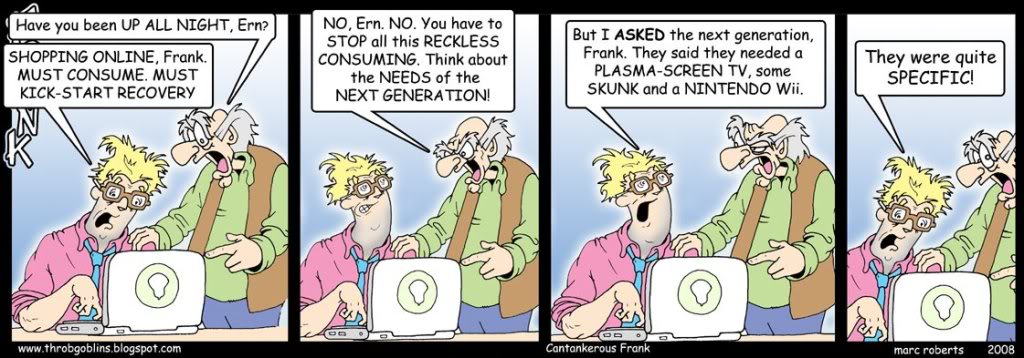

Those of you who know me personally will be aware that the indescribable exhilaration of physical movement to music (more commonly termed ‘dancing’) is my greatest release and joy. Over the past couple of weeks I have been much enjoying the latest...

by Shaun Chamberlin | Jun 29, 2008 | All Posts, Climate Change, Cultural stories, Favourite posts, Peak Oil, Philosophy, Reviews and recommendations, TEQs (Tradable Energy Quotas), Transition Movement

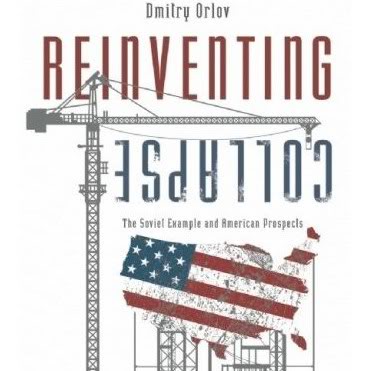

As George Carlin once said, “they call it the American dream because you have to be asleep to believe in it”. At the risk of this blog becoming ‘review corner’, that seems the perfect introduction to the book I just finished reading — Dmitry...

Recent Comments