by Shaun Chamberlin | Sep 8, 2016 | All Posts, David Fleming, Lean Logic, Out and about, Reviews and recommendations, Surviving the Future

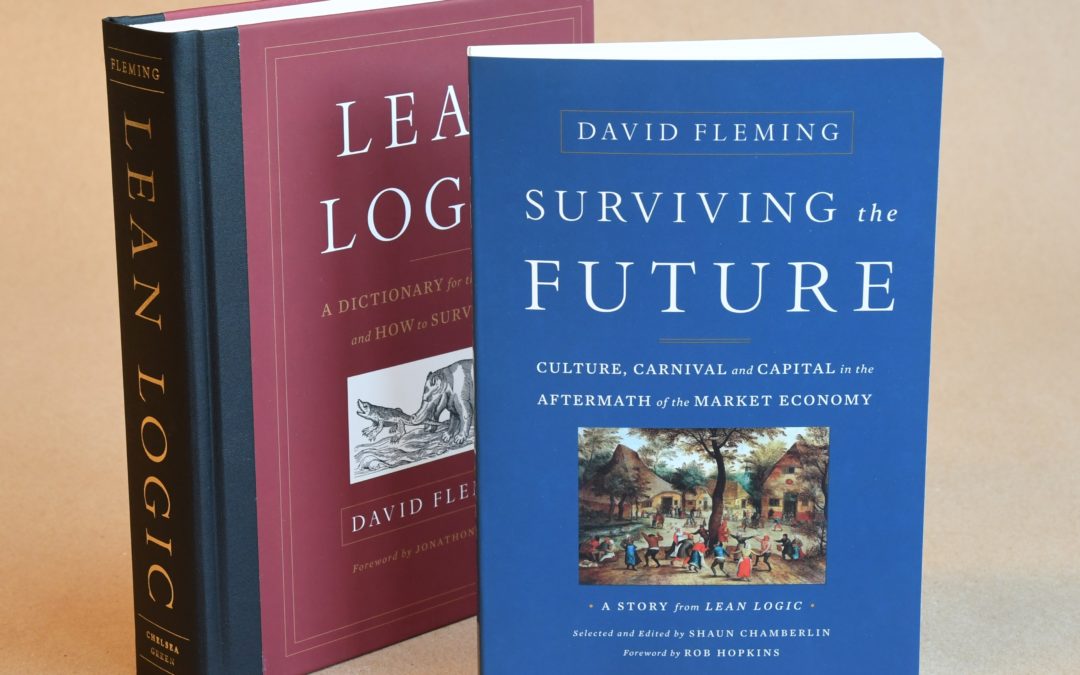

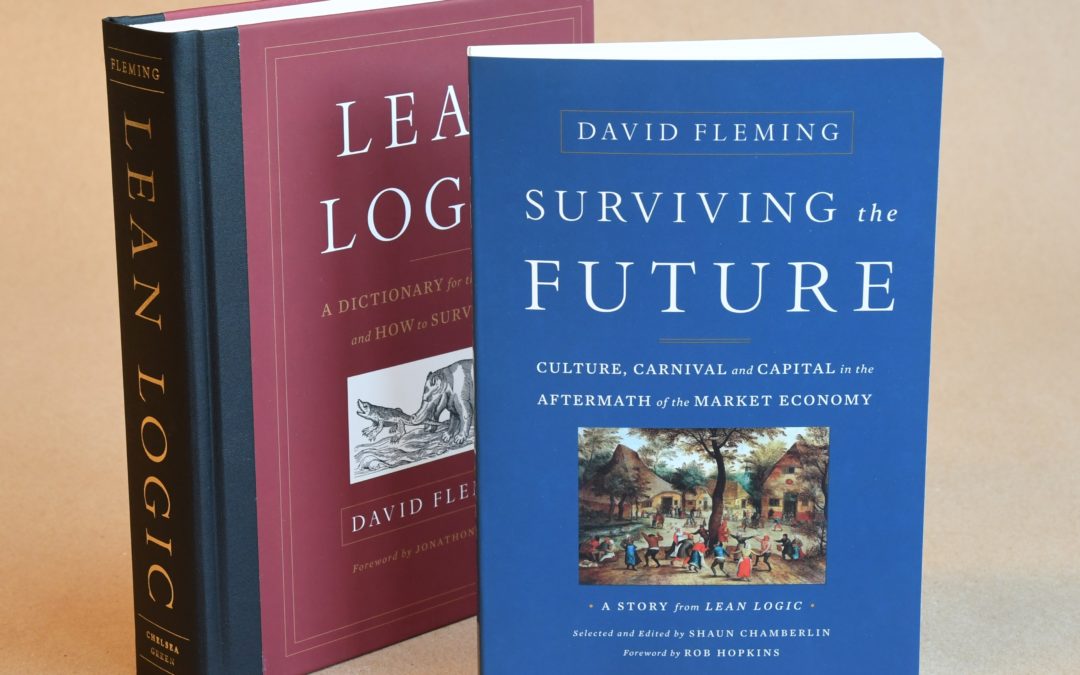

So, after years of work from me, and decades from David, the day is finally here – the official publication date for his astonishing lifework!! In truth, demand has already been such that the distributors have been struggling to keep up, but they’re...

by Shaun Chamberlin | Aug 21, 2016 | All Posts, David Fleming, Economics, Lean Logic, Reviews and recommendations, Surviving the Future, TEQs (Tradable Energy Quotas)

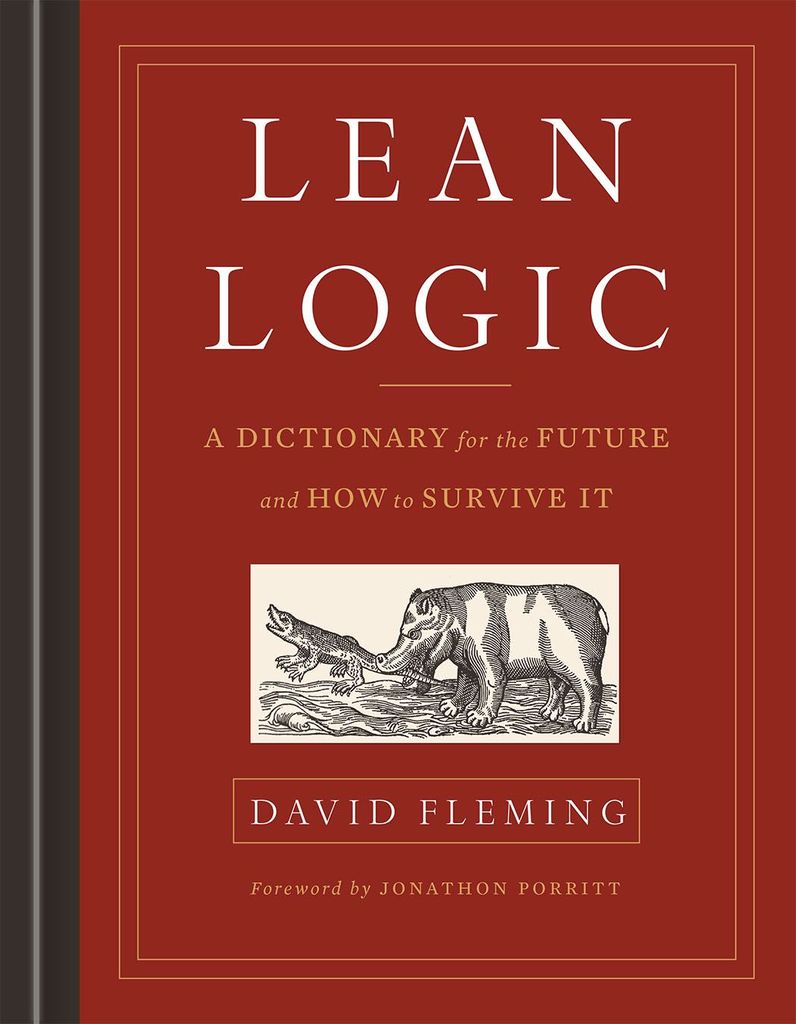

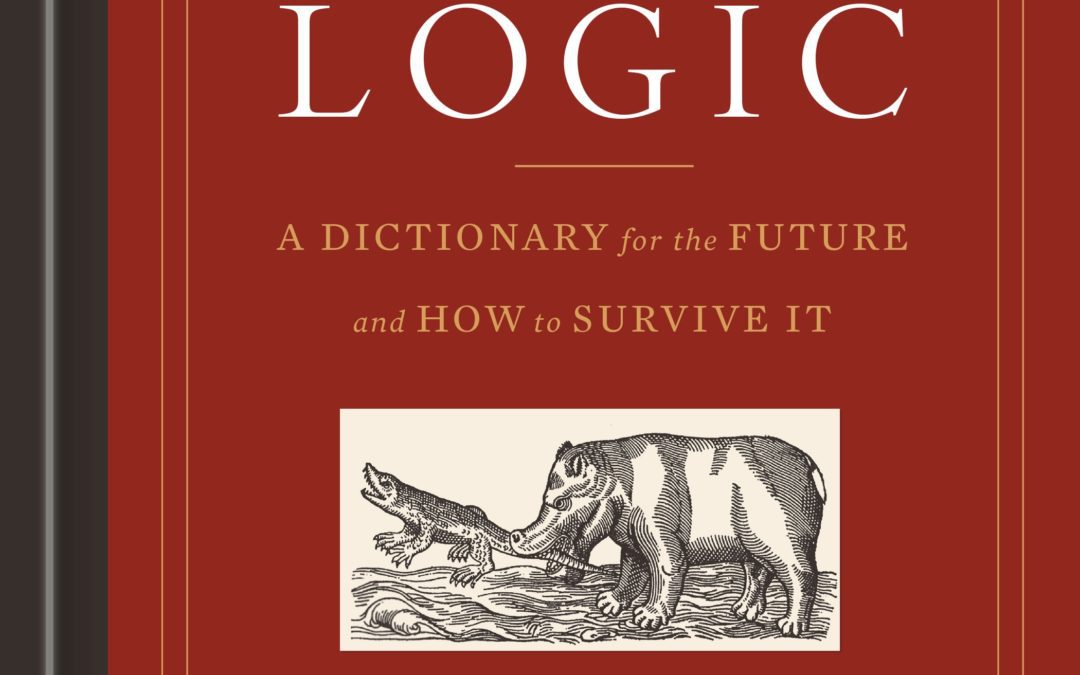

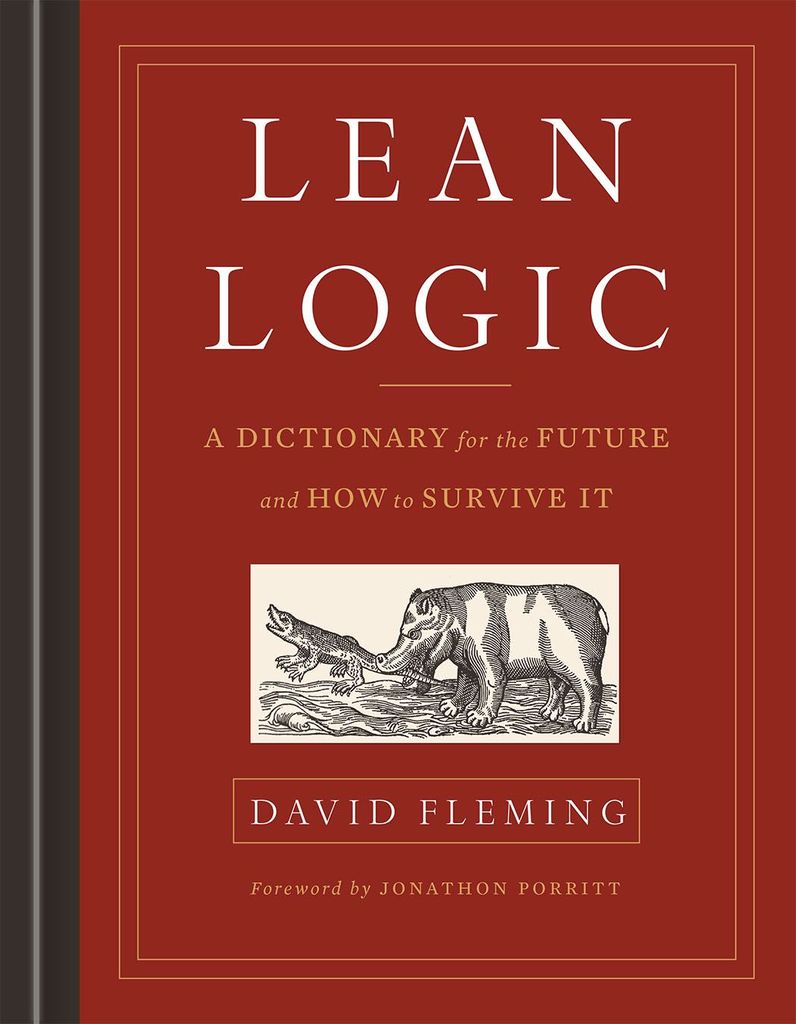

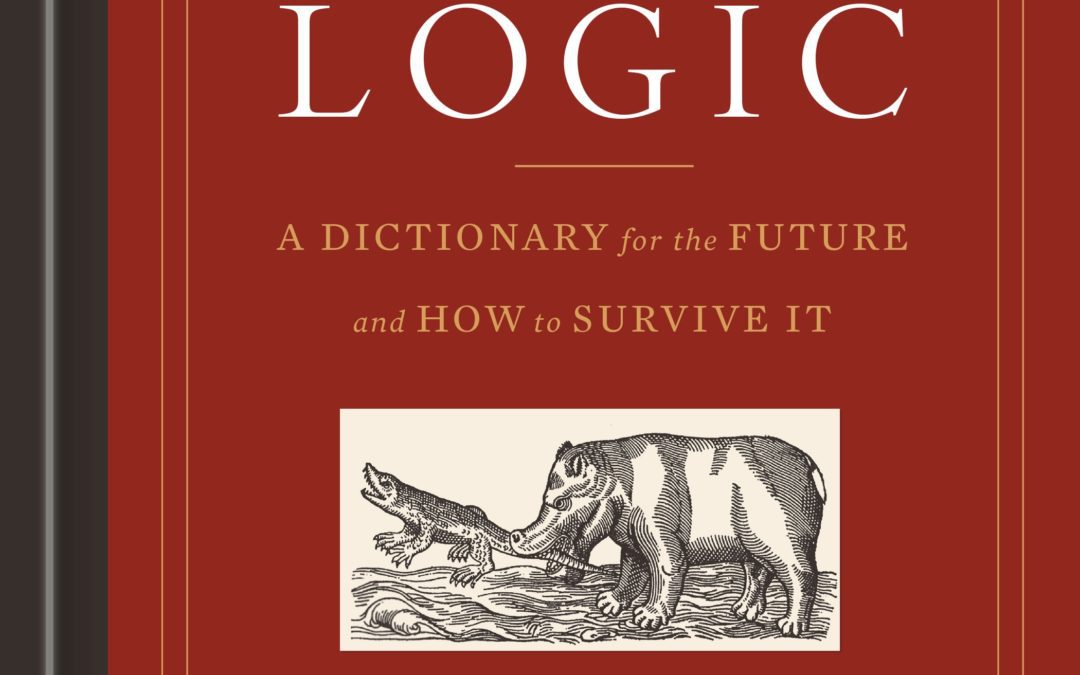

Last week the wonderful Brianne Goodspeed of Chelsea Green Publishing interviewed me on my late mentor David Fleming and the astonishing gift he left to the world. His sudden death in 2010 left behind his great unpublished work—Lean Logic: A Dictionary for the Future...

by Shaun Chamberlin | Jun 22, 2016 | All Posts, Cultural stories, David Fleming, Lean Logic, Politics

On the eve of the #Brexit referendum, I have found myself struck by the juxtaposition of two exceptional pieces of writing which run somewhat deeper than the 'lowest common denominator' debate running in the mainstream media.

It wasn't immediately clear to me which way I would vote, but reading these nuanced pieces - which draw out sensible reasons for considering both sides of the argument - helped me to make a decision.

The first is this piece by Giles Fraser in The Guardian. I believe Fraser has declared that he will vote 'Out', yet unlike many 'Brexiteers' his piece makes a crucial argument in favour of free movement for people:

---

National borders exist to pen poor people into reservations of poverty

Why, in this era of advanced globalisation, do we believe in free trade and the free movement of goods, but not in the free movement of labour?

~Rev. Giles Fraser~

He is not one of my regulars. From Cameroon, he says. And hungry, poor bloke. I can tell he’s had to swallow a lot of pride to beg for food at my door. I apologise to him, say that because we’ve just made a delivery to the food bank, the church is out of supplies. And personally, I haven’t done a shop in days. I rummage around in my cupboards and come up with an avocado and some spaghetti hoops, which really isn’t good enough. Is there any work out there, I ask him. It’s hard to find without the right papers, he says. Bloody Home Office, I say. He smiles.

We are so hypocritical about borders. We cheer when the Berlin Wall comes down. We condemn the Israelis for their separation barrier and Donald Trump for his ludicrous Mexican fence. But are we really so different? We also police our borders with guns and razor wire as if we had some God-given right to this particular stretch of land. Through the random lottery of life, I have a UK passport. I didn’t work for it or do anything whatsoever to deserve it. In economic terms, I just happened to be born lucky. My new friend from Cameroon, not so much.

Within our own borders we complain at any suggestion of a postcode lottery. When the north of England has a different standard of healthcare to the south, we consider it a scandal. But when the global north has a radically different standard of healthcare to the global south, we think that’s just the way it is. In fact, it’s far worse than that – we somehow think it our duty to fence off our advantage, to protect it against those who would share in our good fortune. And these people we disparage as illegal immigrants, as if they are thieves or terrorists – though they are just doing globally what Norman Tebbit famously advised millions of unemployed in the 1980s to do: to get on their bike and look for work.

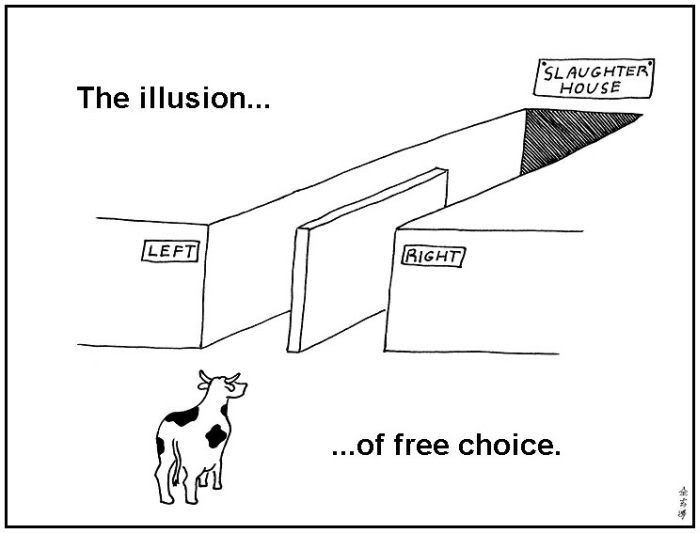

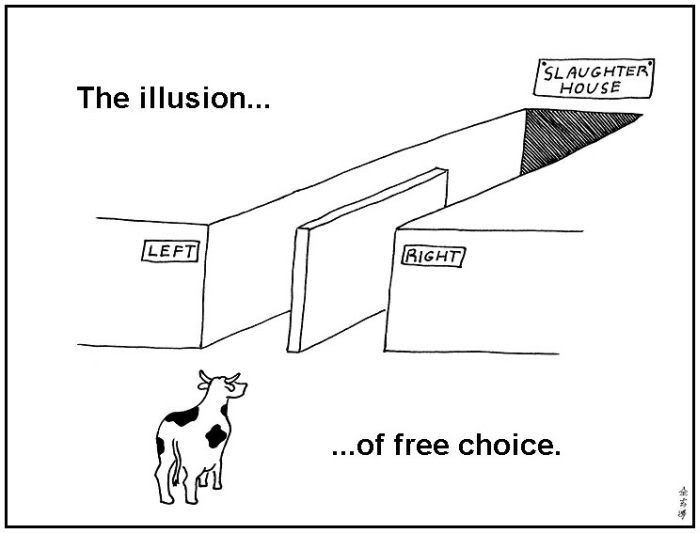

In this era of advanced globalisation, we believe in free trade, in the free movement of goods, but not in the free movement of labour. We think it outrageous that the Chinese block Google, believing it to be everyone’s right to roam free digitally. We celebrate organisations such as Médecins Sans Frontières for their compassionate universalism. But for all this talk of freedom from restriction, we still pen poor people into reservations of poverty. It’s like our own little version of The Hunger Games. And it is so normal to us, we don’t even recognise it as a moral issue.

The free movement of people is what political scientist JW Moses called “the last frontier of globalisation”, implying that it too will fall. Because, in the grand scheme of things, of course, no force on earth can insulate us against billions of people without enough to eat. Many will tragically drown in our Mediterranean moat, others will be stopped for a while at our fences, but nothing will stop more people from trying to come. And eventually they will succeed. Artificial national boundaries, just lines on a map, are no match against the massed forces of human need. This week I met in London a guy I last saw in Calais trying to get into the back of a truck. It took him months of trying to get past our borders. But in the end he made it. And good for him.

Before the Aliens Act of 1905, the UK had no border controls to speak of. They were first erected to stop Jews coming from eastern Europe. “England for the English,” was the slogan. The Manchester Evening Chronicle explained what this meant: “That the dirty, destitute, diseased, verminous and criminal foreigner who dumps himself on our soil and rates simultaneously, shall be forbidden to land.”

Border controls have always been racist in character. And it’s much the same today. They are about locking in our wealth and keeping mosques out of the Cotswolds. At present, globalisation is a luxury of the rich, for those of us who can swan about the globe with the flick of a boarding pass. The so-called “migrant crisis” is globalisation for the poor. They are blowing their trumpets around our walls. And our walls will fall.

---

The second piece is this extract from the late David Fleming's Dictionary for the Future, which I have been editing in preparation for its release next month.

It is the dictionary's entry on "Closed Access", building on Elinor Ostrom's Nobel Prize winning work on the concept of the commons:

(the *s are pointers to related entries in the dictionary)

---

He is not one of my regulars. From Cameroon, he says. And hungry, poor bloke. I can tell he’s had to swallow a lot of pride to beg for food at my door. I apologise to him, say that because we’ve just made a delivery to the food bank, the church is out of supplies. And personally, I haven’t done a shop in days. I rummage around in my cupboards and come up with an avocado and some spaghetti hoops, which really isn’t good enough. Is there any work out there, I ask him. It’s hard to find without the right papers, he says. Bloody Home Office, I say. He smiles.

We are so hypocritical about borders. We cheer when the Berlin Wall comes down. We condemn the Israelis for their separation barrier and Donald Trump for his ludicrous Mexican fence. But are we really so different? We also police our borders with guns and razor wire as if we had some God-given right to this particular stretch of land. Through the random lottery of life, I have a UK passport. I didn’t work for it or do anything whatsoever to deserve it. In economic terms, I just happened to be born lucky. My new friend from Cameroon, not so much.

Within our own borders we complain at any suggestion of a postcode lottery. When the north of England has a different standard of healthcare to the south, we consider it a scandal. But when the global north has a radically different standard of healthcare to the global south, we think that’s just the way it is. In fact, it’s far worse than that – we somehow think it our duty to fence off our advantage, to protect it against those who would share in our good fortune. And these people we disparage as illegal immigrants, as if they are thieves or terrorists – though they are just doing globally what Norman Tebbit famously advised millions of unemployed in the 1980s to do: to get on their bike and look for work.

In this era of advanced globalisation, we believe in free trade, in the free movement of goods, but not in the free movement of labour. We think it outrageous that the Chinese block Google, believing it to be everyone’s right to roam free digitally. We celebrate organisations such as Médecins Sans Frontières for their compassionate universalism. But for all this talk of freedom from restriction, we still pen poor people into reservations of poverty. It’s like our own little version of The Hunger Games. And it is so normal to us, we don’t even recognise it as a moral issue.

The free movement of people is what political scientist JW Moses called “the last frontier of globalisation”, implying that it too will fall. Because, in the grand scheme of things, of course, no force on earth can insulate us against billions of people without enough to eat. Many will tragically drown in our Mediterranean moat, others will be stopped for a while at our fences, but nothing will stop more people from trying to come. And eventually they will succeed. Artificial national boundaries, just lines on a map, are no match against the massed forces of human need. This week I met in London a guy I last saw in Calais trying to get into the back of a truck. It took him months of trying to get past our borders. But in the end he made it. And good for him.

Before the Aliens Act of 1905, the UK had no border controls to speak of. They were first erected to stop Jews coming from eastern Europe. “England for the English,” was the slogan. The Manchester Evening Chronicle explained what this meant: “That the dirty, destitute, diseased, verminous and criminal foreigner who dumps himself on our soil and rates simultaneously, shall be forbidden to land.”

Border controls have always been racist in character. And it’s much the same today. They are about locking in our wealth and keeping mosques out of the Cotswolds. At present, globalisation is a luxury of the rich, for those of us who can swan about the globe with the flick of a boarding pass. The so-called “migrant crisis” is globalisation for the poor. They are blowing their trumpets around our walls. And our walls will fall.

---

The second piece is this extract from the late David Fleming's Dictionary for the Future, which I have been editing in preparation for its release next month.

It is the dictionary's entry on "Closed Access", building on Elinor Ostrom's Nobel Prize winning work on the concept of the commons:

(the *s are pointers to related entries in the dictionary)

---

Closed Access. A *necessary condition for the management of a *commons. With limited numbers of people within its boundaries, the demands made on it, too, are limited, making them realistic and *sustainable.

The members of a managed commons must undertake to comply with the rules necessary for its maintenance; it follows that they must exclude others who do not comply with those rules, or whose demands would exceed the limits of what it can supply.

The principle underlying this is known as “subtractivity”, or “rivalness”—the idea that what one person harvests from a resource subtracts from the ability of others to do the same. There is a simple recognition here of the objective reality of the resource: it has its limits, and no amount of technical trickery or *emotional pleading can make that fact go away. Recognising subtractivity is a case of growing up—as in realising that the powers of your parents to provide are not unlimited; moving on from the child-think of unqualified confidence that the*political economy you live in can provide.

And a second principle follows from this. If the resource is limited, then there has to be some way of excluding people who, if their access were unlimited, would destroy it. That is, there has to be a way of defending it, which may be relatively straightforward in the case of, say, farmland, but is harder in the case of a fishery, or a forest, or a river, or a culture, or an atmosphere with a limited ability to absorb *waste; it is also harder when the damage caused by exceeding the limits will only become evident in the future, by which time it may be too late to repair.

This is an especially difficult problem for a super-scale *civic society such as our own. Our *size, *growth and *technical powers insulate us for a time from having to think about the limits to the resources we depend on. There therefore seems to be no need to think about the cost of *protecting them. Maybe we can all be free riders, benefiting from assets which we have done nothing to produce or protect: we can affirm a liberal right to be a free rider. It is an attractive, inclusive philosophy. It would be immoral to disagree with it—until, that is, it comes face-to-face with the laws of physics.

For the human societies to which the laws of physics are more immediately evident, closed access is the determining and shaping property of their *culture. This does not by any means imply a Scrooge-like hoarding of an underused resource without regard for the needs of other people who could make use of it. Closed access, once established as the enabling condition for the sustainable management of the commons, can provide the foundations for an extensive and rich culture of sharing and generosity: it can be expected to allow access to others for particular purposes, such as harvesting medicinal plants, or hunting a prey across the territory; it is able up to a point to share the proceeds on a regular basis. Sometimes a softening of strict closed access extends to “sleeping territoriality”, in which, say, a Pacific island reserves the right to exclusive access of a fishing-ground, but applies it only at times of scarcity. What we might see as uncaring exclusion is seen by the participants in a closed-access commons as responsibility, as belonging to the land:

Closed Access. A *necessary condition for the management of a *commons. With limited numbers of people within its boundaries, the demands made on it, too, are limited, making them realistic and *sustainable.

The members of a managed commons must undertake to comply with the rules necessary for its maintenance; it follows that they must exclude others who do not comply with those rules, or whose demands would exceed the limits of what it can supply.

The principle underlying this is known as “subtractivity”, or “rivalness”—the idea that what one person harvests from a resource subtracts from the ability of others to do the same. There is a simple recognition here of the objective reality of the resource: it has its limits, and no amount of technical trickery or *emotional pleading can make that fact go away. Recognising subtractivity is a case of growing up—as in realising that the powers of your parents to provide are not unlimited; moving on from the child-think of unqualified confidence that the*political economy you live in can provide.

And a second principle follows from this. If the resource is limited, then there has to be some way of excluding people who, if their access were unlimited, would destroy it. That is, there has to be a way of defending it, which may be relatively straightforward in the case of, say, farmland, but is harder in the case of a fishery, or a forest, or a river, or a culture, or an atmosphere with a limited ability to absorb *waste; it is also harder when the damage caused by exceeding the limits will only become evident in the future, by which time it may be too late to repair.

This is an especially difficult problem for a super-scale *civic society such as our own. Our *size, *growth and *technical powers insulate us for a time from having to think about the limits to the resources we depend on. There therefore seems to be no need to think about the cost of *protecting them. Maybe we can all be free riders, benefiting from assets which we have done nothing to produce or protect: we can affirm a liberal right to be a free rider. It is an attractive, inclusive philosophy. It would be immoral to disagree with it—until, that is, it comes face-to-face with the laws of physics.

For the human societies to which the laws of physics are more immediately evident, closed access is the determining and shaping property of their *culture. This does not by any means imply a Scrooge-like hoarding of an underused resource without regard for the needs of other people who could make use of it. Closed access, once established as the enabling condition for the sustainable management of the commons, can provide the foundations for an extensive and rich culture of sharing and generosity: it can be expected to allow access to others for particular purposes, such as harvesting medicinal plants, or hunting a prey across the territory; it is able up to a point to share the proceeds on a regular basis. Sometimes a softening of strict closed access extends to “sleeping territoriality”, in which, say, a Pacific island reserves the right to exclusive access of a fishing-ground, but applies it only at times of scarcity. What we might see as uncaring exclusion is seen by the participants in a closed-access commons as responsibility, as belonging to the land:

"Expression of worldview through respect, patience and humility; and people being viewed as a part of nature are common in traditional communities. The Lax’skiik and Gitksan of British Columbia, in general, have a personal and spiritual identification with their territories and resources, which form the basis of their cultural and economic life."

But, in order for qualities of sharing and altruism to happen, the responsibility of a particular group, and their ability to sustain the commons and determine access to it, must be unambiguously defined:

"...the management of common property is impossible unless the land is owned by a well-defined community."

The alternative is the ‘Tragedy of the *Commons’, the destruction of a common resource as individuals make ever-greater demands on it, benefiting from what they can get individually, but not seeing as their problem the damage done by those ever-greater demands to the commons as a whole. This is a Tragedy created by the global *market economy, which has destroyed the community cohesion essential to the long-term management of commons.

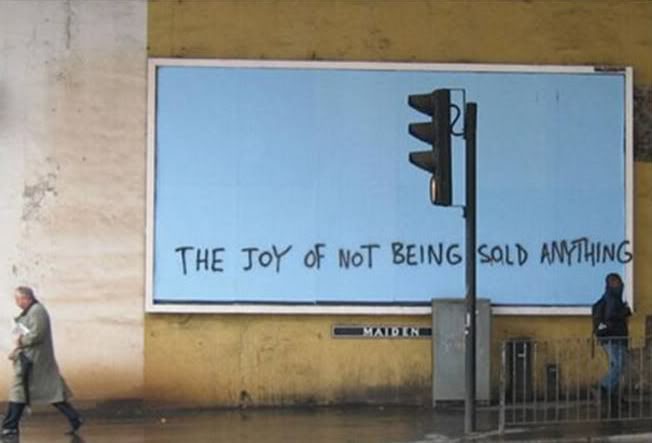

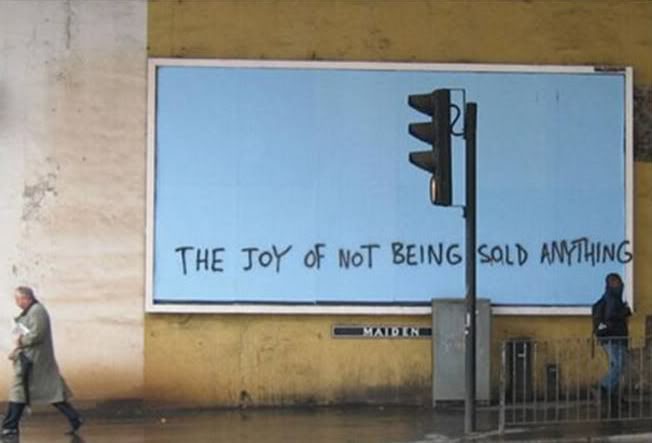

In a society used to cheap travel, and to the idea that destruction—when it comes to *boundaries and the *rhetoric about “tearing-down barriers”—is a good thing, the idea of closed access at first invites unease; there is a sense both of being locked-in, and of unfairly locking-out. But in fact it works the other way. Almost wherever you go in the market economy, you find yourself in the same place—in the globalised market with its shared banality, its fullness; at the end of every lane is a busy road and a housing estate like the one at the beginning of it.

You cannot get out of a *globalised world, because there is no out. Closed access does not mean closed-in, it means the protection of distinctiveness: when you are out, you are somewhere else, in a different in.

---

At first reading, these two pieces seemed to be in contradiction with each other, yet both made clear sense to me - especially given that 'the commons' has been core to the only sustainable societies the planet has seen. This confusing juxtaposition got my attention, because it clearly had something to teach me.

After some reflection, integrating the two perspectives seems to demand a recognition that those of us inside the walled palaces are collectively acting as free riders - taking no responsibility for the resources and ecologies that we benefit from.

We of course recognise that there must be a limit to the number of people who can be supported in the manner to which we are accustomed (by accident of birth, as Fraser says), and so many instinctively want to defend 'our land' from overwhelm. Then we draw an arbitrary line of entitlement - of 'us' - perhaps around those who were born here, and declare those who were not to be 'them'. As Fraser highlights, this is morally unjustifiable (especially since so much of our wealth is taken from other nations).

But both sides of that debate rarely follow the analysis to its logical conclusion and accept the corresponding need to take practical responsibility for caring for the place we live (whether born there or not). Since there is little acknowledgement that most native Brits are free riders, the argument never gets beyond whether we should open the doors to allow others to strive for similar lifestyles or not.

Yet if we could get past "us and them" altogether, the underlying question of limits - of "subtractivity" - would still await us. Wherever people come from, no place can support unlimited numbers of free riders (and to be honest, having worked with asylum seekers and refugees in the UK, I tend to think they are far from the main culprits in this regard).

---

Then there is the question of closed access on the global scale - taking us straight into questions of global population.

In a sense our planet itself also has a border - that between the living and the as-yet-unborn. I find it interesting to consider the immigration debates in the light of this border, and apply the same arguments here, such as:

Should more potential humans be stopped at the border and excluded from our global commons..?

Should more already-living non-humans be forced to emigrate..?

The late David Fleming has already emigrated across this border, so gets no vote on #Brexit. I believe Giles Fraser has declared that he will vote 'Out'.

As for me, like Noam Chomsky, I'm left without any strong allegiance in the Brexit debate, but I am concerned that a more independent Britain would likely be even more environmentally destructive than it currently is, and that a national 'out' vote would only be perceived as the voice of xenophobia. So I voted "in" - with slight apologies to the rest of Europe for inflicting our politics on them - but I can't escape the feeling that it's really somewhat beside the point.

What gets my juices flowing is avoiding something with far clearer consequences for all of us - #Gaiexit.

But both sides of that debate rarely follow the analysis to its logical conclusion and accept the corresponding need to take practical responsibility for caring for the place we live (whether born there or not). Since there is little acknowledgement that most native Brits are free riders, the argument never gets beyond whether we should open the doors to allow others to strive for similar lifestyles or not.

Yet if we could get past "us and them" altogether, the underlying question of limits - of "subtractivity" - would still await us. Wherever people come from, no place can support unlimited numbers of free riders (and to be honest, having worked with asylum seekers and refugees in the UK, I tend to think they are far from the main culprits in this regard).

---

Then there is the question of closed access on the global scale - taking us straight into questions of global population.

In a sense our planet itself also has a border - that between the living and the as-yet-unborn. I find it interesting to consider the immigration debates in the light of this border, and apply the same arguments here, such as:

Should more potential humans be stopped at the border and excluded from our global commons..?

Should more already-living non-humans be forced to emigrate..?

The late David Fleming has already emigrated across this border, so gets no vote on #Brexit. I believe Giles Fraser has declared that he will vote 'Out'.

As for me, like Noam Chomsky, I'm left without any strong allegiance in the Brexit debate, but I am concerned that a more independent Britain would likely be even more environmentally destructive than it currently is, and that a national 'out' vote would only be perceived as the voice of xenophobia. So I voted "in" - with slight apologies to the rest of Europe for inflicting our politics on them - but I can't escape the feeling that it's really somewhat beside the point.

What gets my juices flowing is avoiding something with far clearer consequences for all of us - #Gaiexit.

by Shaun Chamberlin | Nov 29, 2015 | All Posts, Cultural stories, David Fleming, Economics, Lean Logic, Reviews and recommendations

I am pleased and proud to be able to mark the 5th anniversary of my friend David Fleming‘s death with the news that his life’s work is approaching publication. I believe that a beautiful way to honour those we love after their death is to keep alive in the...

by Shaun Chamberlin | Jun 19, 2015 | All Posts, Cultural stories, David Fleming, Lean Logic

I am currently hunkered down working on a project close to my heart, editing my late friend and colleague Dr. David Fleming‘s incredible life’s work Lean Logic: A Dictionary for the Future and How to Survive It, for its publication by Chelsea Green later...

by Shaun Chamberlin | May 17, 2012 | All Posts, Cultural stories, David Fleming, Economics, Favourite posts, Politics, The Transition Timeline, Transition Movement

Last month I was one of forty or so attendees of the Transition ‘Peak Money’ day. It was a fascinating collection of people, from theorists to activists, and a potent opportunity to reflect on the challenges facing us all as the glaring errors at the heart...

But both sides of that debate rarely follow the analysis to its logical conclusion and accept the corresponding need to take practical responsibility for caring for the place we live (whether born there or not). Since there is little acknowledgement that most native Brits are free riders, the argument never gets beyond whether we should open the doors to allow others to strive for similar lifestyles or not.

Yet if we could get past "us and them" altogether, the underlying question of limits - of "subtractivity" - would still await us. Wherever people come from, no place can support unlimited numbers of free riders (and to be honest, having worked with asylum seekers and refugees in the UK, I tend to think they are far from the main culprits in this regard).

But both sides of that debate rarely follow the analysis to its logical conclusion and accept the corresponding need to take practical responsibility for caring for the place we live (whether born there or not). Since there is little acknowledgement that most native Brits are free riders, the argument never gets beyond whether we should open the doors to allow others to strive for similar lifestyles or not.

Yet if we could get past "us and them" altogether, the underlying question of limits - of "subtractivity" - would still await us. Wherever people come from, no place can support unlimited numbers of free riders (and to be honest, having worked with asylum seekers and refugees in the UK, I tend to think they are far from the main culprits in this regard).

Recent Comments