by Shaun Chamberlin | Aug 21, 2016 | All Posts, David Fleming, Economics, Lean Logic, Reviews and recommendations, Surviving the Future, TEQs (Tradable Energy Quotas)

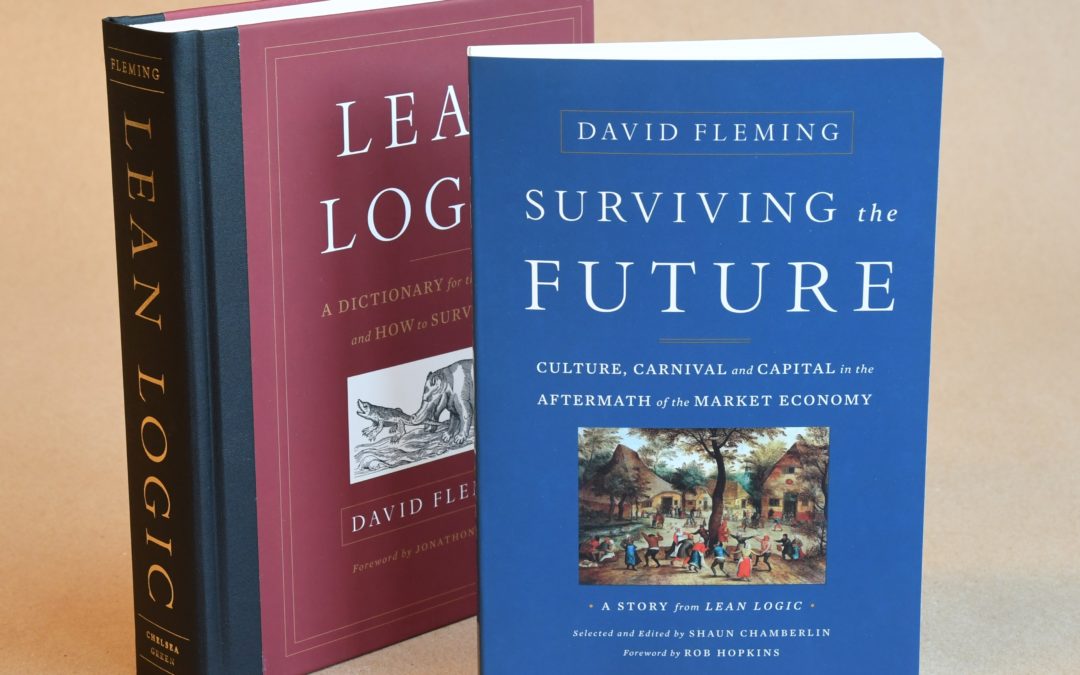

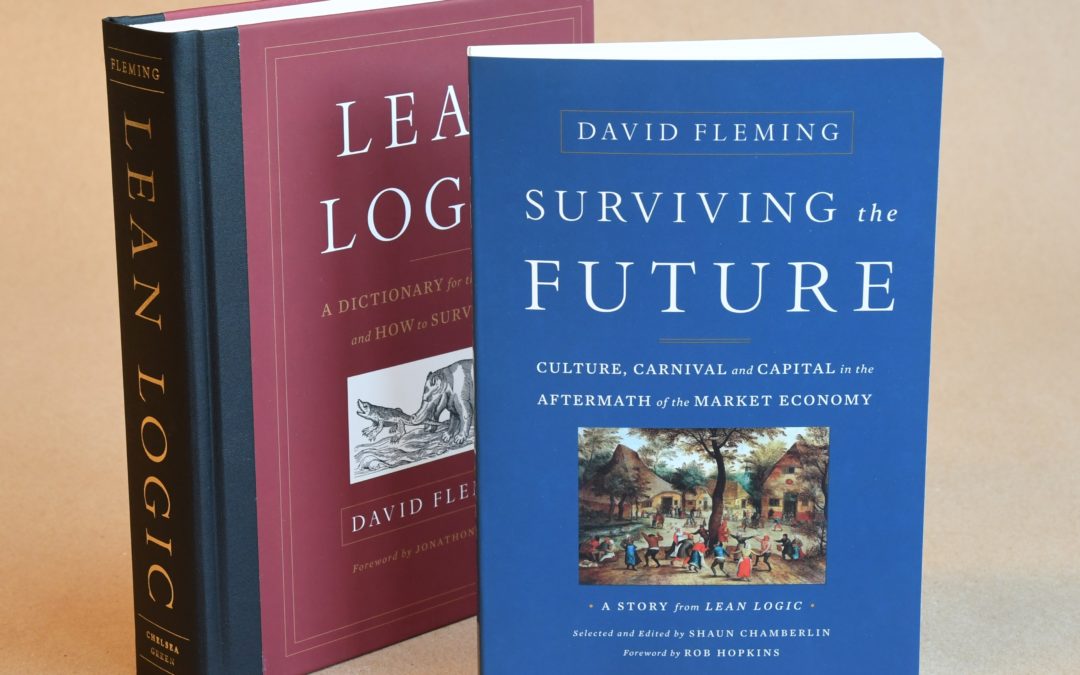

Last week the wonderful Brianne Goodspeed of Chelsea Green Publishing interviewed me on my late mentor David Fleming and the astonishing gift he left to the world. His sudden death in 2010 left behind his great unpublished work—Lean Logic: A Dictionary for the Future...

by Shaun Chamberlin | May 19, 2014 | All Posts, Cultural stories, Economics, Philosophy, Transition Movement

This post was originally written by me as a guest post for Rob Hopkins’ Transition Culture blog, but I have kindly given myself permission to reproduce it here ? A response to a recent post by Rob Hopkins ‘The impact of Transition. In numbers.’....

by Shaun Chamberlin | Nov 20, 2012 | All Posts, Cultural stories, Economics, Favourite posts, Politics, The right to land

The right to access land matters, in a fundamental way. It is a place to live, a source for food, for water, for fuel, and for sustenance of almost every kind. And land management also has profound impacts on our ecosystems and environment, and thus on our well-being...

by Shaun Chamberlin | May 17, 2012 | All Posts, Cultural stories, David Fleming, Economics, Favourite posts, Politics, The Transition Timeline, Transition Movement

Last month I was one of forty or so attendees of the Transition ‘Peak Money’ day. It was a fascinating collection of people, from theorists to activists, and a potent opportunity to reflect on the challenges facing us all as the glaring errors at the heart...

by Shaun Chamberlin | May 2, 2012 | All Posts, Cultural stories, Transition Movement

I’ll be heading down to Transition Heathrow from this Monday 7th May – Sunday 13th May to help them in the building of a new community longhouse from reclaimed materials. It should be great fun, a real education, and a chance to contribute to a Transition...

Recent Comments