by Shaun Chamberlin | May 19, 2014 | All Posts, Cultural stories, Economics, Philosophy, Transition Movement

This post was originally written by me as a guest post for Rob Hopkins’ Transition Culture blog, but I have kindly given myself permission to reproduce it here ? A response to a recent post by Rob Hopkins ‘The impact of Transition. In numbers.’....

by Shaun Chamberlin | Dec 13, 2008 | All Posts, Cultural stories, Philosophy, The Transition Timeline, Transition Movement

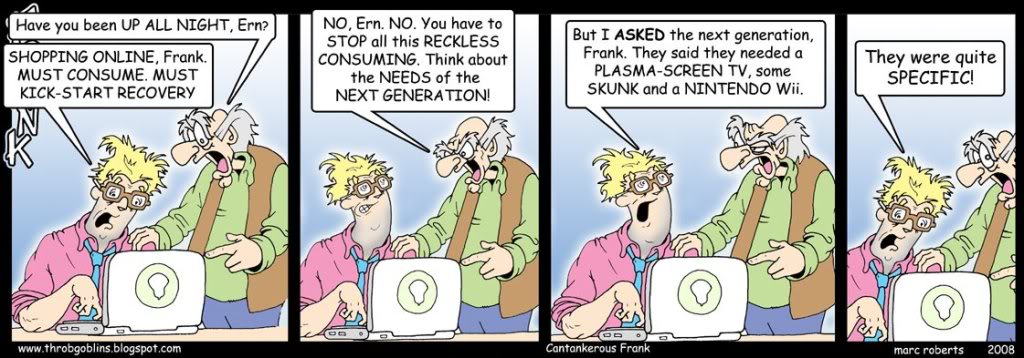

“A person will worship something, have no doubt about that. We may think our tribute is paid in secret in the dark recesses of our hearts, but it will out. That which dominates our imaginations and our thoughts will determine our lives, and our character....

by Shaun Chamberlin | Jun 29, 2008 | All Posts, Climate Change, Cultural stories, Favourite posts, Peak Oil, Philosophy, Reviews and recommendations, TEQs (Tradable Energy Quotas), Transition Movement

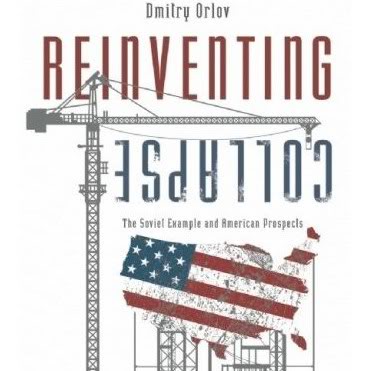

As George Carlin once said, “they call it the American dream because you have to be asleep to believe in it”. At the risk of this blog becoming ‘review corner’, that seems the perfect introduction to the book I just finished reading — Dmitry...

Recent Comments