Deep solidarity

Sometimes, like Kant, I’m moved to write by reading something I so profoundly disagree with. Tonight, curiously, I’m moved by a wish for a little less disagreement. Reading Jeremy Lent’s excellent post What Will You Say To Your Grandchildren? and...

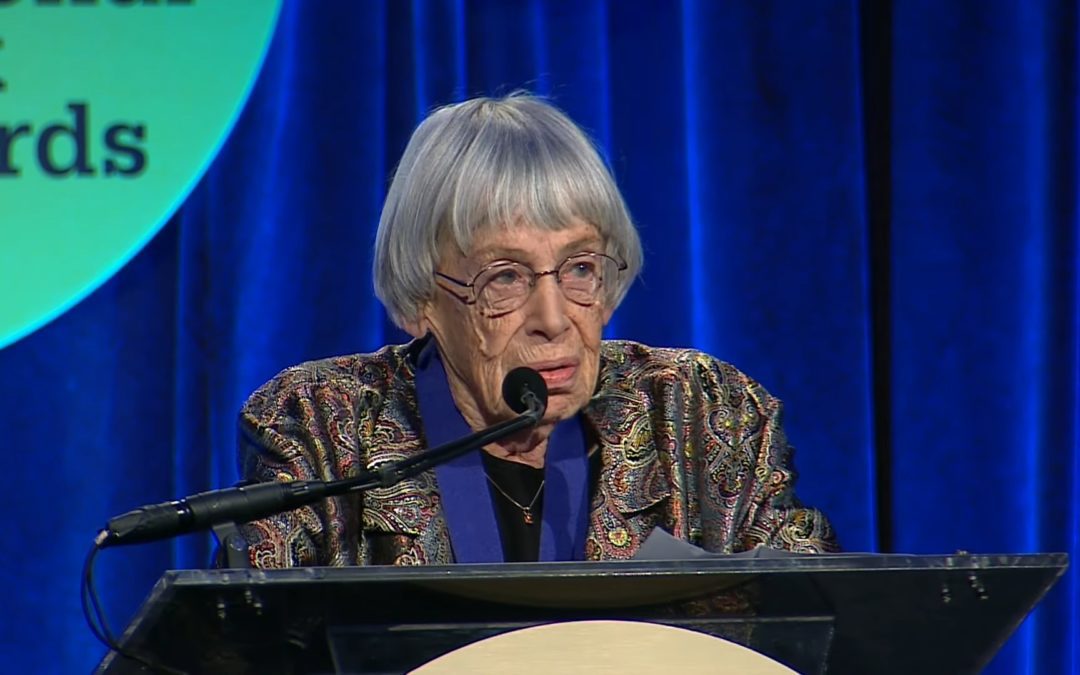

Realists of a larger reality

In 2014 Ursula K. Le Guin accepted the Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters with a deliciously powerful speech. Aware that her time was nearing its end, she declared that her “beautiful reward” was accepted on behalf of, and shared with...

The Sequel: Life After Economic Growth

Originally published in the Fall 2018 edition of Tikkun

As Simon Mont wrote in Tikkun’s recent issue on the New Economy, “capitalism is collapsing under the weight of itself, and it’s not pretty.”[i]

Our globalised world finds itself caught on the horns of a seemingly impossible dilemma — either cease growing, and so collapse the economy on which we all depend, or continue to grow until we overwhelm and destroy the ecosystems on which we all depend.

As my late mentor, the historian and economist David Fleming, put it,[ii]

Why I’m Rebelling against Extinction (wait, should that really need explaining..?)

I got arrested for the first time in my life this week. And I’m proud of it. As long-time followers of this blog know, over the past 13 years I’ve tried everything I know to get our society to change its omnicidal course. I’ve written books,...

Recent Comments