Originally published in the Fall 2018 edition of Tikkun

As Simon Mont wrote in Tikkun’s recent issue on the New Economy, “capitalism is collapsing under the weight of itself, and it’s not pretty.”[i]

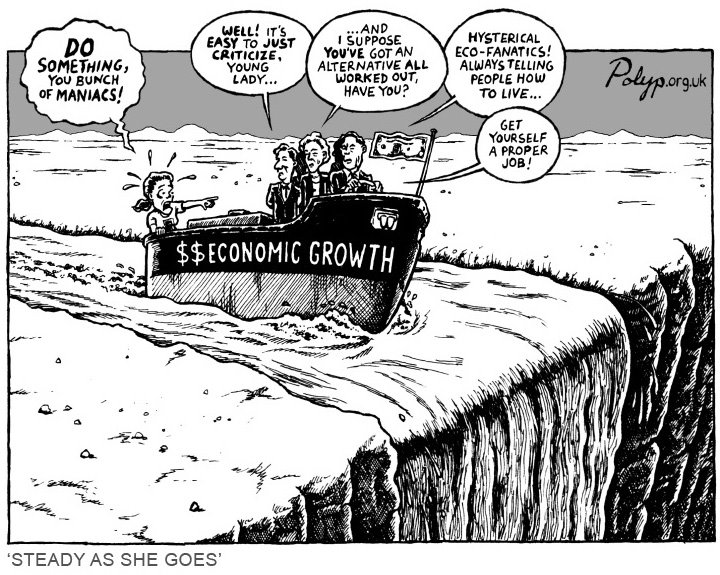

Our globalised world finds itself caught on the horns of a seemingly impossible dilemma — either cease growing, and so collapse the economy on which we all depend, or continue to grow until we overwhelm and destroy the ecosystems on which we all depend.

As my late mentor, the historian and economist David Fleming, put it,[ii]

It is certain that there are no simple answers to this — none that could be proposed without proposing at the same time a transformation in the whole of the way we think, work and order our lives.

And yet, faced with this fundamental systemic conundrum, our leaders hold tight to their simple answer — growth. Having worked supporting people with drug addiction for several years, it is hard to escape the parallels to the more tragic cases. The dire consequences of our choices are piling ever higher around us, threatening the very continuation of our lives and those around us. And the response is to double down on the current path and turn a blind eye — to sink deeper into denial. It is just too difficult, too brave, to undergo that dark night of the soul — to admit the problem, to seek a new paradigm.

So we hear it over and over — we must keep growth high, keep unemployment low. Donald Trump’s recent Twitter boast that U.S. GDP growth (4.2%) was higher than unemployment (3.9%) for the first time in over a century was both inaccurate and bizarre, but it betrays his allegiance to these numbers.

And of course, he is far from alone. All his peers are junkies too. Most people — even most economists — never question the desirability of these measures, as if mastery of them could somehow heal an economy so violently contrary to our human instincts and desires that it leaves epidemics of depression, loneliness and suicide everywhere it goes. That sparks not only economic and environmental devastation, but cultural and spiritual annihilation.

As if there were not something deeper, something larger, going on here…

So let’s step back for a minute. First, “keep unemployment low”. The appeal is easy to see, but what’s really going on here?

Consider the great economist John Maynard Keynes’ prediction, in 1930, that by the year 2000 the onward march of technology would lead to an average 15 hour working week in countries like the U.S. and U.K. Naturally he saw this as progress — not a doom-laden prophecy of mass unemployment — and this fact begins to expose the inherent contradiction in the aim of maximising employment. What economists see as wastefully underutilised ‘spare labour’ is what most of us might call spare time — time enjoyed outside the formal economy — a welcome part of a life well lived rather than a ‘problem of unemployment.’[iii]

Of course, modern life is not noted for the utopian, leisurely daily routines enjoyed by the bulk of the population. So why was Keynes wrong? Certainly not because the rate of technological advance over the past century failed to live up to his expectations. No, rather because our economic paradigm literally makes widely-shared leisure time impossible.

To see why, Fleming invites us to take a further step back. He notes the startlingly extensive holidays (five months of each year, in some places) achieved in medieval Europe. How were the good folk of the Middle Ages able to enjoy so much more leisure time than we are in our technologically-advanced society? He explains,[iv]

In a competitive market economy a large amount of roughly equally-shared leisure time — say, a three-day working week, or less — is hard to sustain, because anyone who decides to instead work a full week can produce for a lower price (working longer hours lets them produce more, and thus earn the same wage while selling each item or service more cheaply).

These more competitive people would then be fully employed, and would put the more leisurely out of business completely.

This is what puts the grim into reality.

So in an economy like ours, a technological advance that doubles the amount of useful work a person can do in a day becomes a problem rather than a benefit. It tends to put half the workers out of work, turning them into a potential drain on the state (or simply leaving them destitute).

In theory all the workers could just work half-time and still produce all that is needed, as Keynes predicted, and as is promised all over again by today’s latest wave of automation techno-utopians.[v] But in practice workers are often afraid of having their pay cut, or losing their jobs to a stranger who is willing to work longer hours. In the absence of a sense of community or mutual trust, and having been taught to seek their security in a wage, people instead compete against each other for the right to perform the pointless tasks that anthropologist David Graeber memorably characterised as “bullshit jobs.”[vi]

Meanwhile, governments see that the only way to keep unemployment from rising to the point where the system breaks down is through endless economic growth, which thus becomes a non-negotiable obligation — a dogma. Ah, here’s our second simple imperative, “keep growth high”…

The problem here is elementary, brutal maths. Economists tell us that 2-3% growth annually, give or take, is necessary to avoid recession or depression. Arithmetic tells us that if something grows at 2% a year, it will double in size in 35 years. At 3% a year it will double in 24 years. At Trump’s claimed 4.2%..? 17 years.

Can we seriously imagine our world in just two or three decades with twice the economic activity — twice the oil extraction, twice the intensive agriculture, twice the manufacturing, twice the pollution? And then in two or three more decades doubling again, to four times the size of today’s economy… Even superabundance like that of the natural world cannot indefinitely support an exponentially growing parasite.[vii]

It’s a remarkably straightforward point; just arithmetic. And yet it remains respected mainstream opinion that we should just keep growing, quietly crossing our fingers that somehow Nature — the economy upon which all others depend — will defy both physics and maths and continue to bail us out forever. As Fleming put it,[viii]

Civilisations self-destruct anyway, but it is reasonable to ask whether they have done so before with such enthusiasm, in obedience to such an acutely absurd superstition, while claiming with such insistence that they were beyond being seduced by the irrational promises of religion.

In this context, then, it’s no surprise to be hearing increasingly shrill, desperate alarm from scientists around the world as they observe the natural world crumbling under the impossible, ever-growing pressure. As I write, the latest report announced that 60% of mammals, birds, fish and reptiles have been annihilated since 1970. Put starkly, most of the wild nature that was here fifty years ago is gone. And still we seek to grow the human economy, and cheer when that growth accelerates.[ix]

Similarly, the inherently conservative Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released their Global Warming of 1.5ºC report, which makes it abundantly clear that the unfolding physical realities studied by climate science are dramatically outpacing the policies notionally intended to address them. They find that we must halve emissions in the next twelve years, and so feel forced to call for “rapid and far-reaching … unprecedented” transformation in the economy.[x]

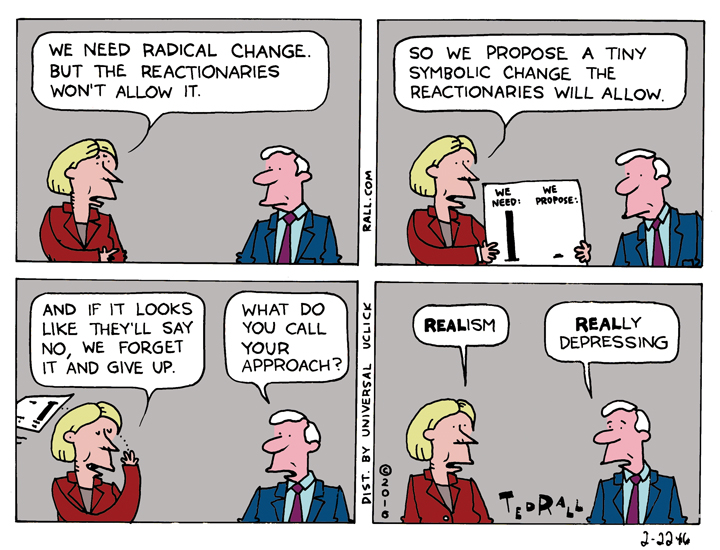

Hence it has become impossible to be simultaneously realistic about both the political climate and the science of climate. The two stubbornly refuse to reconcile, so we are forced to decide which carries more weight, and then be profoundly unrealistic about the other.

To take present policy seriously demands a total rejection of the science. To take the science seriously demands a total rejection of the policy on the table. And so grassroots movements like the Extinction Rebellion and Climate Mobilization are emerging — the realists of a larger reality.

They recognise that the dominant politico-economic paradigm leads to nothing but a literal dead end. We are on the cusp of a fundamental shift, for better or worse — either we change direction or we end up where we are headed.

It’s interesting then that a change of direction is exactly what electorates have been voting for, or at least trying to. Globalisation and neoliberalism are not only destroying our collective future, but have also all-but-destroyed the present for many, as the neofeudalism termed ‘austerity’ continues to bite. The common factor behind unexpected election results like Trump in the US, Brexit and Corbyn in the UK and Bolsonaro in Brazil appears to be desperate rejection of the establishment and the status quo.

Unfortunately, in such times, when more and more people are struggling to support their families, and losing faith in the dominant stories of what is important, the far right has a track record of providing simple answers. It is important to remember that fascists like Mussolini and Hitler didn’t only consolidate power on the basis of lies and fear — they also raised wages, addressed unemployment and improved working conditions.

To effectively challenge the drift into fascism, then, we need to present an alternative politico-economic vision that can restore identity, pride and economic well-being. We need to tell a beautiful story of how we will make the future better for the desperate, rather than a fearful one. To provide a grounded, compelling alternative to a future I have no desire to live through.

This is what Fleming devoted his life to developing. Fifty years ago he saw the central dilemma of our times approaching, and devoted his life to facing the inevitable question — what might a life-sustaining, nourishing economy look like, after the impending end of economic growth.

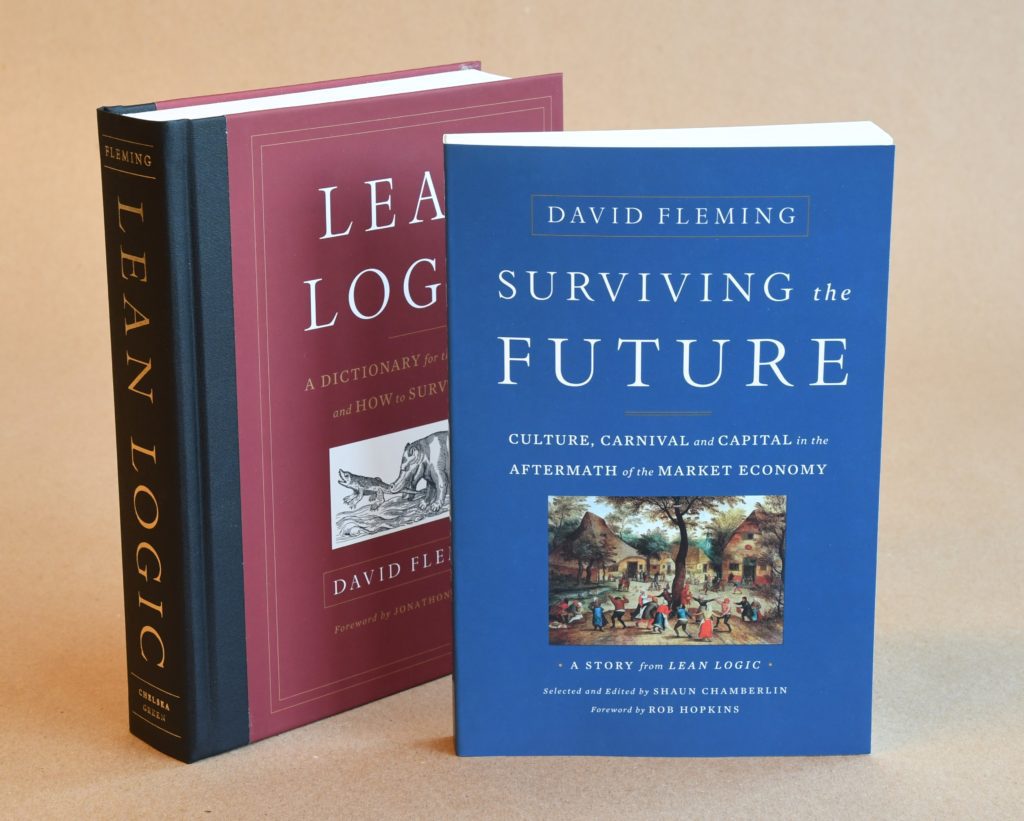

This culminated in his posthumous 2016 book Surviving the Future: Culture, Carnival and Capital in the Aftermath of the Market Economy.

Therein, he reminds us of just how unusual today’s ‘ordinary’ is, and how profoundly unrealistic it is to pin our hopes on market capitalism — an economic system that has existed for less than 1% of recorded history and is already not only destroying its own foundations, but those of life on Earth. In his words,[xi]

The Great Transformation has already happened.

It was the revolution in politics, economics and society that came with the market economy, and which hit its stride in Britain in the late eighteenth century.

Most of human history had been bred, fed and watered by another sort of economy, but the market has replaced, as far as possible, the social capital of reciprocal obligation, loyalties, authority structures, culture and traditions with exchange, price and the impersonal principles of economics.

This historical context is critical. The New Economy that we need is, in many ways, the Old Economy.

It is time to rediscover the ways human beings related to each other for hundreds of thousands of years before we were ripped into isolation by the brief historical anomaly of market capitalism, into which all of us alive today happened to be born.

As Mont put it,[xii]

[The New Economy] is a groundswell to relying on a memory harbored in our hearts to make real a vision of humans returning to deep relationships with earth, spirit, and each other, that is constantly evolving and changing, while staying acutely cognizant of the fact that we must relearn how to keep ourselves alive without capitalism and extraction.

Fleming took that dear memory harbored in our hearts and wrote it large across the page. “We know what we need to do,” he writes, “We need to build the sequel, to draw on inspiration which has lain dormant, like the seed beneath the snow.”

His sparkling, tantalising writing has become a touch-stone for thousands of communities around the world who are putting it into practice, with his startling seven-point protocol for an economics based in trust, loyalty and local diversity one of the key factors in the birth of the now-global Transition Towns movement.

Drawing on the work of the likes of Edgar Cahn, Fleming provides the radical but historically-proven sequel to today’s capitalism: focusing neither on the growth nor de-growth of the market economy, but on huge expansion of the ‘informal’ or non-monetary economy — the ‘core economy’ that keeps our society alive, even today. This is the economy of what we love: of the things we naturally do when not otherwise compelled, of music, play, family, volunteering, activism, friendship and home.

Refreshingly — uniquely perhaps, among modern economists — he argues that the key to sustaining a post-growth economy is culture and community. Those extensive holidays of former times were far from a product of laziness. Rather they were, in an important sense, what men and women lived for. ‘Spare time’ spent in feasting, performing, collaborating and merrymaking together formed the basis of communal bonding, membership and trust. As one of his readers put it — when productivity improves, “in our system you have a problem; in Fleming’s system you have a party”.

These shared cultural ties then bind people together in cooperation, support and solidarity, the essential foundations for the communities which have thrived throughout history in the absence of economic growth or full-time employment. As Fleming writes,[xiii]

The [future] economy will depend for its existence on a deep foundation in culture.

It is possible to live without it, but only for a time, like holding your breath under water.

This is a key lesson for our organising and our community work. With its rare blend of charm and rigour, Fleming’s writing reminds us that nurturing the core economy back to health — getting to know people, enjoying time together and helping to provide for each other’s basic needs — is not merely some quaint and obsolete shared longing, but an absolute practical priority.

Over the past couple of centuries, this core economy has been much weakened, as the ever-growing stresses of precarious employment and rising prices have left people with less time and energy for friends, family and fun. But as we in communities around the world spend our days relearning how to seek our security in each other rather than in money, we notice that the unfolding collapse of the omnicidal growth economy becomes less something to fear, and more something to celebrate.

We think less about what we might stand to lose and far more about the joys we had already lost and are slowly learning to regain, together. At long last we are remembering how to build a world in which, as David put it, “there will be time for music.”

__

Shaun Chamberlin authored the Transition movement’s second book, The Transition Timeline, and has served as both chair of the Ecological Land Co-operative and a director of Global Justice Now. He is the executive producer of 2020 film The Sequel: What Will Follow Our Troubled Civilisation? and editor of several books, including David Fleming’s posthumous Lean Logic and Surviving the Future.

[i] Mont, S. (2018). Introduction to the next economy. Tikkun, Volume 33, Number 3:16-17.

[ii] Fleming, D. (2016). Surviving the Future: Culture, Carnival and Capital in the Aftermath of the Market Economy (p. 129). White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing.

[iii] Keynes, J. M. (1930). Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren. Available at: http://www.econ.yale.edu/smith/econ116a/keynes1.pdf

[iv] Fleming, D. (2016). Surviving the Future: Culture, Carnival and Capital in the Aftermath of the Market Economy (p. 75). White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing.

[v] These claims have a long history. The Democratic Review, impressed by the new technologies, predicted in 1853 that by 1900, “men and women will then have no harassing cares or laborious duties to fulfil. Machinery will perform all work — automata will direct them. The only task of the human race will be to make love, study and be happy”.

[vi] Graeber, D. (2013). On the Phenomenon of Bullshit Jobs: A Work Rant. STRIKE!, Issue 3. Available at: http://strikemag.org/bullshit-jobs

[vii] In the words of Prof. Albert Bartlett, “The greatest shortcoming of the human race is our inability to understand the exponential function.” His legendary ‘Arithmetic, Population and Energy’ lecture is one of the most important ever recorded and widely available online, e.g. at: https://www.albartlett.org/presentations/arithmetic_population_energy.html

[viii] Fleming, D. (2016). Surviving the Future: Culture, Carnival and Capital in the Aftermath of the Market Economy (p. 180). White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing.

[ix] WWF (2018). Living Planet Report – 2018: Aiming Higher. Grooten, M. and Almond, R.E.A. (Eds). Gland, Switzerland.

[x] IPCC (2018). Global Warming of 1.5ºC, Summary for Policymakers (p.21). Available at: http://report.ipcc.ch/sr15/pdf/sr15_spm_final.pdf

[xi] Fleming, D. (2016). Surviving the Future: Culture, Carnival and Capital in the Aftermath of the Market Economy (p. 179). White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing.

[xii] Mont, S. (2018). Introduction to the next economy. Tikkun, Volume 33, Number 3:16-17.

[xiii] Fleming, D. (2016). Surviving the Future: Culture, Carnival and Capital in the Aftermath of the Market Economy (p. 40). White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing.