by Shaun Chamberlin | Nov 4, 2022 | All Posts, Articles

Originally written as my contribution to the Jihlava Inspiration Forum book, October 2022

The following is my response to the invitation for a brief 1,000 word reflection on the topic:

"How should we transform our relationships for the future? And what can each of us do about it?"

Transforming our relationship ~with~ the future

"The crisis we face is fundamentally one of relating"

The more deeply I reflect on these words from the extraordinary Eve Annecke, the more truth they reveal.

And indeed, useful truth… of that special kind that opens real, practical paths for transforming our future. [i]

That said, I must be clear.

My own dark optimism does not permit me to convey the popular idea that our future can be “anything we dream”; nor even that it will be bright, at least in any common sense of the word. Quite to the contrary, our time is one of lessons long ignored coming back to bite.

Our time is one in which the common assumption that our children will be better off than us has already quietly reversed. One in which the hard consequences to hubris come starkly into view, even as we stubbornly insist that our destiny is off-world, exploring the stars...

by Shaun Chamberlin | Apr 30, 2020 | All Posts, Articles

Originally published in the Spring 2020 edition of STIR magazine

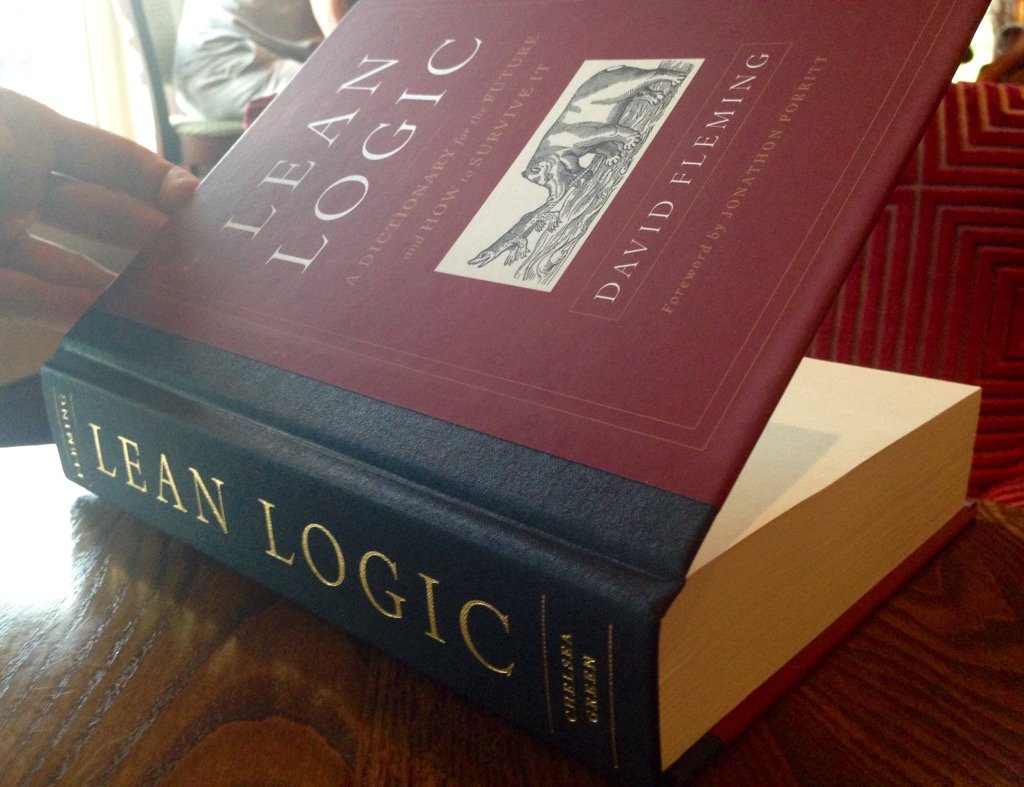

Extracts from David Fleming's extraordinary, posthumous Lean Logic: A Dictionary for the Future and How to Survive It (Chelsea Green, 2016). Selected for this issue by its editor Shaun Chamberlin. Endnotes omitted.

Asterisks mark words with their own separate entry in the dictionary. Any of these can be read in full and for free at the newly-launched LeanLogic.online

Expectations. The attitudes and assumptions which shape the way we make sense of events and plan our response. Unless our expectations are right, or at least expressed as a considered set of probabilities, we plan to fail. But, right or wrong, expectations are self-reinforcing, for we see what we expect to see. We may not realise how critical expectations are in guiding perception, but they are decisive. In the context of our perception of *art, the art historian E.H. Gombrich reminds us of . . .

by Shaun Chamberlin | Nov 30, 2018 | All Posts, Articles

Originally published in the Fall 2018 edition of Tikkun

As Simon Mont wrote in Tikkun’s recent issue on the New Economy, “capitalism is collapsing under the weight of itself, and it’s not pretty.”[i]

Our globalised world finds itself caught on the horns of a seemingly impossible dilemma — either cease growing, and so collapse the economy on which we all depend, or continue to grow until we overwhelm and destroy the ecosystems on which we all depend.

As my late mentor, the historian and economist David Fleming, put it,[ii]

by Shaun Chamberlin | Nov 30, 2016 | All Posts, Articles

Originally published in the Fall/Winter 2016 edition of the Kosmos journal

I confess — I love Magnum ice creams!

Yet surely as a good, responsible eco-citizen, I must be aware that these relatively cheap, beautifully packaged nuggets of deliciousness are inescapably products of the industrial system that is destroying all that I hold dear?

That Magnums are produced by Unilever, not only the world's biggest ice cream manufacturer but the world's third largest multinational consumer goods company, associated with deforestation for palm oil, exploitation of workers, the promotion of unsustainable agriculture, factory farming, the use of tax havens, lobbying against GM labelling and so on...

I don't mean to imply that they're the worst offenders. It's just that I happen to particularly enjoy their product (despite being aware that there's no actual cream in it). For me, it's what Unilever's marketing team would doubtless term a 'wicked indulgence.'

So I should stop eating them, right? I should overcome my baser urges and live a lifestyle that accords with my values and beliefs?

Well, there is certainly an argument for that, and I know many friends who struggle and expend huge energy and willpower on resisting their deep desire for Magnums, or bacon, or jet flights or whatever... And even feel resentment towards those who don't do the same.

Occasionally, of course, they give in and then feel huge guilt, and maybe greater ill will towards those who seem to consume without even feeling this inner conflict.

With this approach, it is little wonder that we environmentalists are often characterised as tedious killjoys who wouldn't know how to enjoy ourselves in a vegan chocolate factory. Perhaps it is even fair. After all, there is nothing inspiring about the struggles of a divided and conflicted self. And there is nothing less inspiring than 'shoulds.' With the possible exception of 'should nots'...

by Shaun Chamberlin | Oct 26, 2016 | All Posts, Articles

Originally published on openDemocracy on 26 October 2016

The original article can be found here

Economics shapes the bulk of our waking hours, so how do we reclaim control of our lives from such a dismal science?

As my friend David Fleming once wrote, conventional economics 'puts the grim into reality'.

Something of a radical, back in the 1970s Fleming was involved in the early days of what is now the Green Party of England and Wales. Frustrated by the mainstream's limited engagement with ecological thinking, he urged his peers to learn the language and concepts of economics in order to confound the arguments of their opponents.

by Shaun Chamberlin | Apr 16, 2015 | All Posts, Articles

Originally published in the Carbon Management peer-reviewed journal on 16th April 2015

The formal version of record can be found here

This is the Abstract, Executive Summary and Introduction of the paper. Full text available here.

Reconciling scientific reality with realpolitik: moving beyond carbon pricing to TEQs – an integrated, economy-wide emissions cap

Abstract

This article considers why price-based frameworks may be inherently unsuitable for delivering unprecedented global emissions reductions while retaining the necessary public and political support, and argues that it is time to instead draw on quantity-based mechanisms such as TEQs (Tradable Energy Quotas).

TEQs is a climate policy framework combining a hard cap on emissions with the use of market mechanisms to distribute quotas beneath that cap.

Recent Comments