by Shaun Chamberlin | Nov 30, 2014 | All Posts, Articles

Originally published as the editorial of the Fall/Winter 2014 edition of the Kosmos journal

The online version of the editorial can be found here

If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together. And if you want to transform…?

Sometimes we meet a young person who continues to hold a deep place in our minds and hearts long afterwards. I met Shaun briefly at the New Story Summit. It felt as though I had known him forever. The future of humanity and the hope of the world is with such talented and dedicated youth. I want to honor his work by sharing one of his essays.

~ Nancy Roof, editor, Kosmos journal

by Shaun Chamberlin | Jan 31, 2013 | All Posts, Articles

Originally published in the Winter 2012 issue of Permaculture magazine; that article can be found here

The below extended version republished in the Jan 2013 issue of Country Smallholding. Full illustrated feature (including comment pieces from others) available here. The magazine's editorial also concerned itself with the topics raised

And the Spring 2015 issue of STIR magazine featured an updated version, taking a different slant, which can be found here

An imaginative and exciting scheme was launched to provide would-be smallholders with affordable land and low-impact dwellings. But then it was blocked by a local council, and has now gone to appeal. The story highlights how our planning process can frustrate so many 'good life' dreams. Shaun Chamberlin, who helped launch the scheme, explains

Nearly half of the UK's land is owned by just 40,000 people (0.06% of the population).1 For those Country Smallholding readers only too familiar with the difficulties in securing affordable access to land, this will not be a comforting statistic.

by Shaun Chamberlin | Jun 30, 2012 | All Posts, Articles

"What ties everything together and makes meaning are our cultural stories. For the book I talked to hundreds of people and found that the dominant narratives of our future fell into three categories: business as usual (nothing really changes), doom of one kind of another (our time is up) and the myth of progress (we are the most advanced society ever known and our manifest destiny leads to some perfect Star Trek future).

"It's easy to see why people are most drawn to this last story, Technotopia. The problem is the reality doesn't bear it out. This Most Advanced Culture Ever has higher levels of depression and inequality than ever and is destroying the ecological systems that support everything that is alive on the planet, so it's hard to justify the idea we are moving towards a better future.

"So we thought what we needed was another positive narrative about the future which is just as embedded as the other stories in our everyday culture, but one that reflects scientific evidence and the reality of what is happening in our world. A Transition vision. That's what the book is about."

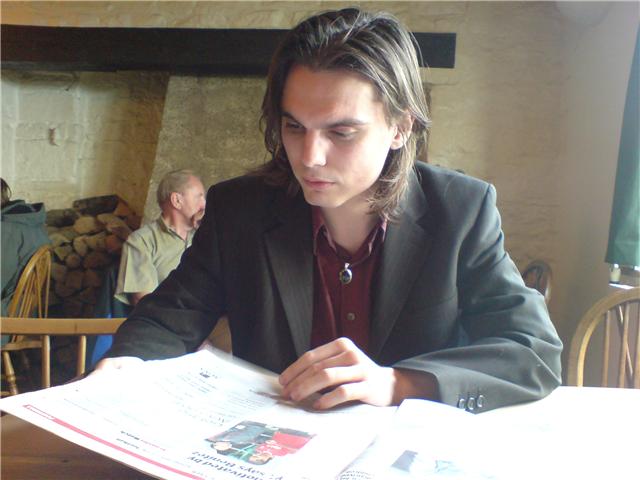

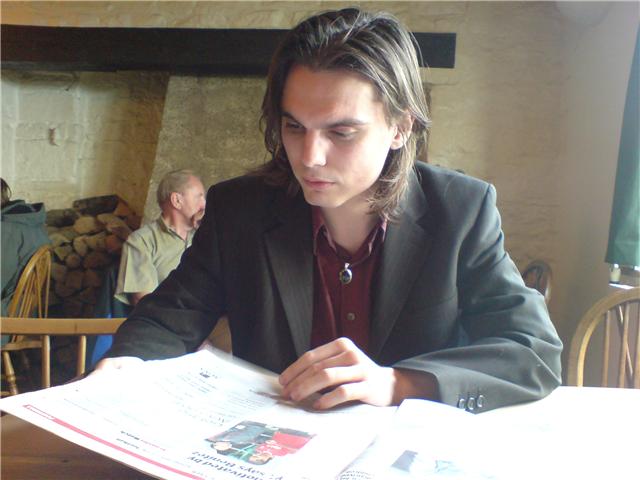

Much of Shaun's own story is set within this fourth narrative. As well as co-founding Transition Town Kingston (TTK), he has contributed chapters to several books, served as an advisor to the Department of Energy and Climate Change, co-authored the latest report from the All Party Parliamentary Group on Peak Oil and Gas, and helped both edit Mark Boyle's upcoming The Moneyless Manifesto and bring David Fleming's encyclopedic Lean Logic into print.

Fleming also invented a system known as Tradable Energy Quotas (TEQs), a rationing scheme that works to ensure energy for all in times of scarcity. Subtle and clever in its design, Shaun explained, but easy to use (much like an Oyster card).

by Shaun Chamberlin | Jan 24, 2011 | All Posts, Articles

APPGOPO's endorsement of TEQs comes at an interesting time in the rationing system's progress towards political acceptability. The inventor of TEQs, Dr. David Fleming (who passed away in November 2010), was a close friend of ASPO's Colin Campbell and one of the early whistleblowers on peak oil, and designed TEQs explicitly to address peak oil as well as climate change. He first published on the system in 1996, but its profile has grown in tandem with that of the challenges it was designed to address.

TEQs first received a Ten Minute Rule Bill reading at Parliament in 2004, before extensive interest from research centres led to a Government-funded scoping study in 2006. This reached positive conclusions, and was followed by expressions of interest from successive Secretaries of State for the Environment.

Accordingly, the Government commissioned a pre-feasibility study into the system, which concluded in May 2008. The headline finding of this was that TEQs "has potential to engage individuals in taking action to combat climate change, but is essentially ahead of its time and expected costs for implementation are high... The Government remains interested in the concept and, although it will not be continuing its research programme at this stage, it will monitor the wealth of research focusing on this area and may introduce (TEQs) if the value of savings and cost implications change".

The new APPGOPO report pulls together an impressive range of research to demonstrate conclusively that this condition has now been met, with bodies such as the Institute for Public Policy Research, the Lean Economy Connection, the Centre for Sustainable Energy and the UK Parliament's own Environmental Audit Committee all having criticised the pre-feasibility study's methodology and the decision to delay further moves towards implementation. One of the key criticisms is that the pre-feasibility study's cost-benefit analysis was overly focused on carbon emissions, and entirely failed to take into account the benefits of ensuring fair access to energy.

by Shaun Chamberlin | Dec 21, 2010 | All Posts, Articles

Originally published in The Ecologist on the 21st December 2010

The online version of the article can be found here

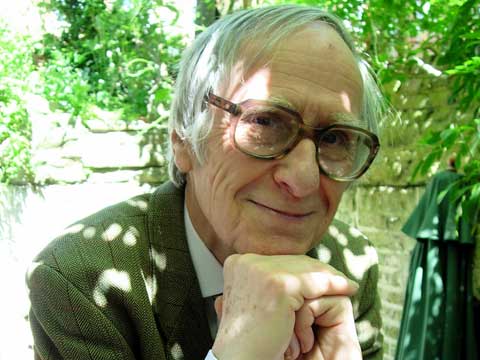

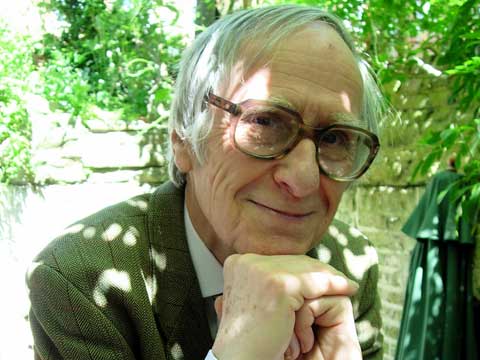

Dr. David Fleming, a visionary Green thinker and one of the key whistleblowers on peak oil, has died aged 70. He was a significant figure in the genesis of the UK Green Party, the New Economics Foundation and the Transition Towns movement. His legacy also includes TEQs (Tradable Energy Quotas), the energy rationing scheme currently under consideration by the UK Government, his influential book Lean Logic and the real delight and inspiration he gave so freely to all who met him.

David was born on the 2nd January 1940 at Chiddingfold, Surrey, to Norman Bell Beatie Fleming, a Harley Street eye surgeon, and Joan Margaret Fleming, an award-winning crime writer.

After reading History at Trinity College, Oxford from 1959 to 1963, he went on to work in manufacturing, marketing and financial PR before earning an MBA from Cranfield University in 1968.

Despite being an avowed Conservative voter, he was a significant figure in the development of the UK Ecology/Green Party — his flat in Hampstead serving as its party office in the late 70s and early 80s — and urged his contemporaries to learn the language and concepts of economics in order to confound the arguments of their opponents. He practiced what he preached, and in 1979 began studies in economics at Birkbeck College, University of London, completing an MSc in 1983 and his PhD in 1988.

by Shaun Chamberlin | Mar 31, 2010 | All Posts, Articles

Originally published in the March/April 2010 issue of Resurgence magazine

The online version of the article can be found here

Don't ask what the world needs. Ask what makes you come alive, and go do it.

For me, there was a definite moment when my environmental awakening began in earnest. I was studying philosophy at the University of York a decade ago when, out of the blue, I received an email from my father alerting me that “a long-term survey of oil and gas resources shows that demand for oil will exceed the maximum possible supply by 2010 and the oil price will sky-rocket”. This was followed by his (enduringly plausible) outline of the likely consequences – economic collapse, mass starvation and war.

I took a deep breath.

My initial reaction, like that of so many in their ‘peak oil moment’, was one of shock, rapidly followed by disbelief. I wondered how there could be near-universal silence on this issue if it truly had such vast implications, and tried to assure myself that ‘they’ would surely find some solution. Nonetheless, I resolved to look into it, partly in the hope of reassuring my father. Needless to say, what I learned wasn’t particularly reassuring.

As my studies came to an end, I quickly found myself with some appropriately philosophical questions to answer. The familiar post-university concerns of finding a way to earn some money, enjoying myself and caring for friends and family had to be balanced with two added factors – a sense that a ‘sound career path’ might not prove so sound in a civilisation that might be heading for the buffers, and an understanding that the world desperately needed all hands on deck if it was to have a future at all.

Recent Comments