by Shaun Chamberlin | Jun 30, 2009 | All Posts, Articles

Originally published in the Summer 2009 issue of Clean Slate - The Practical Journal of Sustainable Living

A PDF of the full illustrated article can be found here

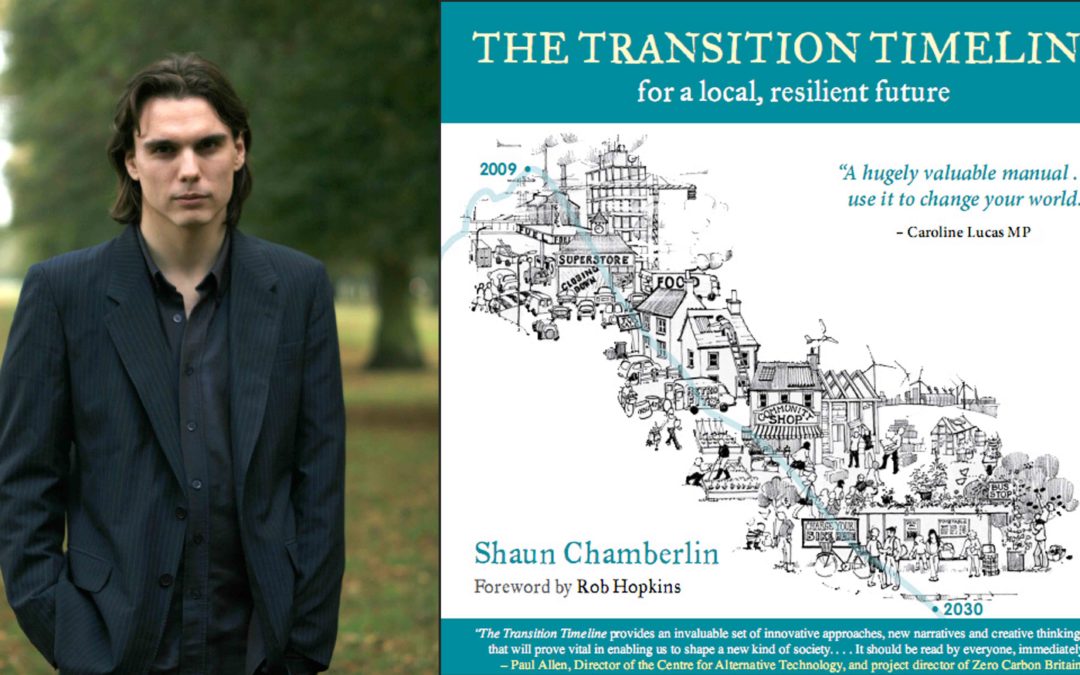

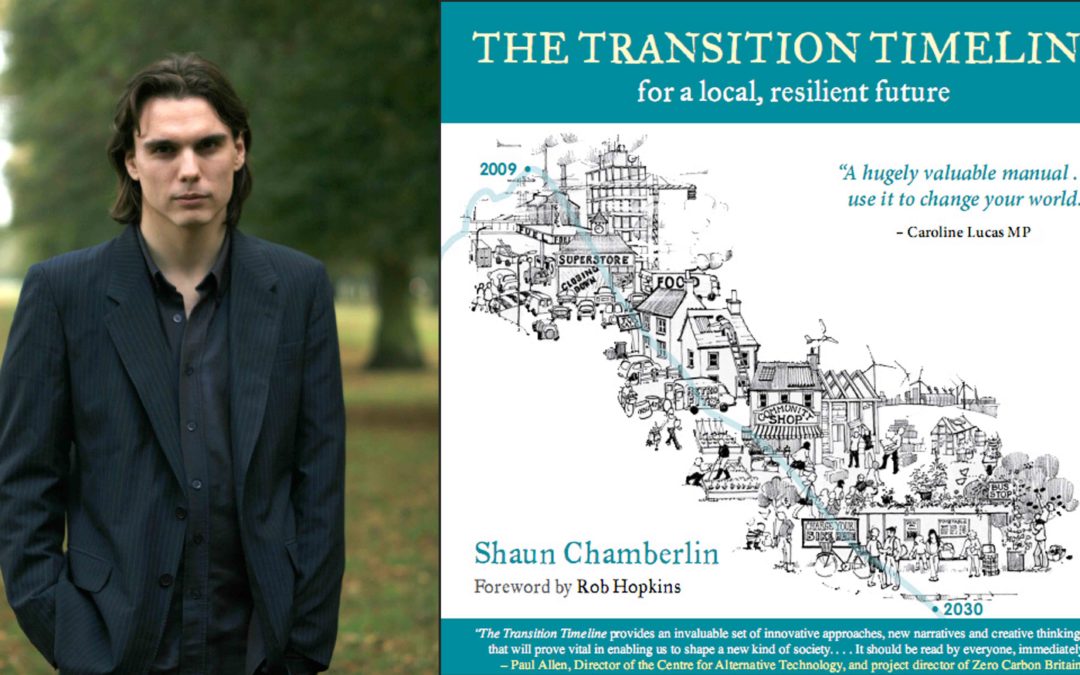

Blanche Cameron: What caused this book, The Transition Timeline, to come about?

Shaun Chamberlin: Primarily that Transition communities were asking for support. They were trying to form positive visions of the future for their communities, but were finding it a little foggy looking twenty years ahead, particularly with regard to the bigger trends and policy decisions around climate change, peak oil, food supply and the like. There was also a need to really make Transition's vision of a resilient, satisfying future as tangible and fleshed out as possible.

BC: You talk in the book about four stories of the future: Denial, Hitting the Wall, The Impossible Dream and The Transition Vision. Where do we find those narratives in the UK at the moment?

SC: A good example of 'Denial' would be most government planning documents. Apocalyptic 'Hitting the Wall' scenarios are seen in many films, such as the recent Age of Stupid, 'The Impossible Dream' might be Star Trek, with its unlimited technological fixes, and the Transition Vision...well, the closest existing analogy Rob Hopkins could come up with was Wallace and Gromit!

What we need is for this positive, realistic vision to find a central place in the popular mindset, to really get people out of bed in the morning. The Age of Stupid has done a great job of showing how bad things could become, but we also need to set out the desirable, practical alternatives. We want to see these ideas spreading into films, soap operas and throughout popular culture.

by Shaun Chamberlin | Mar 31, 2009 | All Posts, Articles

Originally published in the March/April 2009 issue of Resurgence magazine

A PDF of the full illustrated article can be found here

Ensuring essential entitlements to energy for all whilst guaranteeing that the UK meets

its target of 80% emissions reduction by 2050.

In these times of climate emergency, peak oil, economic turmoil and biodiversity devastation we are told again and again that large-scale problems require large-scale solutions - that we must channel our efforts into bigger, better global agreements to address these challenges.

As a young man searching for my calling in life I was being led in this direction until I attended the 'Life After Oil' course at Schumacher College and heard David Fleming utter a sentence that brought me up short:

"Large scale problems do not require large-scale solutions

- they require small-scale solutions within a large-scale framework."

At the time this was a radical new concept to me, but the more I considered it the more obvious it became, and the more it transformed my perspective. For example, I realised that while it is tempting to think of a tightening global cap on emissions as a solution in itself, such a cap is meaningless without on-the-ground solutions at the local and individual levels.

The true challenge lies not in the essential process of agreeing a cap, but in transforming our society so that it can thrive within this limit. If we fail in this, the pressure to loosen or abandon any cap will become irresistible - "enough talk of future generations, my children are hungry today".

So now that the UK Government (and President Obama) have agreed to an 80% emissions reduction by 2050 the focus must shift to implementing national frameworks that can engage communities in the transition to a lower-carbon society. At present the UK Government has over a hundred policies that impact on emissions levels but has produced, in the words of the Parliamentary Environmental Audit Committee,

by Shaun Chamberlin | Apr 5, 2007 | All Posts, Articles

Originally published at The Oil Drum: Europe on Apr 05, 2007

Reaction and comments on the article can be found here

The general consensus view on coal supplies has long been that we have hundreds of years of the stuff left, and that oil and gas depletion are the pressing concerns. However, dissenting voices are emerging. Canadian geologist David Hughes recently claimed that "peak coal looks like it's occurred in the Lower 48 (US states)", and the consensus position on coal is also called into serious question by the Coal: Resources and Future Production report just released by the Energy Watch Group in Germany. I present a summary of its findings here.

Reserves

The report highlights that the "proved reserves at year end" published in the most recent BP Statistical Review of World Energy in June 2006 are stated as being for year end 2005, but are actually based on the latest World Energy Council (WEC) assessments, which contain data for the end of 2002.

So our best figures on this are actually over four years old. And our worst figures? Well, some haven't been updated in 15 years (China) and some in up to 40 years (Vietnam, Afghanistan).

But really the key message in the global data lies in the rate at which reserves estimates have been revised downwards. As Peak Oilers well know, conventional wisdom has it that reserves will increase as more exploration takes place and prices rise. Yet, in truth, estimates for global coal resources have been consistently revised down, and by 55% over the past 25 years, from 10 trillion tons hce (hard coal equivalent) in 1980 to around 4.5 trillion tons hce in 2005. Certain countries (including Germany and the UK) have been revised down by over 90% in this period. The UK reported proved recoverable reserves of 45bn tons in WEC 1980, but these were continually revised downwards to reach only 0.22bn tons by the latest report. Cumulative UK production in this period amounted to only approx 1.8bn tons.

Recent Comments