Originally published as the editorial of the Fall/Winter 2014 edition of the Kosmos journal

The online version of the editorial can be found here

If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together. And if you want to transform…?

Sometimes we meet a young person who continues to hold a deep place in our minds and hearts long afterwards. I met Shaun briefly at the New Story Summit. It felt as though I had known him forever. The future of humanity and the hope of the world is with such talented and dedicated youth. I want to honor his work by sharing one of his essays.

~ Nancy Roof, editor, Kosmos journal

—

Like all the best tales, ours opens with music, and with Mark Kidel’s Resurgence article Conversation and Crossroads:

Some of the most powerful – and healing – forms of music combine strict ‘ways’ of doing things with free expression and the possibilities of interpretation or improvisation…

Wisdom and experience have suggested, in every corner of the world, that excessive self-expression is self-defeating and just as destructive as an over-zealous observance of rules and regulations. There is a need for a middle way which balances ‘hot’ and ‘cool’: the release of deep emotion with the articulacy and sophistication of formal aesthetic structures…

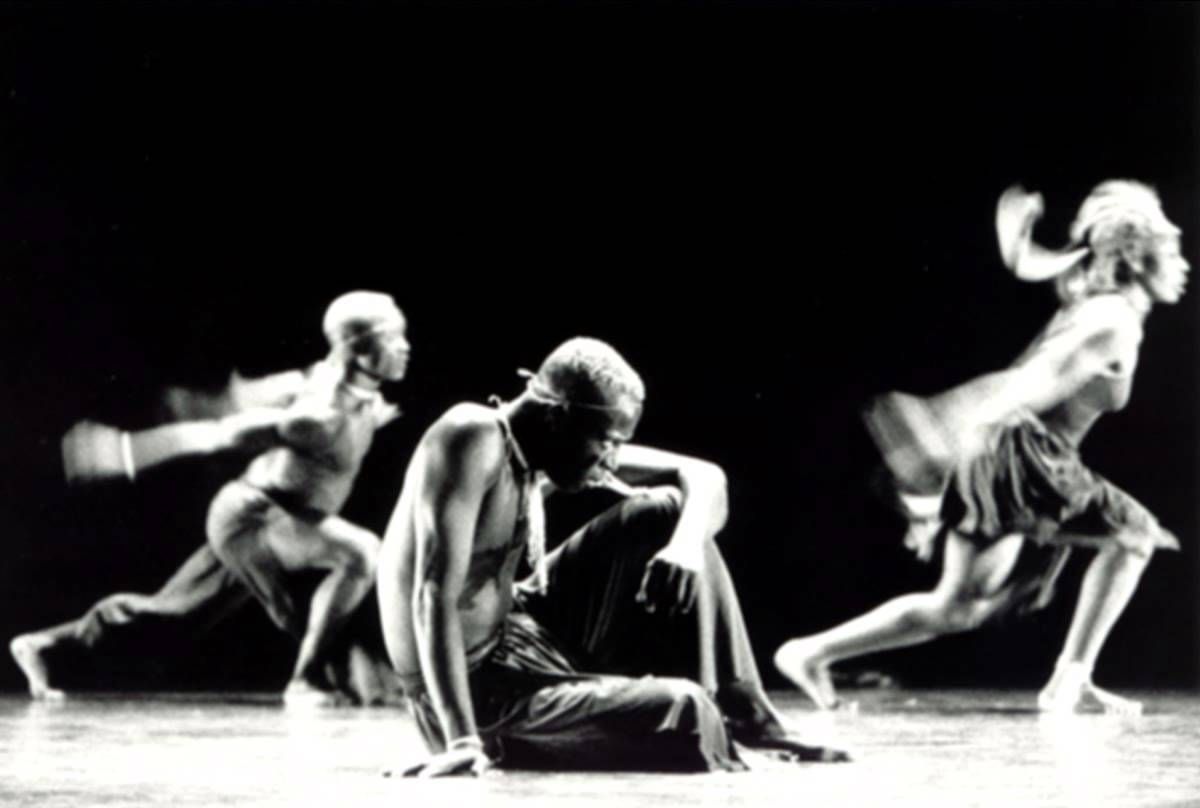

Whereas the enjoyment of pleasure was never frowned upon in the African context, it was set within a deeply rooted sense of ethical and aesthetic ‘right behaviour’ (as well as a strongly hierarchical community structure which held potential excess in check, and understood, in a highly sophisticated way, the need to balance creative self-expression with collective interaction and mutual support).

In the African and African-American context, the dancer who goes into trance is always being controlled in some sense by a divinity or spirits, so there is an element of ritual theatre which contains the fragility of the individual ego.

Similarly, at celebrations, no dancer hogs the floor for longer than a minute or two, reaching a brief climax, but not prolonging the transcendent thrill of near-ecstatic movement and expression beyond what is in some way ‘safe’ or acceptable in terms of strictly personal as opposed to collective expression.

Upon reading this I was powerfully struck by the concept of a community holding an artist safe while he or she explores the wilder reaches of individual expression. As Kidel goes on to argue, the absence of this protective tradition around Western rock music can be seen in the likes of Jimi Hendrix and Jim Morrison, who in the context of a culture entranced by individualism, found their lives overwhelmed and consumed by the awesome powers unrestrained artistic expression can unleash.

But these ideas have a far wider application. Rock music has merely reflected western philosophy and culture in its deification of the individual. When existentialism announced that ‘existence precedes essence’ – that we simply exist, and that any meaning we might then attribute to this ‘blank slate’ existence is solely created by ourselves and our own choices – we assumed that the ‘we’ in question must be our individual selves.

Our culture has moved further and further away from any sense of the collective, let alone concepts like oneness with Nature, or with all of creation, or even (Science forbid) God.

And it is this philosophy of ‘individualist existentialism’ – deeply embedded in our culture – that leads to the pervasive story that while some might find their meaning and fulfillment in trying to assure the future of endangered species, or disadvantaged humans, or even life itself, others may find theirs in greed, gluttony and destructiveness. For the true believer, there is no contradiction here because there is no underlying meaning to seek – only individual constructs.

Within the tenets of Western philosophy it appears a logically unassailable position given that everything is fundamentally meaningless and the freedom of the individual is simply self-evident, what possible reason could there be to cease doing whatever I may fancy?

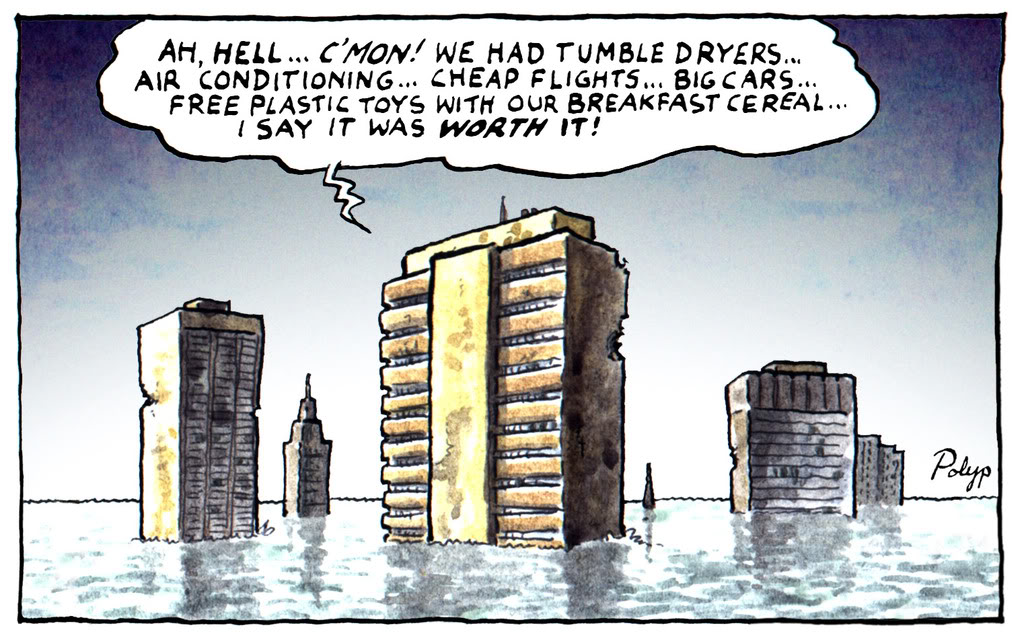

There seem to me to be two key answers to this question. The first is consequences. What I fancy now may not produce what I fancy tomorrow. If I choose to attach meaning or desirability to a reliable electricity supply, or food supply, then there are certain things I should really pay attention to.

But the second is empathy. While we may feel less empathy with beings more different or distant from ourselves, few of us would claim to feel no empathy at all. There is perhaps a sliding scale from total individualism to the sense of oneness with everything that is described in many of the Eastern mystical traditions, as well as among earlier representatives of the Abrahamic religions like Christianity. It is no coincidence that we tend to find individualists despoiling our common environment and those at the holistic end of the scale defending it.

Existentialist individualism argues that one’s position on this scale is a fundamentally meaningless personal decision. Our innate sense of empathy might whisper otherwise, but our scientific understanding of collective consequences like climate change forces us to recognise that even if individual freedom is our sole aim, we still have to change course, as the consequences of our actions will seriously curtail the future choices facing both ourselves and the rest of life on Earth.

Viewed from this perspective, climate change represents the death of passive individualism as a coherent philosophy.

So when Kidel speaks of the highly sophisticated understanding African cultures have of “the need to balance creative self-expression with collective interaction and mutual support”, he is not just talking about a better way to dance, he is speaking of the very cultural wisdom we need to build the future we deserve.

–

An extended version of this piece was first published on Dark Optimism in 2008, with this abridged version first appearing in The Future We Deserve in 2012.