by Shaun Chamberlin | Jun 9, 2010 | All Posts, Climate Change, Cultural stories, Favourite posts, Peak Oil, TEQs (Tradable Energy Quotas), The Transition Timeline, Transition Movement

https://www.darkoptimism.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/10-03-26-Radio-EcoShock_Chamberlin_LoFi.mp3 Christopher Fraser of London Transition has kindly transcribed the above popular interview with Canada’s Radio Ecoshock that I posted a couple of months back....

by Shaun Chamberlin | Mar 28, 2010 | All Posts, Climate Change, Cultural stories, Peak Oil, TEQs (Tradable Energy Quotas), The Transition Timeline, Transition Movement

https://www.darkoptimism.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/10-03-26-Radio-EcoShock_Chamberlin_LoFi.mp3 Above is a 24 minute interview I did last week with Canada’s excellent Radio Ecoshock. The full 60 minute show can be heard here. Dark Optimism readers may also...

by Shaun Chamberlin | Mar 15, 2010 | All Posts, Cultural stories, Peak Oil, Politics, Reviews and recommendations, TEQs (Tradable Energy Quotas)

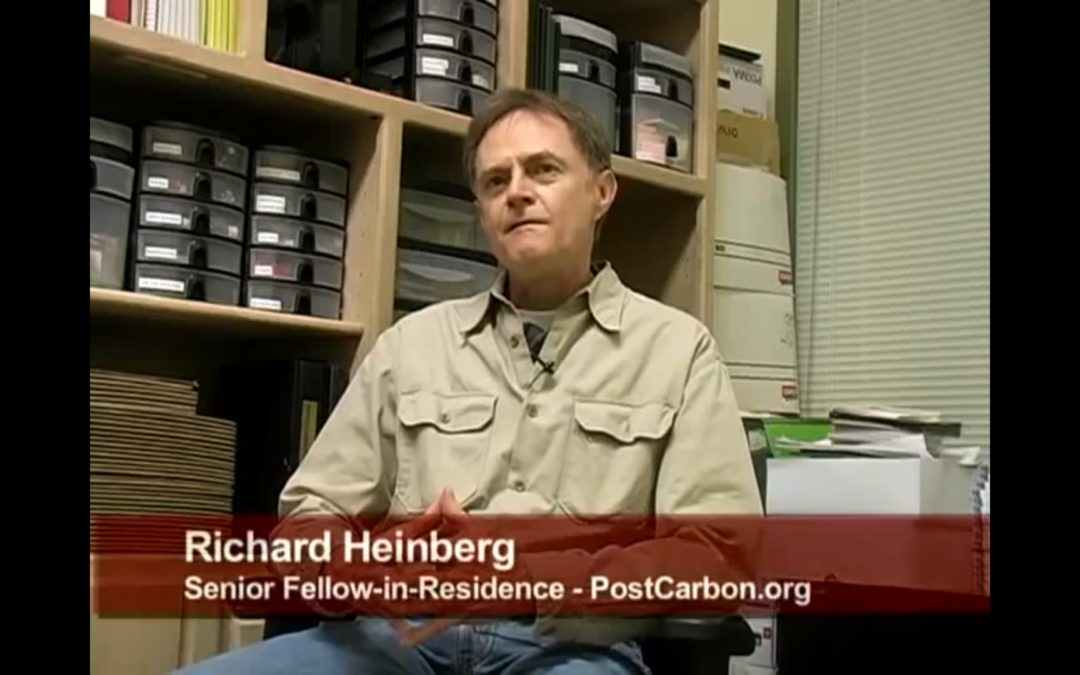

See below for an interview with the ever-insightful Richard Heinberg, discussing where we should put our efforts in the aftermath of the failure of the Copenhagen climate summit. It is well worth a watch, and you might want to consider spreading it to your contacts...

by Shaun Chamberlin | Feb 23, 2010 | All Posts, Cultural stories, Favourite posts, Peak Oil, Philosophy, The Transition Timeline

Below the cut is the text of my latest article for the highly-recommended Resurgence magazine. They asked me to tell the story of my own personal journey thus far, and how I ended up doing what I do. Thanks to Resurgence for permission to reproduce it here (and on my...

by Shaun Chamberlin | Dec 7, 2009 | All Posts, Climate Change, Favourite posts, Peak Oil

The above ‘Carbon IQ test’ is an excellent way of exploring how much you know about the carbon cycle, and what that means for viable solutions to our climate challenge. Have a go at it before checking out the information...

by Shaun Chamberlin | Aug 14, 2009 | All Posts, Climate Change, Cultural stories, Favourite posts, Peak Oil, Politics, TEQs (Tradable Energy Quotas)

As the evidence for the utter inapplicability of free market carbon trading to our climate emergency continues to pile up, interest continues to grow in the less PR-friendly alternative — the rationing of carbon-rated energy. Yesterday, the UK Government’s All...

Recent Comments