by Shaun Chamberlin | Jan 18, 2019 | 21st December, All Posts, Cultural stories, David Fleming, Economics, Favourite posts, Featured, Lean Logic, Surviving the Future, The Sequel

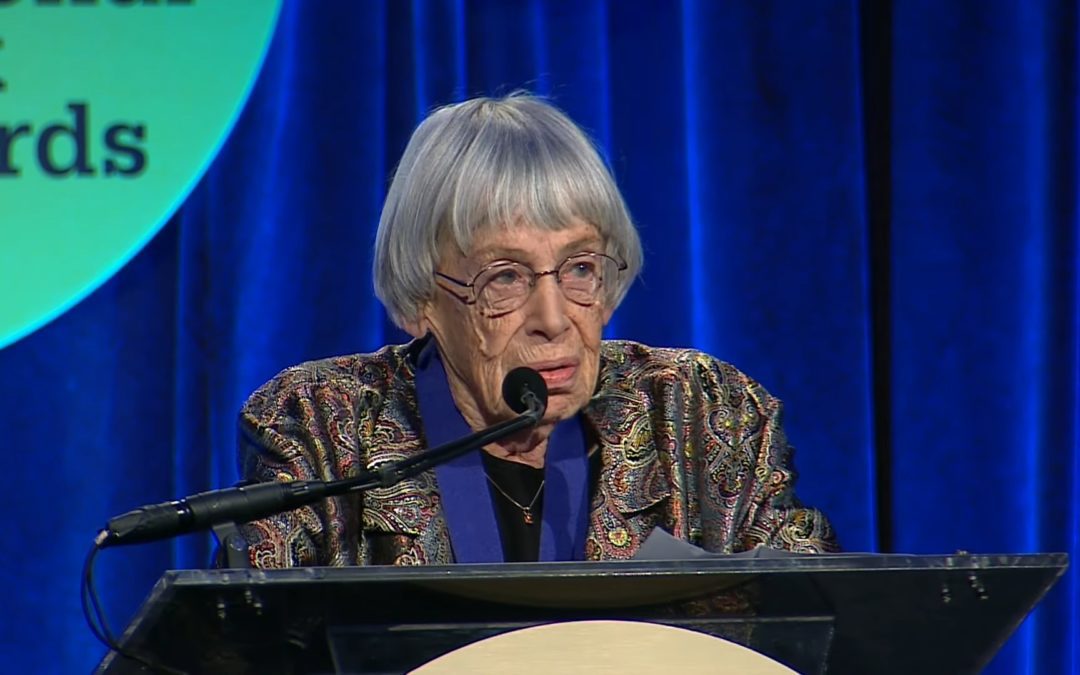

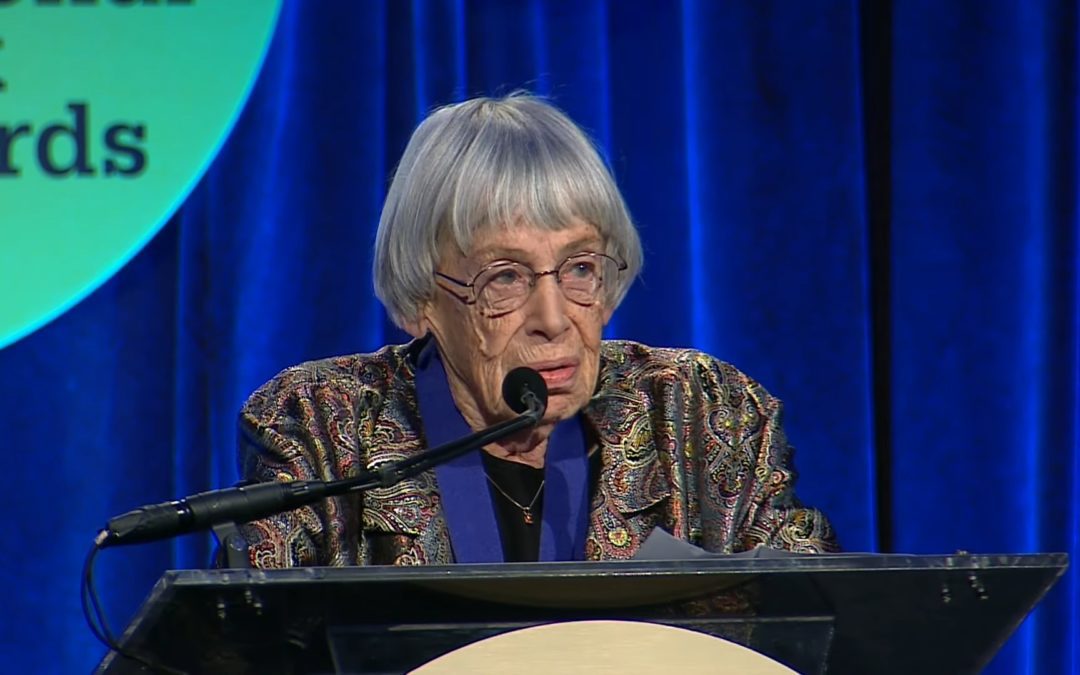

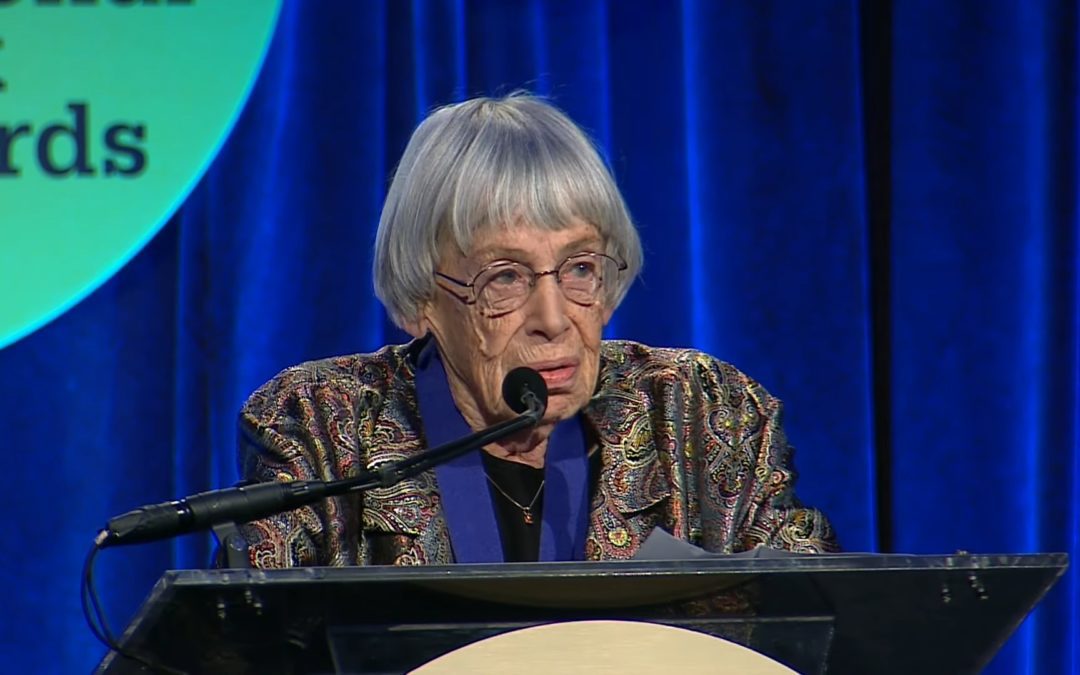

In 2014 Ursula K. Le Guin accepted the Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters with a deliciously powerful speech.

Aware that her time was nearing its end, she declared that her “beautiful reward” was accepted on behalf of, and shared with...

by Shaun Chamberlin | Dec 21, 2014 | 21st December, All Posts, Climate Change, Cultural stories, Favourite posts, Out and about, Philosophy

This is an excerpt from a longer video interview Rhonda Fabian conducted with Shaun Chamberlin at the opening of the New Story Summit in Findhorn, Scotland. Part of a Findhorn Foundation documentary initiative. Transcript originally published in the Kosmos Journal....

by Shaun Chamberlin | Dec 21, 2012 | 21st December, All Posts, Climate Change, Cultural stories, Favourite posts, Philosophy, Transition Movement

Let me tell you a story. It’s a story about our land — our home — and our ability to live peaceful, harmonious, respectful lives upon it and in partnership with it. And it’s a story about the big bad political structures and corporate institutions that conspire to...

by Shaun Chamberlin | Dec 21, 2011 | 21st December, All Posts, Cultural stories, Reviews and recommendations

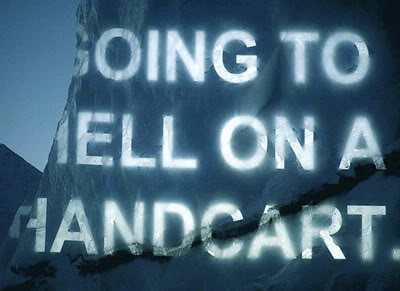

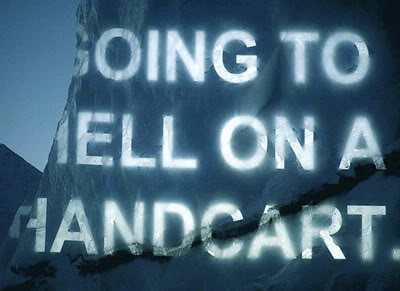

David Buckland, text Amy Balkin, ‘Going to hell on a handcart.’, Ice Art “Untitled, 2010” was written by artist Maria Elvorith for The Future We Deserve, a book project about collaboratively creating the future we deserve, set for publication in January...

Recent Comments