by Shaun Chamberlin | Nov 5, 2011 | All Posts, Climate Change, Cultural stories, Economics, Favourite posts, Peak Oil, Politics, Transition Movement

This post was written for the Transition Network's Social Reporting project, and published there on Sunday 13th November.

---

Having been invited to be this week's Social Reporting guest editor and introduce the theme of economics, the burgeoning 'Occupy' movement seemed the obvious place to start.

Over the last couple of months I have been fascinated as the occupations started with OccupyWallStreet on Sept 17th, followed by others joining in solidarity around the world, including OccupyLondon, which has been the London Stock Exchange's new neighbour since Oct 15th.

I've not been well lately, so haven't been able to be there as much as I'd like, but I have been following events closely online and visiting when I can. It has been interesting to note that most of those I have met at OccupyLondon hadn't previously heard of Transition, and that got me thinking about the parallels and differences between the two movements...

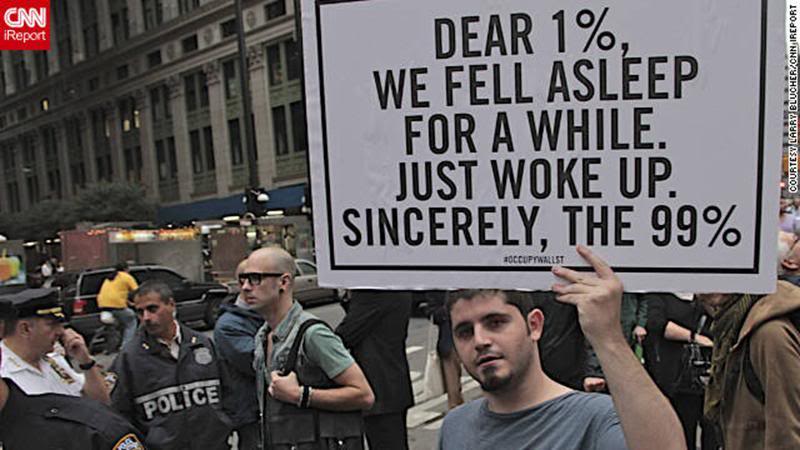

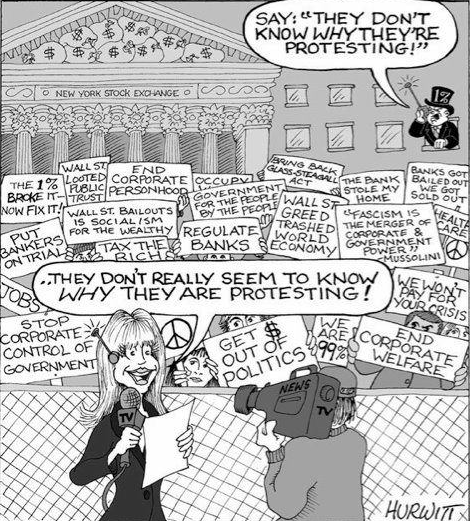

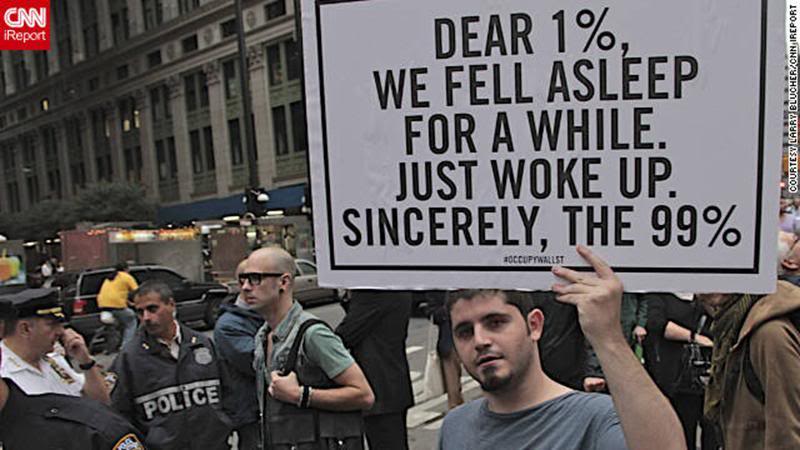

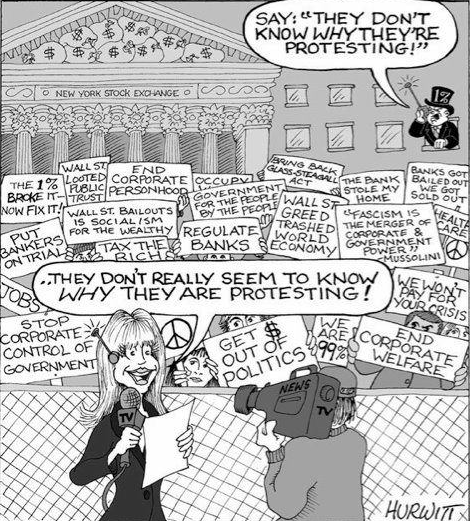

So what is 'Occupy' all about? A lot has been made in the mainstream media about the elusive "one demand" that Adbusters referred to in the original image that sparked the movement, and the ensuing lack of a single clear demand to fulfil that call.

And yet the basic point comes through loud and clear. Our economic system is profoundly unfair, and we want profound change. We live under a system in which banks receive more in subsidies than they pay in taxes, where they use their power to actually create money out of thin air, where they receive hundreds of billions in bailouts, and where the graph of global income distribution looks, well, like this:

And yet the basic point comes through loud and clear. Our economic system is profoundly unfair, and we want profound change. We live under a system in which banks receive more in subsidies than they pay in taxes, where they use their power to actually create money out of thin air, where they receive hundreds of billions in bailouts, and where the graph of global income distribution looks, well, like this:

It is easy to see why 'the 99%' might have something to say to 'the 1%' (the spike on the right should actually continue upwards over ten thousand times as far as shown here, or more than a kilometre above your computer!), and it also easy for us to let our brains boggle at numbers in the hundreds of billions of pounds. What can such numbers really mean? Yet Occupy has learned the hard way that they can become terribly real when we see some of the things that this virtually unlimited money is used for.

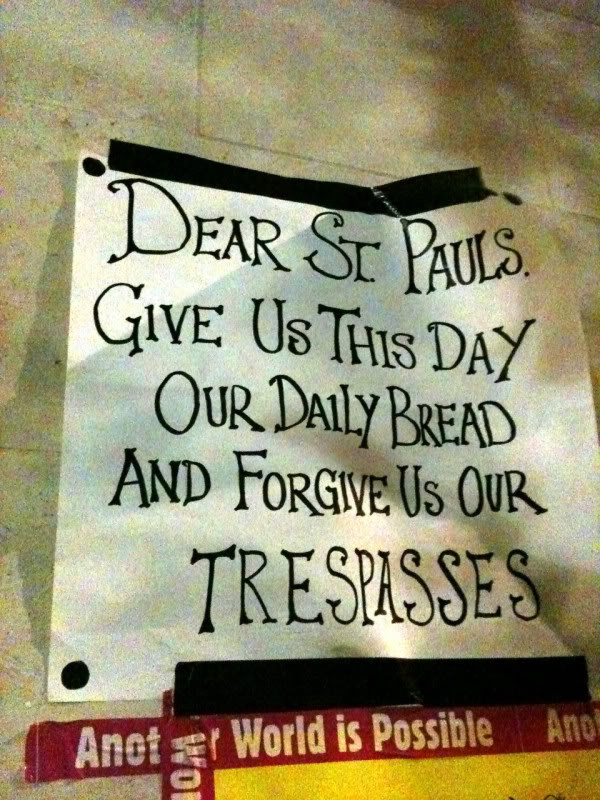

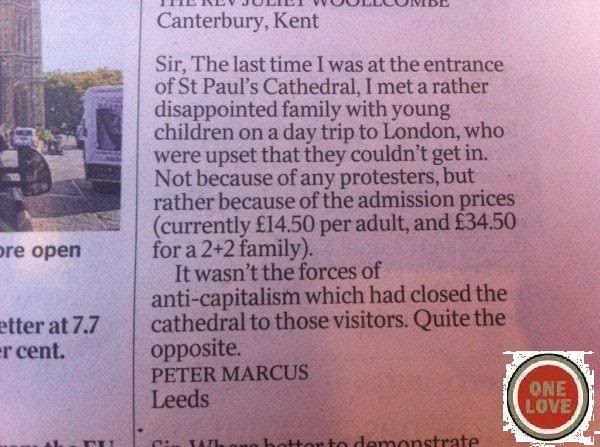

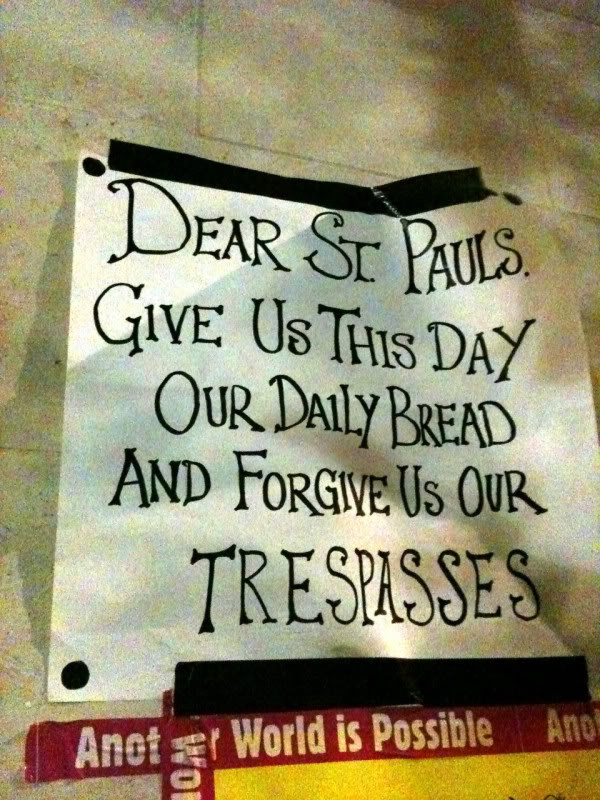

For example, the New York Police Department, which has been increasingly violent in its treatment of OccupyWallSt, was given a $4.6m donation by bailed-out Wall Street megabank JP Morgan Chase, and the New York Stock Exchange and Wall Street corporations apparently now actually hire individual serving policemen for $37/hr. Such riches also permit the big financial institutions to appear generous by becoming the chief sponsors of organisations like St. Paul's Cathedral. Not to mention of course that more than 99% of us work for money, which is apparently being magicked out of thin air by others, who then use this free resource to pay the rest of us to do whatever they see fit.

It suddenly becomes crystal clear why the Oakland public were chanting "who are you protecting?" as the Oakland police force closed in to attack them for being in the streets of Oakland, threatening the use of "chemical agents" via a megaphone and throwing a flash grenade at those trying to help a wounded man:

Witnesses (AKA social reporters!) claim that one protester actually threw dollar bills at the police line while shouting "will you protect us now?" Incidentally, on the same day, on this side of the pond, Sky News were busy telling Occupy London campers that "what you're doing is imposing your will on everybody else in a similar way (to the Nazis)". Hm. Reasons abound for us to do our own reporting!

Now, at first glance, all this confrontation might seem a world away from working diligently to improve the resilience of our local communities, but I believe that the links are strong, and I hope to see them grow even stronger. Let me explain why.

Both Transition and Occupy are founded on a belief that the current economic system is leading us to a future that none of us desire and, although peak oil seems to be a new term to many of those at OccupyLondon, we also share a strong strand of concern over climate change.

The big question for OccupyLondon though is what next? Substantial public support has helped resist the attempts of the Church of England and Corporation of London to have them moved on, and with St. Paul's having conceded that the camp presents no reason for the Cathedral to close its doors, Occupy London has established a site, at least for now. But what to do with it?

It is easy to see why 'the 99%' might have something to say to 'the 1%' (the spike on the right should actually continue upwards over ten thousand times as far as shown here, or more than a kilometre above your computer!), and it also easy for us to let our brains boggle at numbers in the hundreds of billions of pounds. What can such numbers really mean? Yet Occupy has learned the hard way that they can become terribly real when we see some of the things that this virtually unlimited money is used for.

For example, the New York Police Department, which has been increasingly violent in its treatment of OccupyWallSt, was given a $4.6m donation by bailed-out Wall Street megabank JP Morgan Chase, and the New York Stock Exchange and Wall Street corporations apparently now actually hire individual serving policemen for $37/hr. Such riches also permit the big financial institutions to appear generous by becoming the chief sponsors of organisations like St. Paul's Cathedral. Not to mention of course that more than 99% of us work for money, which is apparently being magicked out of thin air by others, who then use this free resource to pay the rest of us to do whatever they see fit.

It suddenly becomes crystal clear why the Oakland public were chanting "who are you protecting?" as the Oakland police force closed in to attack them for being in the streets of Oakland, threatening the use of "chemical agents" via a megaphone and throwing a flash grenade at those trying to help a wounded man:

Witnesses (AKA social reporters!) claim that one protester actually threw dollar bills at the police line while shouting "will you protect us now?" Incidentally, on the same day, on this side of the pond, Sky News were busy telling Occupy London campers that "what you're doing is imposing your will on everybody else in a similar way (to the Nazis)". Hm. Reasons abound for us to do our own reporting!

Now, at first glance, all this confrontation might seem a world away from working diligently to improve the resilience of our local communities, but I believe that the links are strong, and I hope to see them grow even stronger. Let me explain why.

Both Transition and Occupy are founded on a belief that the current economic system is leading us to a future that none of us desire and, although peak oil seems to be a new term to many of those at OccupyLondon, we also share a strong strand of concern over climate change.

The big question for OccupyLondon though is what next? Substantial public support has helped resist the attempts of the Church of England and Corporation of London to have them moved on, and with St. Paul's having conceded that the camp presents no reason for the Cathedral to close its doors, Occupy London has established a site, at least for now. But what to do with it?

The mainstream media have been clamouring for a list of demands, yet I and many others find it refreshing that none has yet been forthcoming.

I fear that setting demands is tantamount to saying "give us this much and then we will go home and allow the destruction that is business as usual to continue". For example, there is growing momentum behind calls for Occupy to demand a 'Robin Hood tax'. Yet as banks can and do create money it seems that demanding a fraction back might amount to selling ourselves for nothing.

The mainstream media have been clamouring for a list of demands, yet I and many others find it refreshing that none has yet been forthcoming.

I fear that setting demands is tantamount to saying "give us this much and then we will go home and allow the destruction that is business as usual to continue". For example, there is growing momentum behind calls for Occupy to demand a 'Robin Hood tax'. Yet as banks can and do create money it seems that demanding a fraction back might amount to selling ourselves for nothing.

"There is always an easy solution to every human problem — neat, plausible, and wrong" ~ H. L. Mencken

Given the mess things are in, it seems absurd to expect a simple set of demands that could put it all right. Instead, OccupyLondon has as yet adopted what seems to me a far more mature approach - setting up teach-ins and a 'university' in which we can educate ourselves, and then giving the resultant discussions as long as they need. It says to the guardians of the status quo "Ok, no, we don't have all the answers, but it's abundantly clear that you don't either, so let's talk it over."

And it's here where I fancy Transitioners might have a few things to say (as well as much to learn!) with our growing experience of building local economic networks that make a lot more sense than this globalised mess:

The first thing that I think Transitioners can usefully contribute to the discussions is an awareness of the energy limits that we are facing, and what they mean for the possibility of continued economic growth (even leaving aside the question of its desirability). If Occupy became just a mass demand for the politicians to roll back the cuts and rescue those who have been abandoned, it might be set to fail, because the era of increasing energy abundance is over, whatever politicians might say or do.

On the other hand, if Occupy recognises the inherent problem of protesting against the system your lifestyle depends upon, then the conversation goes to a much more interesting place - can we build alternative, independent systems to support us, even in a period of energy descent? This is where Transition's five years of experience might be most helpful.

As Sharon Astyk put it:

"The reality is that the growth we've lived with is going away whether we like it or not - I'm hoping that this new emergent consensus that we've been screwed comes with a collective response to the end of growth - or the solidarity won't last as the system pits people against one another"

So on that note, I hand over to the social reporters to explore this week's topic of Transition economics. From local e-currencies to the gift economy - what can we bring to the discussion that is sweeping the world?

Blogs posted in response by other Transitioners:

The local Heathrow economy - Nov 14, 2011

Ye are many - they are few - Nov 15, 2011

just another brick in the wall (street) - Nov 15, 2011

Our Money Our Future - Money for the 99% by the 99% - Nov 17, 2011

Time to Get to Work - Nov 18, 2011

We Can't Eat Money - Nov 19, 2011

--

Edit - On Nov 9, Rob Hopkins and I did a joint presentation on Transition at OccupyLondon. Rob's report, including an interview with me, can be found here.

Blogs posted in response by other Transitioners:

The local Heathrow economy - Nov 14, 2011

Ye are many - they are few - Nov 15, 2011

just another brick in the wall (street) - Nov 15, 2011

Our Money Our Future - Money for the 99% by the 99% - Nov 17, 2011

Time to Get to Work - Nov 18, 2011

We Can't Eat Money - Nov 19, 2011

--

Edit - On Nov 9, Rob Hopkins and I did a joint presentation on Transition at OccupyLondon. Rob's report, including an interview with me, can be found here.

by Shaun Chamberlin | Jul 25, 2011 | All Posts, Cultural stories, Economics, Favourite posts, Politics, Reviews and recommendations

I recently heard an interviewer ask someone who their heroes are, and was struck by the lack of names that came up when I asked myself the same question (although Dr. James Hansen now springs to mind...)

But now I think I have one, having discovered the brave story of Robin Bank (AKA Enric Duran). He is a Catalan activist who spent the two years to 2008 taking out loans totalling nearly half a million euros, and then donated all of the money to various social movements working to build alternatives to our unequal and suicidal economic-political system. His video message revealing what he had done and explaining his motives is posted above. I consider it one of the most inspiring stories of insight and resultant action that I have yet heard.

by Shaun Chamberlin | Mar 30, 2011 | All Posts, Climate Change, Cultural stories, Favourite posts, Politics, Reviews and recommendations

Robert Foster's brilliant Rap News makes it onto Dark Optimism for the second time, with a comment on recent events featuring the likes of Hugo Chavez, Glenn Beck, Bono ("Tell China to end first world debt") and John Pilger, as well as footage from the ongoing American revolution.

Well worth a watch, as is this interview, where Noam Chomsky dismantles Jeremy Paxman's worldview to his face.

Edit - 28/04/11 - And here's a sincere call for American revolution, from Adbusters.

by Shaun Chamberlin | Jan 23, 2011 | All Posts, Climate Change, Cultural stories, Economics, Peak Oil, Politics, Reviews and recommendations, TEQs (Tradable Energy Quotas), Transition Movement

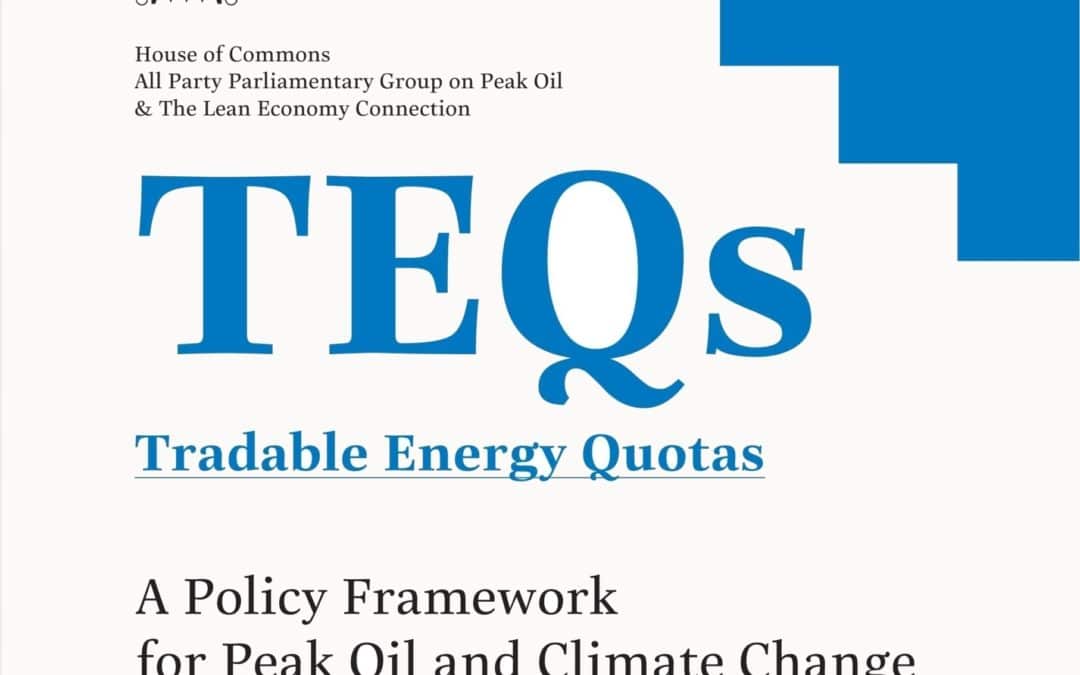

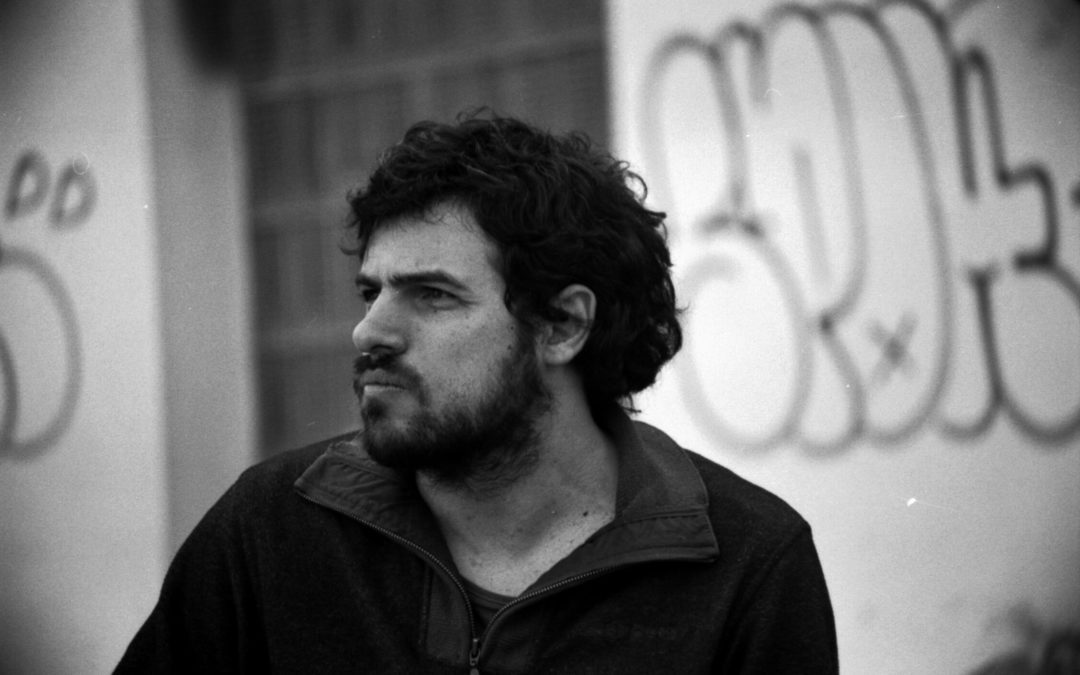

What a week - Tuesday's launch of the All Party Parliamentary Group on Peak Oil's report into TEQs was a tremendous success, with excellent media coverage, including Time magazine, The Sunday Times, Bloomberg News, the BBC, the Financial Times and many others (linked article list). The only problem has been that the degree of interest has been such that I haven't found a moment to write anything here - although I have been Tweeting, I feel as though I'm the last to cover it!

A fuller, more thoughtful piece may follow when time allows, but for now take a look at the videos from the event (Caroline Lucas MP, John Hemming MP, Jeremy Leggett and me), the various blogs that are discussing the implications, and of course the report itself.

On a personal note, it has been hard getting through all this without my co-author David Fleming, who passed away suddenly around six weeks ago (I also suffered another extremely close bereavement shortly after), but I am pleased and proud that it has gone so well. Many people have worked to make it possible and given their support, but I'd particularly like to thank Beth Stratford, an inspiring climate campaigner and the editor of the report, who over the past few weeks has given more time than she really had to help make the launch a success. Thanks Beth.

by Shaun Chamberlin | Sep 29, 2010 | All Posts, Cultural stories, Favourite posts, Philosophy, Politics, Reviews and recommendations

I have just spent an intrigued couple of hours musing over the outstanding new Common Cause report, which explores the battle over cultural values that underlies communications and marketing, while keeping one eye always on our environmental challenges.

The report has both stimulated a fair bit of controversy (as I will explore below the cut) and, excitingly, provided an answer to a question that has been bothering me for many years now, since reading Edward Bernays' influential 1928 book Propaganda.

(full text available online here or here)

First, then, a little history. Bernays was the nephew of Sigmund Freud, and the pioneer founder of the industry now termed "Public Relations" (the "Propaganda" name being discarded due to associations with the German war effort). Building on his uncle's ideas about subconscious urges and desires that drive our decisions, Bernays argued that:

"The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society… We are governed, our minds are moulded, our tastes formed, our ideas suggested, largely by men we have never heard of. This is a logical result of the way in which our democratic society is organized. Vast numbers of human beings must cooperate in this manner if they are to live together as a smoothly functioning society...In almost every act of our daily lives...we are dominated by the relatively small number of persons...who understand the mental processes and social patterns of the masses."

To my mind this is pretty distasteful stuff, but it has undoubtedly proved a significant force in shaping the consumerist society around us. We may disapprove of the marketers, PR men and spin doctors invading our minds at every opportunity, but we cannot deny the power of the techniques Bernays developed.

(full text available online here or here)

First, then, a little history. Bernays was the nephew of Sigmund Freud, and the pioneer founder of the industry now termed "Public Relations" (the "Propaganda" name being discarded due to associations with the German war effort). Building on his uncle's ideas about subconscious urges and desires that drive our decisions, Bernays argued that:

"The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society… We are governed, our minds are moulded, our tastes formed, our ideas suggested, largely by men we have never heard of. This is a logical result of the way in which our democratic society is organized. Vast numbers of human beings must cooperate in this manner if they are to live together as a smoothly functioning society...In almost every act of our daily lives...we are dominated by the relatively small number of persons...who understand the mental processes and social patterns of the masses."

To my mind this is pretty distasteful stuff, but it has undoubtedly proved a significant force in shaping the consumerist society around us. We may disapprove of the marketers, PR men and spin doctors invading our minds at every opportunity, but we cannot deny the power of the techniques Bernays developed.

All of which brings us back to that uncomfortable question: given the urgency of the peril facing our biosphere, and the potency of this approach, is there a way to justify such manipulation for the sake of preserving a future for all (as indeed many are trying to do)?

On those terms, I have always leant towards the answer "no". But Common Cause offers a potential way to harness this potency without being manipulative: transparency.

By all means understand and utilise all the power inherent in your messaging, but be explicit about the values you are trying to promote, and explain why.

Like most important insights, this solution is simple yet powerful, for by this one act you not only bring integrity to your efforts to spread the values you believe in, but also simultaneously open up an important debate over the desirability of those values AND shine a light on the dubious morality of all those doing similar work from the cover of darkness.

For me, it is a great relief to see a niggling question laid to rest in such an elegant way, and I am grateful for it.

All of which brings us back to that uncomfortable question: given the urgency of the peril facing our biosphere, and the potency of this approach, is there a way to justify such manipulation for the sake of preserving a future for all (as indeed many are trying to do)?

On those terms, I have always leant towards the answer "no". But Common Cause offers a potential way to harness this potency without being manipulative: transparency.

By all means understand and utilise all the power inherent in your messaging, but be explicit about the values you are trying to promote, and explain why.

Like most important insights, this solution is simple yet powerful, for by this one act you not only bring integrity to your efforts to spread the values you believe in, but also simultaneously open up an important debate over the desirability of those values AND shine a light on the dubious morality of all those doing similar work from the cover of darkness.

For me, it is a great relief to see a niggling question laid to rest in such an elegant way, and I am grateful for it.

Yet in reading around the report, I discovered that others, such as Solitaire Townsend of Futerra, disagree, and forcefully so. She writes:

"The notion of changing the audience rather than the message is at the heart of (this) concept. It argues that we shouldn’t accept the basic psychology of our audience – but seek to change it.

This means re-programming people’s values away from consumption, status and selfish desires and towards collective awareness and a closer relationship with our place in the natural world. Actually this drives us (at Futerra) bonkers, especially because implicit is the message ‘if only everyone else thought and acted like us everything would be okay’.

That makes our skin crawl a bit, and we know the majority public audience hates environmental worthies suggesting there’s not only something wrong with their footprint: there’s something wrong with their personality."

I have often felt myself recoil from Futerra's approach to "promoting sustainable development", and this helped me to put my finger on why.

As report author Tom Crompton pointed out in his response, all messaging changes the audience. While I agree with Solitaire that this fact is in some ways distasteful, for me the appropriate response to this distaste is not to pretend that one's own messaging is somehow exempt from having such influence, but rather to explore the reality behind this dangerous power, and to seek a way to use it in an honest and beneficial way.

Common Cause's radical transparency provides exactly that and, promisingly, the report is supported by five influential NGOs (including, incidentally, some that I have personally decided to stop supporting).

Yet in reading around the report, I discovered that others, such as Solitaire Townsend of Futerra, disagree, and forcefully so. She writes:

"The notion of changing the audience rather than the message is at the heart of (this) concept. It argues that we shouldn’t accept the basic psychology of our audience – but seek to change it.

This means re-programming people’s values away from consumption, status and selfish desires and towards collective awareness and a closer relationship with our place in the natural world. Actually this drives us (at Futerra) bonkers, especially because implicit is the message ‘if only everyone else thought and acted like us everything would be okay’.

That makes our skin crawl a bit, and we know the majority public audience hates environmental worthies suggesting there’s not only something wrong with their footprint: there’s something wrong with their personality."

I have often felt myself recoil from Futerra's approach to "promoting sustainable development", and this helped me to put my finger on why.

As report author Tom Crompton pointed out in his response, all messaging changes the audience. While I agree with Solitaire that this fact is in some ways distasteful, for me the appropriate response to this distaste is not to pretend that one's own messaging is somehow exempt from having such influence, but rather to explore the reality behind this dangerous power, and to seek a way to use it in an honest and beneficial way.

Common Cause's radical transparency provides exactly that and, promisingly, the report is supported by five influential NGOs (including, incidentally, some that I have personally decided to stop supporting).

But I think there is a wider issue rearing its head here too; a logical flaw that underpins much modern discussion, especially when it comes to our environmental challenges.

When Solitaire goes on to argue that "we don't have time for a cultural shift" and so that we must engage with people where they're at, her argument is that approach A can't possibly work, so we must try approach B.

We see the same form of argument all over the place. Renewables can't scale up quickly enough to replace fossil fuels so we must have nuclear power. The Conservatives and Liberal Democrats aren't running the country well, so we must vote Labour. And on and on.

But the premisses and the conclusion do not join up. Even if we accept that A doesn't work, it doesn't necessarily mean that B will. Indeed, B could be far far worse, this argument just doesn't tell us. This much is evident at a glance, yet still this form of argument is everywhere, and generally treated with respect.

The alternative is to face the possibility that maybe none of the options presented are satisfactory. Maybe we truly don't have time for a cultural revolution AND 'ethical consumerism' truly can't save the world. Maybe neither renewables NOR nuclear can sustain a consumerist society over the coming decades. And so on...

It is when we explore this space - when we consider the evidence on all the propositions, rather than assuming that the last remaining option simply MUST work - that we start to consider reality, and thus open the door to true creativity.

But I think there is a wider issue rearing its head here too; a logical flaw that underpins much modern discussion, especially when it comes to our environmental challenges.

When Solitaire goes on to argue that "we don't have time for a cultural shift" and so that we must engage with people where they're at, her argument is that approach A can't possibly work, so we must try approach B.

We see the same form of argument all over the place. Renewables can't scale up quickly enough to replace fossil fuels so we must have nuclear power. The Conservatives and Liberal Democrats aren't running the country well, so we must vote Labour. And on and on.

But the premisses and the conclusion do not join up. Even if we accept that A doesn't work, it doesn't necessarily mean that B will. Indeed, B could be far far worse, this argument just doesn't tell us. This much is evident at a glance, yet still this form of argument is everywhere, and generally treated with respect.

The alternative is to face the possibility that maybe none of the options presented are satisfactory. Maybe we truly don't have time for a cultural revolution AND 'ethical consumerism' truly can't save the world. Maybe neither renewables NOR nuclear can sustain a consumerist society over the coming decades. And so on...

It is when we explore this space - when we consider the evidence on all the propositions, rather than assuming that the last remaining option simply MUST work - that we start to consider reality, and thus open the door to true creativity.

Perhaps none of the mainstream parties are satisfactory, so I should support a smaller one, or not vote at all, or start my own, or work to change the political system, or...

Perhaps none of today's technologies can power a consumerist lifestyle for all the world's people, so we need to accept vast inequalities, or reduce our energy demand, or redefine our idea of a desirable lifestyle, or...

Let's not assume that the truth must always be found laid out among the presented options.

As I mentioned in response to comments on an earlier post, I believe that refusing to flee to quick, unexamined answers is one of our key strategies at this point in human history, as the limits of our current paradigms loom ever larger. We must explore new stories.

As Rilke so beautifully put it:

“Be patient toward all that is unsolved in your heart and try to love the questions themselves. Do not now seek the answers, which cannot be given you because you would not be able to live them. And the point is to live everything. Live your questions now, and perhaps even without knowing it, you will live along some distant day into your answers.”

Perhaps none of the mainstream parties are satisfactory, so I should support a smaller one, or not vote at all, or start my own, or work to change the political system, or...

Perhaps none of today's technologies can power a consumerist lifestyle for all the world's people, so we need to accept vast inequalities, or reduce our energy demand, or redefine our idea of a desirable lifestyle, or...

Let's not assume that the truth must always be found laid out among the presented options.

As I mentioned in response to comments on an earlier post, I believe that refusing to flee to quick, unexamined answers is one of our key strategies at this point in human history, as the limits of our current paradigms loom ever larger. We must explore new stories.

As Rilke so beautifully put it:

“Be patient toward all that is unsolved in your heart and try to love the questions themselves. Do not now seek the answers, which cannot be given you because you would not be able to live them. And the point is to live everything. Live your questions now, and perhaps even without knowing it, you will live along some distant day into your answers.”

by Shaun Chamberlin | Mar 15, 2010 | All Posts, Cultural stories, Peak Oil, Politics, Reviews and recommendations, TEQs (Tradable Energy Quotas)

See below for an interview with the ever-insightful Richard Heinberg, discussing where we should put our efforts in the aftermath of the failure of the Copenhagen climate summit. It is well worth a watch, and you might want to consider spreading it to your contacts via the "Share This" link in the bottom right corner of this post.

I heartily endorse his perspective, but disagree when he argues in support of carbon taxation at around fifteen minutes in, saying that "we need to make fossil fuels more expensive". In my opinion, we do not - we need to guarantee a fair entitlement to the available energy, not ration it by the depth of people's pockets.

As Richard says, "if you're taxing everybody on their use of fossil fuels - raising their cost of living - it's pretty hard to get their buy-in to that", but once you guarantee people a fair entitlement, in line with a declining cap, society can then collectively focus on keeping the price of energy as low as possible, which is a simply-understood task that everyone can buy into with enthusiasm.

Richard is touching on a widely-unrecognised contradiction at the heart of present energy/climate policy discussions - the desire to raise carbon prices while keeping energy prices low. Market-based approaches struggle to see past this, but TEQs would resolve it at a stroke, through the recognition that reducing the quantity of carbon emissions can be best achieved by means other than a high price.

And yet the basic point comes through loud and clear. Our economic system is profoundly unfair, and we want profound change. We live under a system in which banks receive more in subsidies than they pay in taxes, where they use their power to actually create money out of thin air, where they receive hundreds of billions in bailouts, and where the graph of global income distribution looks, well, like this:

And yet the basic point comes through loud and clear. Our economic system is profoundly unfair, and we want profound change. We live under a system in which banks receive more in subsidies than they pay in taxes, where they use their power to actually create money out of thin air, where they receive hundreds of billions in bailouts, and where the graph of global income distribution looks, well, like this:

It is easy to see why 'the 99%' might have something to say to 'the 1%' (the spike on the right should actually continue upwards over ten thousand times as far as shown here, or more than a kilometre above your computer!), and it also easy for us to let our brains boggle at numbers in the hundreds of billions of pounds. What can such numbers really mean? Yet Occupy has learned the hard way that they can become terribly real when we see some of the things that this virtually unlimited money is used for.

For example, the New York Police Department, which has been increasingly violent in its treatment of OccupyWallSt, was given a $4.6m donation by bailed-out Wall Street megabank JP Morgan Chase, and the New York Stock Exchange and Wall Street corporations apparently now actually hire individual serving policemen for $37/hr. Such riches also permit the big financial institutions to appear generous by becoming the chief sponsors of organisations like St. Paul's Cathedral. Not to mention of course that more than 99% of us work for money, which is apparently being magicked out of thin air by others, who then use this free resource to pay the rest of us to do whatever they see fit.

It suddenly becomes crystal clear why the Oakland public were chanting "who are you protecting?" as the Oakland police force closed in to attack them for being in the streets of Oakland, threatening the use of "chemical agents" via a megaphone and throwing a flash grenade at those trying to help a wounded man:

It is easy to see why 'the 99%' might have something to say to 'the 1%' (the spike on the right should actually continue upwards over ten thousand times as far as shown here, or more than a kilometre above your computer!), and it also easy for us to let our brains boggle at numbers in the hundreds of billions of pounds. What can such numbers really mean? Yet Occupy has learned the hard way that they can become terribly real when we see some of the things that this virtually unlimited money is used for.

For example, the New York Police Department, which has been increasingly violent in its treatment of OccupyWallSt, was given a $4.6m donation by bailed-out Wall Street megabank JP Morgan Chase, and the New York Stock Exchange and Wall Street corporations apparently now actually hire individual serving policemen for $37/hr. Such riches also permit the big financial institutions to appear generous by becoming the chief sponsors of organisations like St. Paul's Cathedral. Not to mention of course that more than 99% of us work for money, which is apparently being magicked out of thin air by others, who then use this free resource to pay the rest of us to do whatever they see fit.

It suddenly becomes crystal clear why the Oakland public were chanting "who are you protecting?" as the Oakland police force closed in to attack them for being in the streets of Oakland, threatening the use of "chemical agents" via a megaphone and throwing a flash grenade at those trying to help a wounded man:

The mainstream media have been clamouring for a list of demands, yet I and many others find it refreshing that none has yet been forthcoming.

I fear that setting demands is tantamount to saying "give us this much and then we will go home and allow the destruction that is business as usual to continue". For example, there is growing momentum behind calls for Occupy to demand a 'Robin Hood tax'. Yet as banks can and do create money it seems that demanding a fraction back might amount to selling ourselves for nothing.

The mainstream media have been clamouring for a list of demands, yet I and many others find it refreshing that none has yet been forthcoming.

I fear that setting demands is tantamount to saying "give us this much and then we will go home and allow the destruction that is business as usual to continue". For example, there is growing momentum behind calls for Occupy to demand a 'Robin Hood tax'. Yet as banks can and do create money it seems that demanding a fraction back might amount to selling ourselves for nothing.

All of which brings us back to that uncomfortable question: given the urgency of the peril facing our biosphere, and the potency of this approach, is there a way to justify such manipulation for the sake of preserving a future for all (

All of which brings us back to that uncomfortable question: given the urgency of the peril facing our biosphere, and the potency of this approach, is there a way to justify such manipulation for the sake of preserving a future for all (

But I think there is a wider issue rearing its head here too; a logical flaw that underpins much modern discussion, especially when it comes to our environmental challenges.

When Solitaire goes on to argue that "we don't have time for a cultural shift" and so that we must engage with people where they're at, her argument is that approach A can't possibly work, so we must try approach B.

We see the same form of argument all over the place. Renewables can't scale up quickly enough to replace fossil fuels so we must have nuclear power. The Conservatives and Liberal Democrats aren't running the country well, so we must vote Labour. And on and on.

But the premisses and the conclusion do not join up. Even if we accept that A doesn't work, it doesn't necessarily mean that B will. Indeed, B could be far far worse, this argument just doesn't tell us. This much is evident at a glance, yet still this form of argument is everywhere, and generally treated with respect.

The alternative is to face the possibility that maybe none of the options presented are satisfactory. Maybe we truly don't have time for a cultural revolution AND '

But I think there is a wider issue rearing its head here too; a logical flaw that underpins much modern discussion, especially when it comes to our environmental challenges.

When Solitaire goes on to argue that "we don't have time for a cultural shift" and so that we must engage with people where they're at, her argument is that approach A can't possibly work, so we must try approach B.

We see the same form of argument all over the place. Renewables can't scale up quickly enough to replace fossil fuels so we must have nuclear power. The Conservatives and Liberal Democrats aren't running the country well, so we must vote Labour. And on and on.

But the premisses and the conclusion do not join up. Even if we accept that A doesn't work, it doesn't necessarily mean that B will. Indeed, B could be far far worse, this argument just doesn't tell us. This much is evident at a glance, yet still this form of argument is everywhere, and generally treated with respect.

The alternative is to face the possibility that maybe none of the options presented are satisfactory. Maybe we truly don't have time for a cultural revolution AND '

Recent Comments